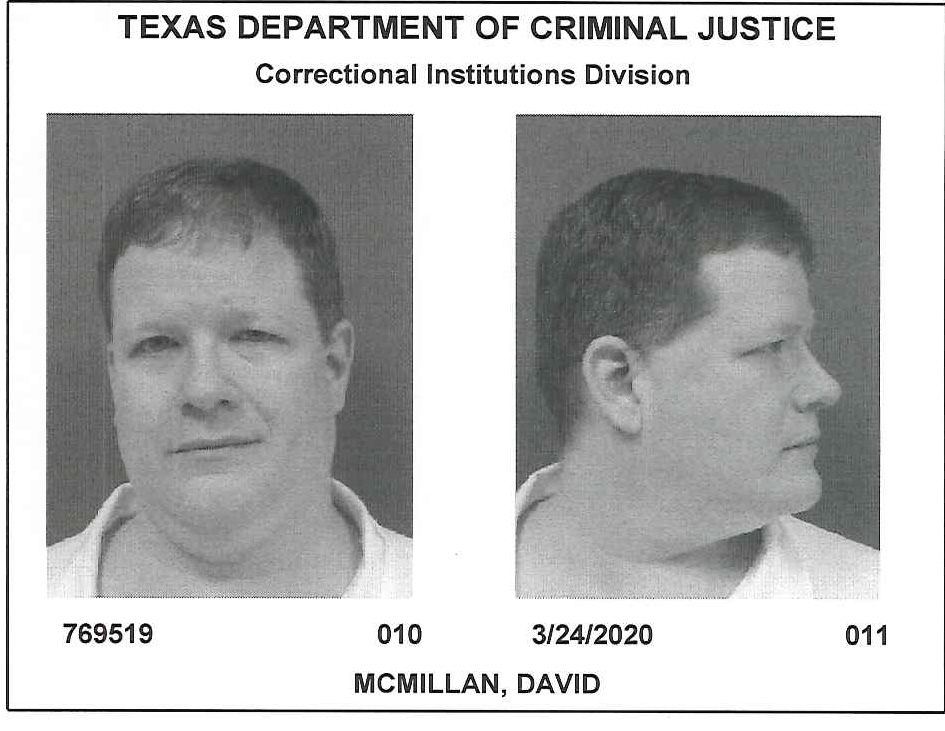

The words used to characterize David McMillan in 1996 weren’t flattering: goofy; impressionable; irresponsible; a pimple-faced geek who was more of a “follower” than a leader.

What the 17-year-old high school dropout saw reflecting in the mirror wasn’t much better.

“Poor, white trash,” the former Flint resident once wrote.

His immaturity, his age and the fact two co-defendants already had been sentenced to die for killing their victim, likely saved McMillan from his own capital murder conviction.

Instead, McMillan has spent the past 28 years behind bars serving a sentence the U.S. Supreme Court deemed unconstitutional.

He is one of a handful of Texas inmates the Texas Center for Justice and Equality argue should be given a second chance as a true measure of justice.

But something is missing from that ideal, especially when young offenders are involved, says Alycia Castillo, a justice center director. “Instead of rehabilitation or learning accountability, they are just receiving punishment,” she said. “Overall, that’s not a very productive process.”

Under the tough-on-crime mentality, juveniles who commit serious crimes should be treated as adults even if it means locking them up and throwing away the key. A majority of Supreme Court justices, however, deemed the latter cruel and unusual punishment.

Why? Because studies show mental ability to appreciate good judgment, assess risks and consequences and to control impulses doesn’t fully develop in adults until sometime in their mid 20s.

Adding abuse, neglect, peer pressure or the lack of power to escape harmful environments into the equation raises a serious question of culpability — and yet another question:

“Are young people who make mistakes irredeemable?” Castillo asked. “Our answer is no.”

A crime of hate

In a justice center writing project, McMillan said growing up he felt “clueless” about who he really was — unable, he said, “to get it all right.” He found acceptance in the “CB gang,” a loose-knit group that considered gay-bashing a hobby.

On the night of Nov. 30, 1993, McMillan and co-defendants Donald Aldrich, 29, and 19-year-old Henry Dunn cruised the streets around Tyler’s Bergfeld Park, one of the locations where younger members of the gay community were known to socialize. Aldrich, a charismatic leader who had served time for burglary and robbery, targeted a red Nissan pickup driven by a man he claimed had flirted with him.

Aldrich jumped into the passenger seat of the man’s vehicle. He later pulled a gun and ordered the driver, 23-year-old Nicholas West, into a separate vehicle occupied by Dunn and McMillan and led the group to a remote clay pit near Noonday. The three men then forced West out of the vehicle, marched him up a path, stripped him of his pants, punched him, shot him at least nine times and left him to die.

Impact

The gay community in Tyler seemed invisible until news of the murder spread nationwide, exposing a traditionally conservative community divided in fear — those who repressed their own sexuality and those who succumbed to homophobia.

“It was very difficult to be gay in the early 90s,” said Rob Jerger, who came out as gay about the time West was murdered. Jerger recalls being introduced to West but admits he didn’t know him well.

Separate jurors found Aldrich — who was tried in Kerrville — and Dunn — who was tried in Tyler — guilty of capital murder and recommended death sentences. Dunn was executed in 2003 and Aldrich in 2004.

Smith County prosecutors also charged McMillan with capital murder, claiming he promoted or assisted others in the slaying. They did not, however, seek the death penalty — a decision made, in part, by the lack of evidence showing McMillan actually caused West’s death. Although McMillan fired a shotgun that night, he missed hitting the victim.

Jurors in McMillan’s trial struggled for 12 hours over two days before rejecting the capital murder charge, instead convicting him of aggravated kidnapping and aggravated robbery.

McMillan received a life sentence but because the jury convicted him on the lesser charges, he would only have to serve 30 years instead of 40 before becoming eligible for parole. That window of opportunity opens within the next two years.

Catalyst for change

U.S. Supreme Court rulings the past 16 years reflect a renewed focus on punishment for juvenile offenders, especially those who receive sentences historically reserved for adults.

Citing the Eighth Amendment, the Roper v Simmons decision in 2005 banned executing offenders who were younger than 18 at the time they committed the offense, effectively commuting the sentence of 72 inmates in 12 states to life in prison.

Up until then, Texas led the country with inmates in this category – carrying out 13 of the 22 executions of juveniles since 1976, according to the Death Penalty Information Center based in Washington D.C.

The decision came too late for Napoleon Beazley who was just 3½ months away from his 18th birthday when he killed Tyler businessman John Luttig. Beazley was executed in 2002.

Subsequent rulings established that juveniles who receive a mandatory sentence of life without parole for homicide or life sentences for non-homicide convictions also violates the Constitution’s Eighth Amendment protecting against cruel and unusual punishment.

Juveniles may still be sentenced to discretionary life without parole in certain homicide cases but only after a full hearing to determine if the youth is permanently incorrigible or incapable of being rehabilitated.

Research of adolescent development provided the premise for this new approach in the juvenile justice system. In writing the majority opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy noted a child’s brain is not fully developed and does not have the same level of judgment or the ability to assess the consequences of their actions.

Juvenile justice reformists contend mitigating evidence concerning a juvenile offender’s maturity, background, particular family circumstances and probability of rehabilitation should be at least a part of considerations before sentencing.

Legislators in a number of states appear to agree. By 2012, 28 states had changed their laws involving punishment for juveniles convicted of homicide.

JLWOP

Today, about 2,500 juveniles remain incarcerated, serving life sentences without parole, a situation commonly referred to as JLWOP, according to information published by the Juvenile Law Center in Pennsylvania.

Challenging harsh sentences for juveniles tried as adults in the federal system often is a protracted process, especially if the person already has exhausted their direct appeals. Attorneys attempting to utilize the Supreme Court’s decisions can file a petition known as Habeas Corpus 2255 to challenge a sentence on grounds that it violates a person’s constitutional rights.

In 2013, Tyler attorney Deborah Race was appointed to pursue a commutation for a Marshall man who already has served 26 years of a 50-year sentence. She says Jermon Clark has defied the odds by becoming an “exceptional young man” while incarcerated — a record deserving of a second chance for a life outside of prison.

Clark had just turned 15 when on Nov. 25, 1993, he and two other juveniles — ages 16 and 17 — decided to steal a car and drive to California. The trio went to a Whataburger where one of the boys knew 16-year-old Susan Van Orden worked, and who had a car. When they asked her for a ride, she obliged. The situation soon turned sour when one of the boys pulled out a .22-caliber rifle which Clark had taken from his father.

Clark said he was forced to drive to a secluded location where Van Orden was ordered out of the car. The boy with the rifle attempted to shoot her but when the gun jammed, a second boy joined him, and helped use the weapon to beat her to death.

All three were tried as adults on charges of conspiracy, stealing a vehicle and possessing a firearm during a crime of violence. The Fifth Court of Appeals later upheld their adult certifications, citing a previous hearing in which the district court considered the age, social background, the nature of the offense, prior delinquency record, current intellectual development, psychological maturity, past treatment efforts and the availability of programs designated to treat juvenile behavioral problems.

In an evaluation report, psychiatrist Dr. William Gold characterized Clark as “street smart” and determined all three boys were “beyond rehabilitative efforts.”

In a 2255 petition, Race said she strongly believes if the court had considered Clark had been neglected by his mother, who was a drug user and a prostitute, and that he had been shuffled between relatives and foster homes as well as other factors “he would never have received such a lengthy sentence.”

The petition was denied, leaving Race only one other option: asking the president of the United States to commute Clark’s sentence for time served. In the request, Race noted Clark has been a “remarkable inmate” who obtained his GED, has taken college courses, worked in a prison program for troubled youth and became an accomplished writer. Race has petitioned every president since 2016 to no avail.

“I firmly believe Mr. Clark deserves the chance to prove a young man can truly change,” she wrote. “I have never encountered a criminal client whom I believe in as strongly as I believe in Jermon Clark. He truly deserves a chance to be a productive adult outside prison.”

Clark said if he is released, he plans to devote his time and effort to prevent young people from following the path he did.

“God knows that I am truly sorry for my foolish actions and I can only pray that my fifty year sentence be shortened and I can become living proof that a person sentenced as a juvenile can change and both deserve and take advantage of a second chance,” he wrote.

Texas laws

Life without parole for capital murder offenders younger than 18 was eliminated in Texas in 2013, leaving a mandatory life sentence with the possibility of parole after 40 years as the only option.

Still, a life sentence for certain other crimes required serving at least 30 years before becoming eligible for parole — such as in McMillan’s case.

Reform proponents, however, say that term is still too long, contending the longer the offender is in prison, the less likely he or she can successfully integrate back into society.

Rep. Brad Buckley, R-Killeen, sought to change that in a bill calling for such cases to be reviewed after 20 years. The bill, known as the Second Look Bill, also would have required the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles to consider growth, maturity and personal background of youth offenders when deciding whether to commute a prison sentence.

Although the bill passed both the House and Senate, Gov. Greg Abbott vetoed the bill in June despite bipartisan support.

Abbott said he recognized the potential for change but believes the proposed law conflicts with instructions required by state law and therefore, would lead to “needless, disruptive litigation.”

Although disappointed by Abbot’s veto, Castillo said, proponents remain optimistic a revised Second Chance Bill will be introduced during the 2023 legislative session.

“No one’s asking … to just let them go free,” Castillo said. “We are looking for a meaningful review.”

McMillan’s first chance at parole comes up in the same year legislators and Abbott may consider a revised Second Chance Bill. Castillo said she is hopeful Abbott’s concerns can be resolved in a revised bill.

She also believes allowing a review after 20 years could help rehabilitate certain offenders because “it gives them hope .. something they can look forward to … and meaningfully engage in reform.”

Jerger said he doesn’t have enough details about McMillan’s situation to address the question on whether he deserves parole.

“Coming from a Christian perspective, I think everyone should be afforded an opportunity for grace, he said.

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.