When Amy Anderson schedules an interview for a child care teacher, she’s never sure if the candidate will show up. Even for new hires who have completed the required paperwork, a background check, fingerprinting and begin training, it’s not an unusual outcome – no two-week notice, and sometimes just a text message resignation.

“It’s difficult. It is frustrating, but there’s nothing you can do about it,” said Anderson, the director of the First Christian Church Early Childhood Center in Tyler.

Staffing challenges contribute to the current “crisis” in a child care industry already struggling to keep up with demand, experts said. In Tyler, licensed facilities as a whole offer slots for 5,800 children, but the demand for seats — especially for infants and toddlers — far exceeds the supply.

Waiting lists are as common as help wanted advertisements.

Directors like Anderson want to find and keep reliable teachers entrusted to care for the children of others as if they were their own. They need teachers who love children, understand parental concerns and are dedicated to engaging, educational activities but who also are willing to work for the national median wage of $11 an hour or less.

“It is a very, very tall order for what we’re looking for, for the prices we can pay,” Anderson said.

The child care workforce already is among the lowest-paying professions for degree holders, according to the Center for American Progress, a non-partisan public policy organization located in Washington D.C.

“Despite the high cost of care, child care programs are typically just scraping by — and only able to do so because early educators are paid so little,” according to a center’s 2020 report.

Providers experienced “crisis mode” even before the COVID pandemic, and although most are making a comeback, they face fierce competition for a returning workforce eager to make more money.

Entry-level child care positions require applicants to be at least 18, have a high school diploma or equivalent and pass a background check. The wage issue leaves potential care workers weighing options in favor of what is best for their individual circumstances.

“We bring in a lot of teachers that love kids, but when they’re looking at being able to go make $12 an hour serving fast-food, with benefits, versus having 15 2-year-olds depending on them … for eight hours a day … when push comes to shove, it’s just a hard decision to make when you have a family to feed,” said Andria Horton, executive director for Champions for Children in Tyler.

The non-profit organization provides training and support for caregivers, teachers and families as a United Way of Tyler and Smith County partner.

Based on information obtained from directors and teachers, Horton said starting pay for teachers in Tyler and Smith County increased from $8.50 an hour in 2021 to $9.50 and hour in 2022. Experienced teachers earn slightly more, but still 94% make less than $15 an hour, she said.

Jaquinta Lee, executive director at Tyler Day Nursery for the past 15 years, said she has worked to adjust wages to be more competitive, but they still face a staff shortage. She said she would like to have at least seven more teachers.

“Starting pay is $11, but if they have a CDA (Childhood Development Associate) or higher, we pay more for a degree,” Lee said.

Tyler Day Nursery opened in 1936 as a Tyler Council of Church Women project providing child care for children of low-income and poverty level families. Although a small portion of its operating budget comes from tuition fees, it relies upon funding from the Council of Church Women, the United Way agency, local churches and synagogues, foundations, various civic and social groups as well as individual donors.

Lee said she also has experienced applicants who fail to respond to her inquiries and continues to search for a way to attract qualified people.

“That’s the biggest challenge I’ve had for a really long time,” she said. “It’s really gotten bad during COVID.”

Horton said she is working with directors to hopefully find an answer.

“No one is going to blame them for going and seeking out a higher wage,” Horton said. “But we are looking at what we can do to make the work environment a little more beneficial.”

Why quantity and quality counts

Staffing is a critical issue for child care since laws require licensed centers to maintain specific teacher/child ratios and space requirements.

For example, in Texas, a center with 13 or more children must provide one staff member for every four infants (up to 11 months). It also costs a center more to provide for infants and toddlers. The older the children, the less it costs and the number a teacher can supervise increases.

When a teacher calls in sick or there is an unfilled teaching position, directors must find legal ways to compensate such as giving more hours to other teachers, shifting teacher assignments, relying on part-time workers or filling in themselves.

In rare instances, directors may close a specific classroom until teaching positions can be filled. Some centers must reduce their hours of operation due to staffing issues. In one instance, a child care center that normally closed at 5:30 p.m. began closing at 2 p.m., Anderson said.

“That doesn’t help parents who work all day, and so I had some of those parents calling me to see if we had room for their kids,” she said. “I did not. We’re full.”

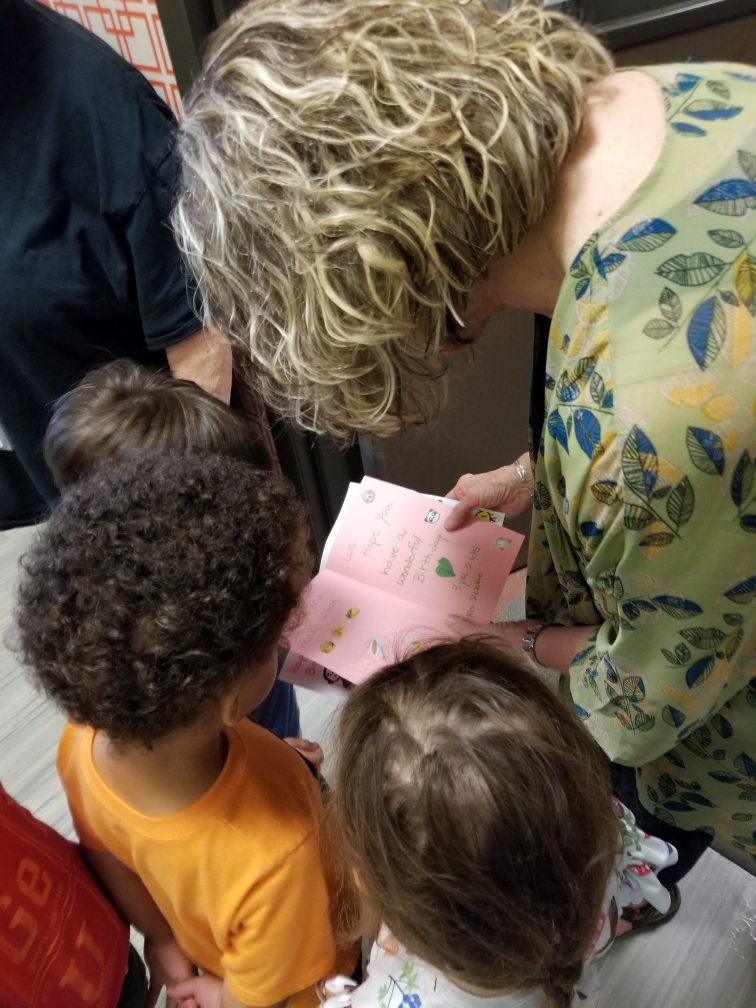

But providing quality care is more than just numbers for providers. Horton said her directors are 100% committed to quality of care.

“What we hear is a director saying, ‘because I can’t commit to having a teacher in that classroom every single day, we’re having to close classrooms while at the same time I have a waiting list of people,’” she said.

Finding the right person to fill those vacancies is quite a task.

“I always expect excellent quality. You have to,” Anderson said. “I can’t just settle for a warm body in a classroom. That does not work for kids, parents, me, anybody. That just can’t happen.”

Anderson said what she looks for in a candidate is the “it factor.”

“Some teachers just naturally attract kids, and that’s the kind of teacher that we really want,” she said. “You’re either a child magnet or you’re not. We definitely want child magnets if at all possible. Sometimes that is very hard to determine.”

Gail Brown, executive director of the early education center at Grace Community School, agrees that finding the right employees is a challenge.

“It’s hard to always keep them, too. Once they get in there, they realize that the work that they do is pretty intense and hard,” she said. “So those are the ones who weed themselves out.”

Pandemic impact and other factors

The spread of — or fear of spreading — COVID upended businesses at every level of every industry across the nation. A portion of the workforce stayed at home to do their jobs and took their children with them.

“We all thought we could just stay home, and the kids can stay in the playroom, and we’ll just work, and it will be great,” Horton said. “When the parents became teachers and took on that role, they realized just how valuable child care truly is.”

With fewer children placed in their care, centers didn’t need as many teachers. The pandemic forced some child care facilities to close either temporarily or in some cases permanently. Others, however, struggled through but took on extra tasks and new protocols to maintain a healthy, clean environment.

As the pandemic appeared to be on the decline, parents began returning to work and taking their children to care centers.

“Now that is has picked back up, we’re having to restaff and hire … trying to get back on track with that,” Brown said. “It’s hard, but really it’s no different than when you go to any restaurant right now … to hire people that are willing to put in the time and effort to work.”

But the workforce has changed in a variety of ways. In Tyler and Smith County, females age 18-81 make up 98% of child care workers, Horton said.

“There was a significant pool of the older population who were absolutely loving, nurturing, great caregivers, but when those caregivers became at risk being around that many children from that many households, they really were hesitant to come back when their centers opened back up,” she said. “That has created a situation where we have to replace those really highly experienced, highly qualified staff and find new teachers to come in and develop that experience.”

Child care facilities also utilize college students, most of whom work part time around their class schedule.

“A lot of students work for us and that’s wonderful, but sometimes their schedules change,” Anderson said.

Providers said they are accustomed to losing student workers due to conflicting schedules, school transfers and graduation.

Unique industry

In some ways, child care facilities face the same staffing challenges as fast-food restaurants and retail businesses, especially in the wake of the COVID pandemic. Competition for workers prompted higher hourly wages, signing bonuses and even flexible hours — incentives not always possible in the child care industry.

Increasing wages for child care teachers also is problematic since the service is usually tied directly with the fee parents pay. Whereas fast-food owners can adjust work schedules, increase prices or hire fewer workers to fund higher wages, child care operators generally don’t have those options.

Higher wages for teachers — raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour, for example — often means higher fees for parents who often are just scraping by. Infant child care costs families an average of $11,000 a year, and only one in six families are eligible for child care subsidies, according to the Center for American Progress.

The high cost and limited availability of child care also disproportionately affects people of color, according to an American Progress Report.

That report also shows Black Americans are nearly twice as likely as non-Hispanic white families to make job sacrifices because of child care challenges. Hispanic families with infants and toddlers are less than half as likely as non-Hispanic white families to use licensed child care, according to the report.

“It’s a true Catch 22 of the child care crisis. Who out there is getting rich off this system? There’s nobody getting rich off the system,” Horton said. “This is essential work.”

Investing

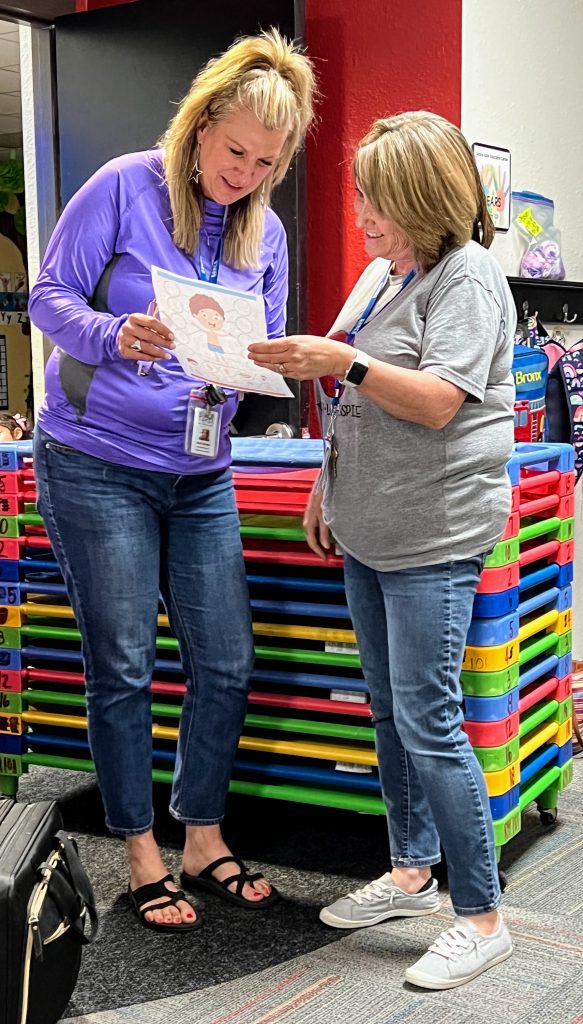

She said Champions for Children suggests a variety of strategies to keep a center within budget and to build a staff of long-term employees.

“We encourage our centers to make the center an excellent place to work … to give them flexibility, especially for those who may want to pursue higher education,” Horton said.

Although centers share some common challenges, each has their own unique circumstances to consider.

Chris Pullium, the senior minister at First Christian Church, said monthly fees paid by parents fund wages for teachers. Overhead costs — space and utilities for example — are absorbed by the church as a non-profit entity.

“It’s not a money-making operation for us … it’s a ministry for our church,” he said. “I just think there is an incredible need for quality child care, especially for infants.”

Despite building infant bed availability into their program, the center currently has a waiting list for that age group.

“As soon as couples find out … we’re filled up nine months in advance,” he said.

Pullium and Anderson said they make their best efforts to provide well for the center’s staff but still face hiring and retention challenges.

Anderson said she only has one employee who has been with the center since it opened in 2021.

“I’ve had good teachers, solid teachers, that are just part of the family here … come to me and they just can’t make it on what we pay now,” she said.

“Through the generosity of our church and our ECC committee, we’ve been able to give them (employees) some added incentive to stay.”

At Grace Community, Brown said she is fortunate to be able to offer a benefit package — including vacation, sick days, medical insurance, retirement plan — to full-time employees.

“So, that’s a huge deal to attract people who come to work with us, stay with us,” she said. “Those are kind of coveted spots, because not everyone is full time.”

She said they also have increased their salaries — most above $10 per hour — for the upcoming year to help stay competitive.

She said investing more time into training also helps their retention rates for Grace Community’s non-profit program which operates child care centers in Tyler and Lindale with a combined enrollment of more than 300 children. Although there currently is a waiting list for the infant group at the Tyler location, there are slots available in Lindale.

“We need qualified people who understand the commitment to these children and these families once they start working there,” Brown said. “You’ve got to invest more to get more.”

Still, openings are sometimes hard to come by, since the program operates by promoting age groups together to a higher level when the time comes, she said. She said most of the children in their care stay with the center until they enter kindergarten at Grace Community School.

“So, if each class is full and remains with Grace Community, the classes tend to remain full as they graduate to the next level. That makes availability at the infant level even more important.”

Brown said the church also invests in children by teaching the Bible.

“Everything we do, we are teaching Jesus first … investing in our children and families,” she said.

Battle plans

Horton said Champions for Children also offers a variety of training programs, educational materials, budgeting plans, help in obtaining the maximum reimbursement in subsidized funding and receiving relief packages from the federal Build Back American Plan.

She said partnerships with Tyler organizations often provide resources to promote programs such as music and movement; and social emotional lessons in the classroom.

Offering students a chance to earn a Child Development Associate Certificate, for example, helps them to negotiate for higher wages, she said.

“We’re all working together to make sure students have a clear pathway that if they are willing to put in the work and they can see it through to the end … they can have sustainable, long-term careers in the area of early childhood,” she added.

Horton said she also would like to see more employers create their own child care centers as an “extra perk” for their employees.

“There’s a lot of good reasons not to do it, but for the right company with the right motivation, I think it has the potential to be a great culture building incentive,” Horton said. “It’s an incentive for people to come to work for you and for people to stay.”

Lee said she also looks for potential employees who have that special quality.

“I want someone who has a passion to deal with children,” she said.

“Everything that is standard (day to day operations), I can teach that, but I can’t give them that passion.”

And like the other directors, Lee emphasizes the importance of investing in the wellbeing of children and reaping rewards other than financial gain.

“I worked five or six years in the classroom before coming into the office,” I fully understand that I’m not going to get rich in dollars, but I get rich when I see my kids 10-12 years later.”

She said seeing one of her students receiving a high school honor was rewarding for her, too.

“When I saw that, it tickled me to pieces to see a child that I have changed their diapers … watched her on the playground … is now the local high school student of the month,” she said. “You can’t give me enough money for that.”

Vanessa E. Curry is a journalist with nearly 35 years of experience as a writer, editor and instructor. She earned a B.S. degree in Mass Communication from Illinois State University and a MSIS degree from The University of Texas at Tyler with emphasis on journalism, political science and criminal justice. She has worked newspaper in Marlin, Henderson, Tyler and Jacksonville, Texas as well as in Columbia Tennessee. Vanessa also was a journalism instructor at the UT-Tyler and Tennessee Tech University. Her writing has been recognized by the State Bar of Texas, Texas Associated Press Managing Editors, Dallas Press Club, and Tennessee Press Association. She currently is working on publishing two books: “Lies and Consequences: The Trials of Kerry Max Cook,” and “A Gold Medal Man, A biography of Kenneth L. “Tug” Wilson.

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.