My recent deep dive into the Smith County Jail system left me better informed yet mulling over more complex issues. One repeated issue in my original research and interviews concerned bail. Without exception, the county officials I spoke with mentioned the inmates’ inability to afford bail as contributing to a consistently high jail population. Why is bail unaffordable for so many inmates in our jail? What is the cost of bail to the inmates, the county and our community? What efforts are being made to reform bail practices? Here’s what we do know.

During a Smith County Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee (CJCC) meeting in May 2018,114th District Court Judge Christi Kennedy, who has since retired from the bench, called bail reform “probably the hottest topic in criminal justice right now.” That was an accurate statement then and now. In my first of a three-part series on bail, a bit of history might be helpful to better understand the controversy surrounding bail and bail reform issues.

Origins of bail

Clay tablets found in modern day Iraq and dated ca. 2750 BC offer early evidence of surety bail bond agreements. Our modern money bail system had its beginnings in England between 410 and 1066 AD.

Surety was intended to settle disputes peacefully. The accused were tasked with finding providers to pay the agreed upon amount to the victim, should the accused flee. No money exchange was ever actually involved, only the assurance that the settlement could be paid if needed. In “Seeing Through the Emperor’s New Clothes: Rediscovery of Basic Principles in the Administration of Bail,” June Carbone said, “The Anglo-Saxon Bail process was perhaps the last entirely rational application of bail.”

That process remained for centuries, reworked and transplanted to the colonies and later the United States.

In the early 1900s, increased societal mobility meant greater opportunities for the accused to skip out before a trial or settlement and more absent or far-flung relatives, now unavailable for surety.

England passed the Bail Act in 1898 eliminating sureties and offering other methods of ensuring court appearances and preventing new crimes.

The face of bail in the U.S.

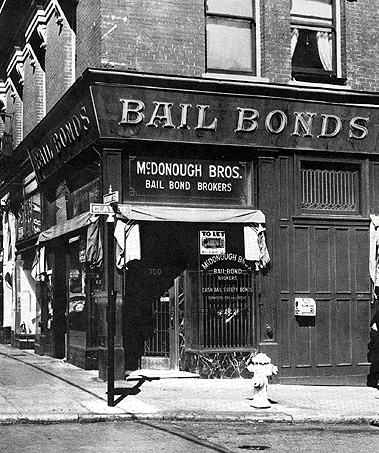

Conversely, the U.S. chose the opposite direction in 1896. Peter P. McDonough, a known underworld crime boss and saloon owner, established the first commercial bail bond business in San Francisco.

Over the century, the U.S. commercial bail bond business has morphed into a $2 billion industry. Notably, the U.S. and The Philippines are the only countries with a cash bail system dominated by commercial bail bondsmen.

During the 20th century, our bail system was the focus of much debate and reform measures. Under the Bail Reform Act of 1966, the first major revision of the bail system since the Judiciary Act of 1789, the accused were presumed entitled to release on personal recognizance or an uninsured appearance bond, although provisions were included for a monetary bond in cases considered a flight risk. Also, specific factors in setting bail were designed with the intent to assure appearance in court. Upon signing the act, President Lyndon Johnson remarked that the nature of the bill would “begin to ensure that defendants are considered as individuals – not as dollar signs.”

The Reform Act was a federal law and applied only to federal jurisdictions and Washington D.C. which together represent a minuscule portion of pretrial detainees. States remained free to design and operate under their individual bail administration systems.

A pivot forward in word but not in widespread practice

Although the Reform Act signaled a progressive step forward, monetary conditions remained in use resulting in widespread detention. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the decision-making process for setting bail tacitly considered the protection of public safety, even though public safety was not a focus of the Bail Reform Act of 1966, nor a historical function of bail.

With bail guidelines vague and inconsistent across jurisdictions, judges continued to exercise significant discretion in setting bail. Even with additional information such as work history, family and community ties available, judges preferred the traditional decision-making criteria – criminal charge, prior criminal record and indications of warrants or detainers outstanding – when determining bail.

During the 1970s and 1980s, “tough on crime” rhetoric and piecemeal legislation solidified with the Bail Reform Act of 1984, part of the Comprehensive Control Act. In codifying the right to detain for both flight risk and public safety consideration, the act expanded the categories of defendants who could be “preventively” detained.

In 1985, criminologist John Goldkamp described the problem as one in which “judges have conducted bail in a low-visibility, highly improvisational fashion with little meaningful guidance concerning how to transact bail to realize optimal results.”

Racial and economic discrimination compound poor bail outcomes

The “tough-on-crime” era ushered in decades of mass incarceration with rising jail and prison populations. Beginning in the 1980s, as incarceration rates rose, studies of bail outcomes showed that African American defendants had worse bail outcomes than white in similar situations, including higher bail amounts set for release. More recent studies have documented similar disparities in bail determination for Latino defendants.

These trends mounted nationally and continued to rise. As a result of discriminatory outcomes contributed to race, ethnicity and economic status, bail administration systems have come under considerable scrutiny during the last decade.

This history has culminated in the current movement for bail reform and increased bail reform litigation from diverse areas including California, Illinois, Arizona, New York and — nearest our area — Houston, Texas,

Part two of this series will explore the cost of bail — directly and indirectly — to individuals and communities.

Brenda McWilliams is retired after nearly 40 years in education and counseling. When not traveling she fills her days with community, charitable, and civic work; photography; writing and blogging at Pilgrim Seeker Heretic; reading, babysitting grandchildren, and visiting with friends. She enjoys walking at Rose Rudman or hiking at Tyler State Park. Brenda and her spouse, Lou Anne Smoot, the author of Out: A Courageous Woman’s Journey, have six children and seven grandchildren between them.

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.