Photo by Jamie Maldonado.

My name is Foy Magee. My subject is picking cotton. I was born on December 26, 1927, in the New Hope Community, Henderson County, south of Brownsboro about three miles. I am 91 years old. I am the seventh of eight children, five boys and three girls. When I was 18 years old, I joined the Marine Corps. They wanted me to stay in service when the war was over. I wanted to go home and see my mama and go to college. So I came home and traveled some, but East Texas has always been my home. I just love East Texas.

Living on a farm, I planted cotton with a mule in front of the planter when I was 9 years old. I picked cotton from when I was 8. The old timers told us to watch the hickory trees. When the leaves on the hickory tree were as big as a squirrel’s ear, it was time to plant cotton. That’s what the old timers went by.

When I was a junior in high school, I wanted to find a job during the Christmas holidays. All the crops were picked in East Texas. My uncle George was working, picking cotton in Roby, in West Texas. I never liked picking cotton, but it was a way us country boys had to make money. So my cousin, Chester, and I hitchhiked to Roby to pick cotton.

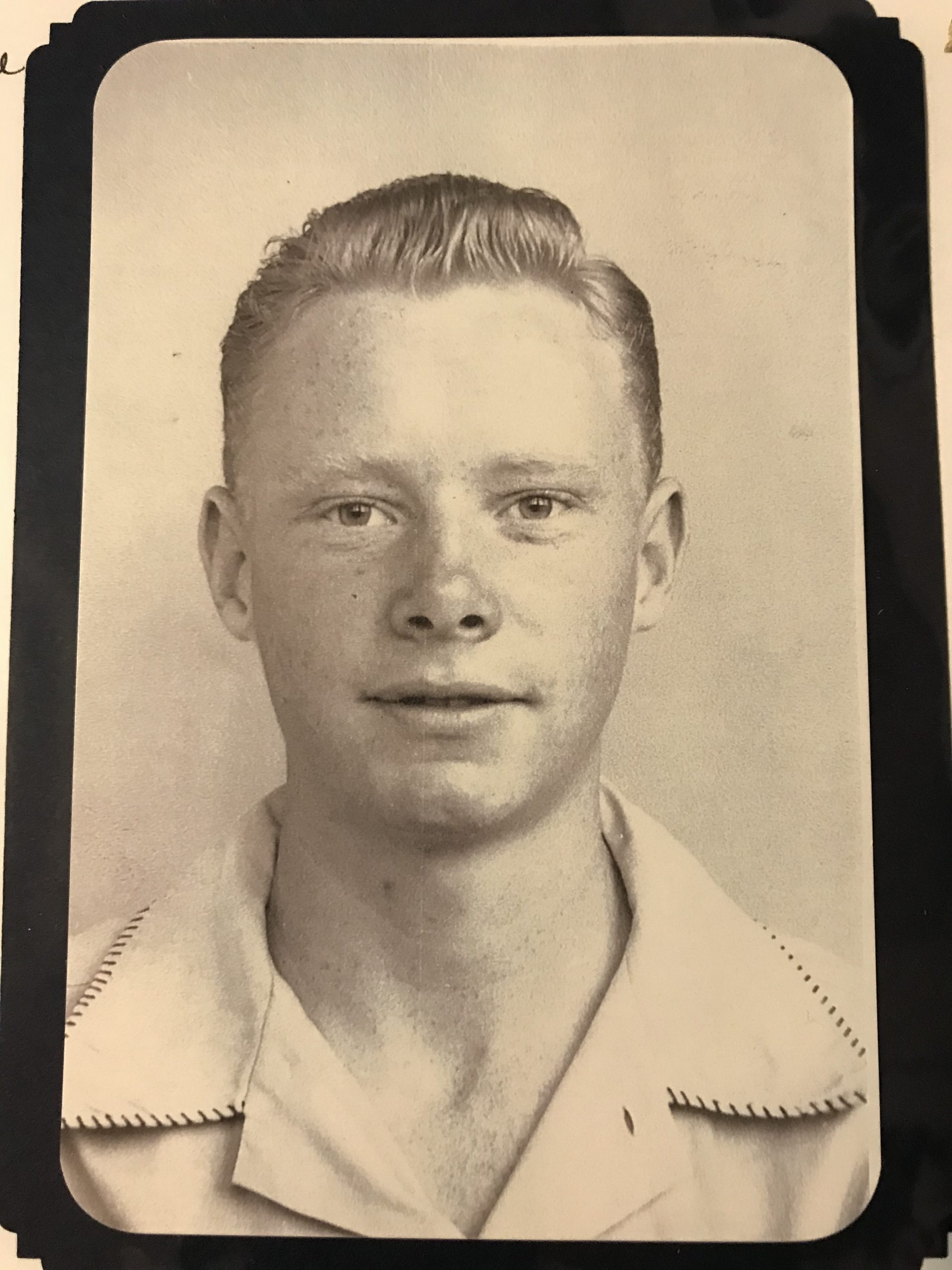

A portrait of Foy from his high school years.

A portrait of Foy from his high school years.

There are two ways to pick cotton. Cotton is ready to pick when the burrs get hard and open to release the cotton. In East Texas we picked cotton earlier than other places, when the leaves were still green. If we waited until we could snap them off, the cotton bolls would fall to the ground. So we picked the clean cotton bolls. The sharp ends of the burrs would stab our fingers. It hurt and was slower, but we didn’t have to fill our bags as often.

The other way is to snap cotton. When the cotton plant is dead, after the first frost, we could snap off the whole top—bolls, burrs, and all. It went faster, and didn’t hurt as much. But it was a lot trashier and you had to fill up more sacks to make a clean bale of cotton.

Four of us picked cotton for Mr. Menshew — Uncle George, Chester, Tony and me. Mr. Menshew was an old bachelor, and his sister was an old maid. She cooked for us, and we stayed in their house with them. Mr. Menshew never could remember my name, so he called me “Red.”

Every morning we would get up at five o’clock and go outside on the porch to wash our hands and face. Sometimes we had to break the ice on the water. Boy, was that cold! It sure woke us up. We had eggs, bacon, milk, and plenty of biscuits and jelly for breakfast. We sure did eat that jelly. That was the best jelly I ever ate.

We rode the tractor to the field and picked cotton. We were snapping the cotton, breaking off the tops — bolls, burrs and all. We quit at 12 o’clock for lunch at the house, then worked until sundown. At night Mr. Menshew played dominoes with us. After a few plays, he could tell what each of us had in our hands.

It rained for a couple of days and Mr. Menshew’s sister sure got upset because we sat around the house eating and not picking cotton.

One day, Mr. Menshew wanted a bale of picked cotton, where we just pulled out the clean cotton bolls and left the burrs and stems. People used 12-yard sacks, 10-yard sacks, and little kids had six-yard sacks. I used a 10-yard sack. It weighed about 80 pounds, filled. When I picked cotton, I had to bend over all the time, picking with both hands and dragging a heavy sack. I had to shake the sack to move the cotton to the bottom. The more I picked, the heavier the sack was to shake down. When my back got too tired, I had to get on my knees and crawl. I was picking that cotton with dead burrs. Them ol’ sharp ends stuck on the sides of my fingernails and under the cuticles. By the end of the day, my fingers were bleeding, you know. So it really was a mess trying to get picking and really made them sore.

When my sack was full, I went to the scales. I tried to pick rows so that I ended up with my sack full and the end of the row close to the scales. Then I weighed the sack, subtracted the weight of the sack, and dumped the 80 pounds of cotton in the trailer.

That day I picked over 400 pounds of cotton, first time in my life. My older brother, J.P., he picked that much nearly every day. His hands were a lot bigger than mine. He could hold a lot more cotton in his hands before he had to reach back and put it in the sack. But this was my first time. I was really proud of that 400 pounds!

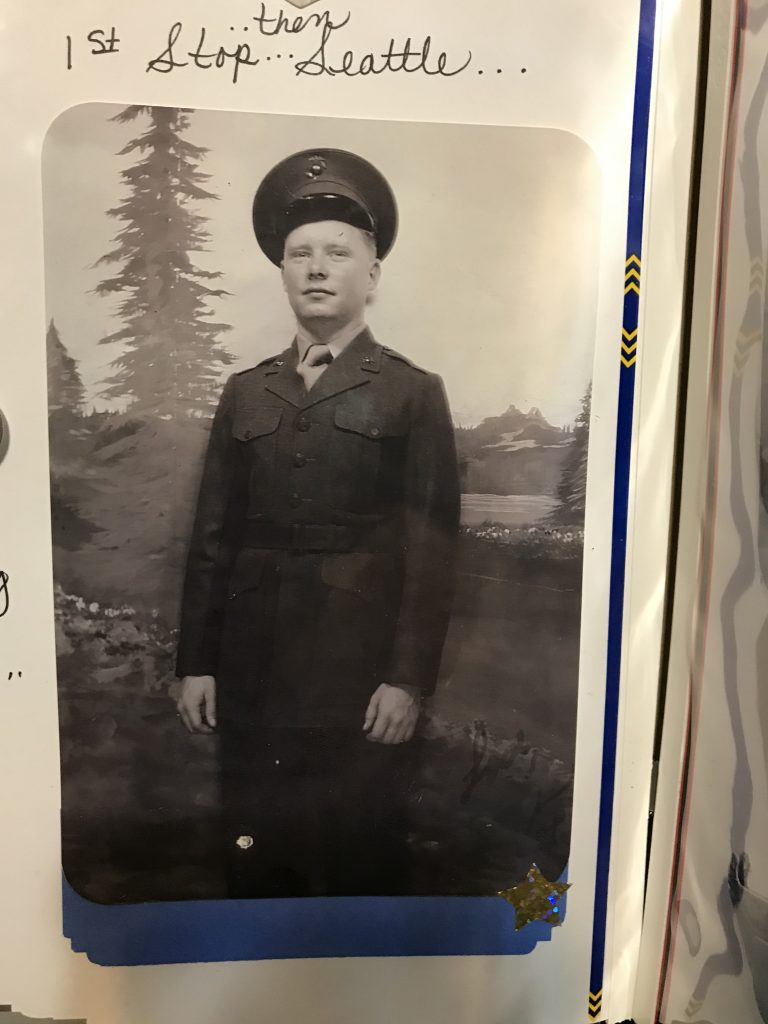

A photo of Foy soon after he joined the Marines.

A photo of Foy soon after he joined the Marines.

All the men went to Roby on Saturday afternoon. Mr. Menshew played poker. He was a gambler. He didn’t drink. He said he’d let the men drink for half the night…and then he’d start winning. The way he talked, he won all the time. When we got ready to go back to the house, we found a note on the pickup. “Red, drive the pickup home.” I missed the turn, and when I saw the bright lights of Sweetwater, I turned around and we went back to the house.

After two weeks, Christmas vacation was over. We had money in our pockets, so Chester and I rode the bus back home and started back to school.

It was a good vacation. I gave my money to my mama to keep for me for when I needed it.

I had picked my first 400 pounds of cotton.

Have a true personal story about life in Tyler and East Texas you’d like to share at the next Out of the Loop storytelling event? Email storytelling director Jane Neal and describe your story in a sentence or two.

“Living in East Texas, I’ve traded in Tyler all my life,” says Foy, whose family has worked the land in East Texas as farmers for three generations. “East Texas is where I got my schooling and my Christian values. I’ve raised my family, farmed and ranched in East Texas. In the Marines, I was in California and Washington State. Working in the oil fields, I traveled in Louisiana and Mississippi. I’ve visited Michigan and South Carolina. East Texas has always been my home.” You can read even more of Foy’s story, in his own words, here.

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.