My father isn’t the most emotionally expressive guy. He is quiet and stoic, not much in the way of words. Over the years during my prison stay, I received lots of cards from my parents, which meant my mom writing on their behalf. But there was one time during the year that I knew I could count on seeing my father’s distinct handwriting. Birthdays.

Personal items are kept to a minimum in prison. I had one metal box to store property, about the size of a small school locker. I kept very few things, mostly a handful of pictures. But always the birthday cards that contained the word “love” and my father’s signature. My father carefully conceals his vulnerability, so rare moments like these felt revealing and tender. The edges of those cards are worn from years of opening and reopening. Sometimes, I used to just stare at those overly sentimental Hallmark cards, with their depictions of cats doing silly things, and I would cry. I would run my hand over my father’s signature and would remember why I wanted to be free, why I wanted better for my life, and how all my struggles suddenly felt easier when I held that card.

Recently, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) announced the Inspect 2 Protect program. According to the agency’s website, the program is designed to allow for easier detection of drugs and other contraband. Inspect 2 Protect creates new regulations for offender mail and visitation. As I read the outline of the new regulations, I felt a surge of panic, even though I am now outside the gates.

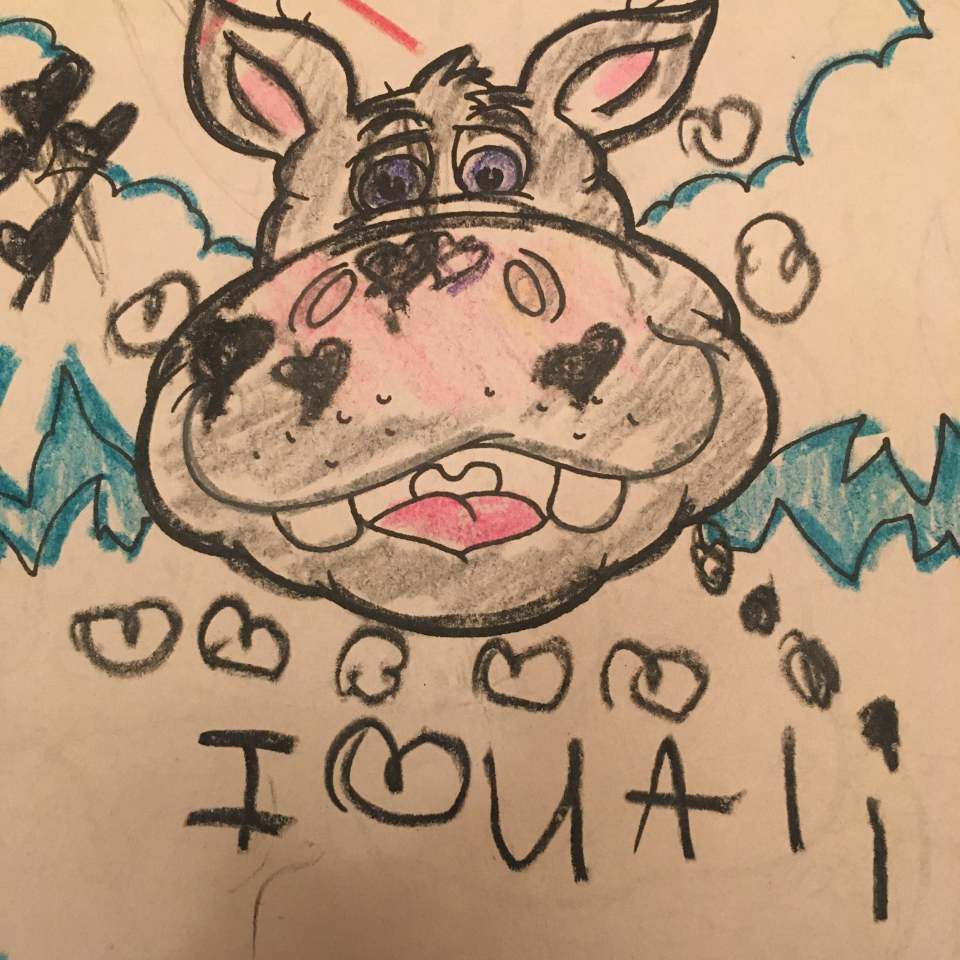

As of March 1st , TDCJ will no longer allow greeting cards of any kind. All general mail must be on standard white paper. No color. No stickers. No crayon pictures from children. No birthday cards.

I imagine that loss for a moment. The loss of connection so simple but instrumental in supporting and encouraging my emotional well-being during many hard years locked up. East Texas was so far away from Gatesville, where I was housed. My family could only visit once every three or four months, so my correspondence with them was crucial in maintaining our relationship. What could possibly be the justification for creating barriers like this for others still left in the system? TDCJ states that “In 2019, offenders received over 7.5 million pieces of mail. Approximately 3,500 letters per month have an uninspectable or suspicious substance.” This language is heavy but these words mean a variety of things, not just drugs. Such questionable substances could be anything from lipstick and perfume to glue and watercolors. I never knew anyone in the 19 years I spent incarcerated who was denied mail because of drugs. The suspicious substance in question was usually a badly-glued homemade card from a three-year-old to his mother. I look at that data and it seems unfair.

An array of Toon’s treasured cards, some decades old, that sustained her during incarceration.

Uninspectable mail totals to 42,000 a year. That leaves the remaining 7.458 million other pieces of mail completely harmless, but now subject to denial. The mail regulations are not the only thing about the program that concerned me. Inspect 2 Protect includes changes to visitation. Canines will be used to search visitors for drugs. This sounds reasonable at first glance, but the problem is that drug-sniffing dogs are not always accurate. According to the new regulations, once a dog makes an alert, whether valid or not, the visitor will be told to leave immediately.

I imagine this loss, too. My parents would drive four hours one way from Kilgore to Gatesville to visit, often planning around work and other obligations. What if it were me anticipating their arrival, sitting in the dayroom waiting to be called to visitation, but no one calls. What if my family were told to leave after traveling such a long distance and not being able to protest or appeal to anyone to reconsider? What if they would have eventually given up trying?

Drawings like these, made by the children of exoneree Hannah Overton, will no longer be allowed to be sent to those incarcerated in the TDCJ, under Inspect 2 Protect. Pictures courtesy of Maggie Luna.

According to a letter of opposition to Inspect 2 Protect signed by dozens of organizations like the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, “Studies over the past 40 years from institutions like the American Correctional Association have consistently found that incarcerated individuals who maintain close contact with their family members while incarcerated have better post-release outcomes and lower recidivism rates.” Whenever I felt disconnected from my family and the outside world, the more disconnected I felt from myself. In the absence of connection, apathy threatens to take root and grow in the spaces where empathy should.

Any barrier between the incarcerated and their loved ones is a barrier to rehabilitation and public safety. I know that drugs and contraband are a problem. I, of all people, understand the realities of these. Nonetheless, the right solutions look proactive, not reactive. We should shift the focus to the core issue, which is substance abuse and addiction. Programs using trained and certified incarcerated peer support specialists within the prison system would be a proactive step in the right direction.

I celebrated my birthday a couple of weeks ago. I went to dinner with my parents. The food was good. The gifts were nice. But the card was what I still looked forward to the most.

Jennifer Toon is a formerly incarcerated criminal justice advocate who was born and raised in East Texas. She attended Kilgore High School, and U.T. Tyler, and studied journalism at The University of Houston. She has 25 years of criminal justice involvement inside and outside the gates. Jennifer has written for the state prison newspaper, The Echo, for over ten years and as a freelance writer she has published work with The Texas Observer and The Marshall Project.

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.