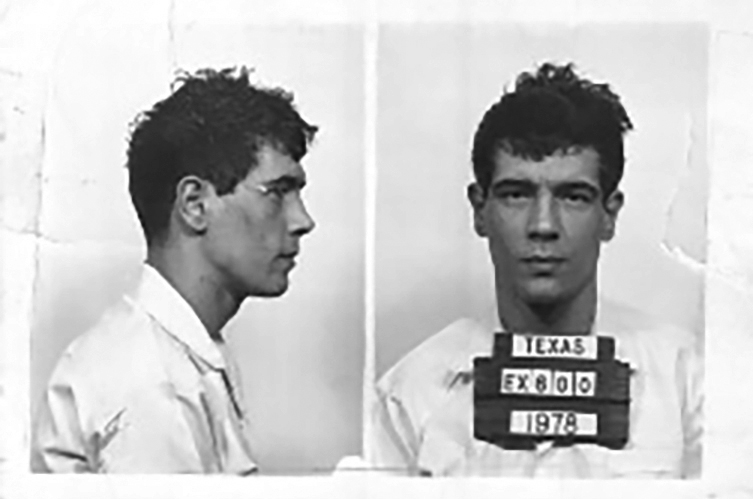

If it seems like a lifetime since former death row Kerry Max Cook first made headlines, it’s because it has.

After 45 years, he remains centered in one of Smith County’s and the state’s most controversial murder cases involving an unprecedented three trials, legal exoneration, new evidence and the rejection of his actual innocence claim.

It’s been six years since a judge reviewed his case and determined a reasonable juror still could convict Cook of murder in the 1977 mutilation death of Linda Jo Edwards in Tyler.

Whether he will face another trial, however, still is in question as the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals reviews that judge’s decision — an appeal process that is now entering its seventh year of review.

“It’s an interesting story and a very long case, but we’ve been waiting for how it ends for quite a while,” District Attorney Jacob Putman said.

The decision has been on appeal longer than Putman has been in office.

“Inheriting cases is part of getting elected to any office, but most of the time you don’t deal with a case that is this old,” he said. “This one has a longer history than most.”

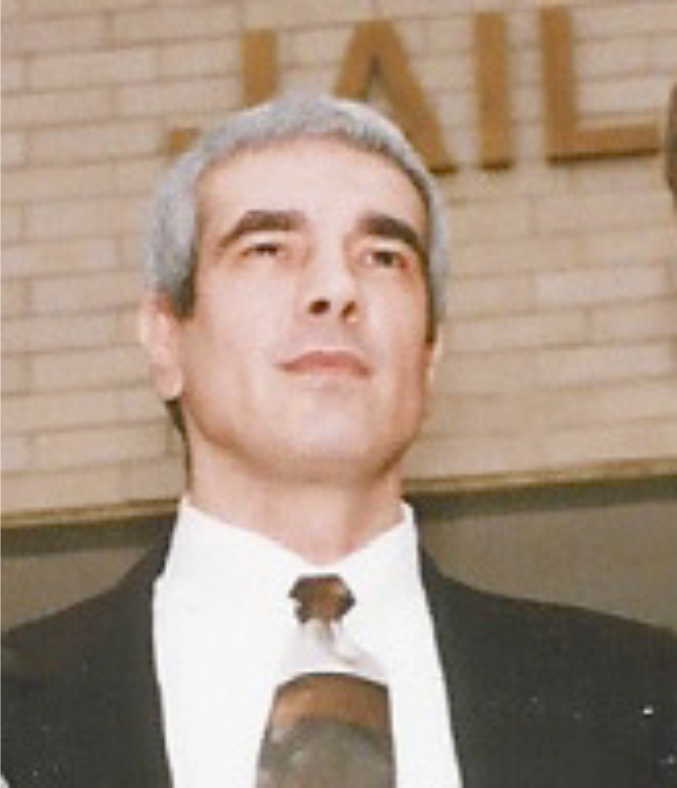

Not only did Putman inherit the Cook case, but so did his two predecessors, Matt Bingham and Jack Skeen, Jr.

Skeen, who served an unprecedented five terms as district attorney, is set to retire at the end of the year after serving five terms as a district judge. As a prosecutor, Skeen oversaw two trials, numerous appeals and hearings and a plea negotiation involving Cook.

To recount all the details of this case would take volumes, but a brief review is necessary to understand just how this case came to be one of the most complicated and controversial in Smith County history.

Background

Edwards, a 22-year-old Bullard native, was found dead the morning of June 10, 1977, in a south Tyler apartment she shared with a co-worker. She had been beaten, stabbed and parts of her body mutilated.

Cook was arrested after police identified his fingerprints found on the apartment’s sliding glass door leading to the patio. Cook initially claimed he did not know Edwards and had never been inside her apartment. He said he left his fingerprints while window peeping.

Fifteen years later, Cook claimed he met Edwards at the apartment complex swimming pool, and she had invited him back to her home to make out. He insists he did not kill her.

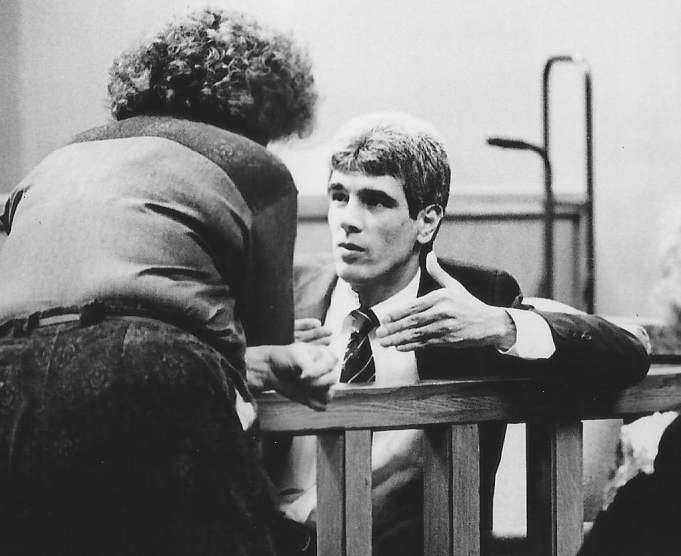

In 1991, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals overturned Cook’s first trial and death sentence based on a ruling that he was denied his right to counsel during an interview with a psychiatrist. His retrial in 1992 ended in a mistrial after jurors deadlocked 6-6. The jurors uncovered a missing nylon stocking among the evidence during deliberations. The prosecution had contended Cook stole the stocking to carry body parts from the murder scene.

Two years later, a second retrial ended with a conviction and another death sentence, but that verdict was overturned in 1996 due to prior prosecutorial misconduct. Just before his third retrial began in 1999, opposing attorneys reached an agreement in which Cook was convicted of murder and sentenced to time served — 20 years.

That conviction, however, was set aside in 2016 after DNA tests revealed a sample from the victim’s underwear matched her former lover and that he, James Mayfield, admitted lying about the last time he was with the victim.

In hearings six years ago, a defense attorney argued that new evidence was enough to prove Cook’s actual innocence — a finding required before Cook can pursue a lawsuit against the state for wrongful conviction.

In his July 2016 opinion, Judge Jack Carter ruled the new evidence addressed only the question of who had sex with the victim, not necessarily who killed her.

“It is definitely helpful to Cook’s defense,” Carter wrote, “but this court does not find that it unquestionably proves that Cook is actually innocent.

It is this court’s conclusion that a reasonable jury would not necessarily acquit Cook after hearing both new exculpatory evidence and the previous evidence of guilt.”

The DNA evidence legally exonerated Cook but did not necessarily support a finding of innocence.

Legal exoneration, Putman explained, is quite different than being found not guilty.

“It means the charges are restored to the point prior to trial. That there is a presumption of innocence,” he said.

Legally, Cook could be retried again on capital murder charges, but Putman said it is too soon to say how his office will handle the case.

“It depends upon what the court decides,” he said.

Editor’s note: Kerry Max Cook declined a request to be interviewed for this article, referring all questions to his attorney. His attorney did not respond to numerous telephone messages seeking a response.

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.