According to a report published this fall, Texas is the second-most diverse state in America when it comes to socio-economic, cultural, economic, household, religious, and political diversity. One in six residents in Texas is an immigrant, and 15 percent of Texas citizens have at least one immigrant parent. Here in Smith County, eight percent of our population is foreign-born.

In a political climate where the topic of immigration raises heated emotions, it can be valuable to hear the stories of real people behind the statistics. Here, we introduce you to three Tylerites who came to our community from other countries, and have helped shape Tyler’s increasingly diverse cultural landscape.

Ximena Kelley

Ximena Kelley, 46, was born in Santiago, Chile, but her life has been shaped by experiences in many countries. She’s immigrated four times, from Chile to Venezuela, then El Salvador, and finally the United States.

Her family move constantly due to conflicts in Central and South America. The first time, Ximena was barely one year old. She says her father, a distinguished professor at a Chilean college, was being pressured by an increasingly totalitarian government to “brainwash” his students.

They moved to his home country of El Salvador and lived in “nice” neighborhoods, near embassies and the home of the president. This made her street a target for guerrilla insurgents as civil war broke out in 1979. “There were bullet holes in my house,” Ximena says. “One hit my pillow and my side table.”

The family left in 1979 to live in Venezuela. Ximena said she and her siblings were finally able to have a “normal” childhood, but were scared that war would follow them yet again. “We were at a friend’s house, and the mom dropped one of the lids from the pot on the ground,” Ximena recalls. “My brother, my sister, and I screamed and got under the table.”

It’s a lesson she’s passed onto her own children here in the U.S. “I always tell the kids, don’t take for granted living here because you don’t have to go through what we went through,” Ximena says.

In 1984, after the El Salvadoran civil war ended, the family left Venezuela and moved back to the capital, San Salvador. There, Ximena met her ex-husband, got married, and had two children. In 1997, her former husband landed his first medical residency in New York City. Before Ximena moved to the States, she had been in dental school. When she came to America at 23 as a non-English speaker with two children under three years old, she felt no choice but to become a stay-at-home mom.

“Nobody knows what I went through in my life,” Ximena says. “It was just me against the world.”

She made a deal with her neighbor. Every day, she would pick up her neighbor’s children from school and watch them. One night a week, the neighbor would watch Ximena’s children so Ximena could attend evening English classes at the public library two bus rides away.

“I was raised to be a strong woman,” she says. “If you fall down and they wanna break you, you get up, go on, and show them.” Today, Ximena works as a respiratory therapist at a local hospital, and speaks perfect English.

Ximena had her third child, Luis, after immigrating to America. For her other two children to receive their green cards, and to secure dual citizenship for Luis in El Salvador, it has cost Ximena and her ex-husband nearly $20,000. Ben and Maria will be receiving their full citizenship in about a year. Ximena is two years away from getting naturalized.

“It’s hard,” Ximena said about earning citizenship. She’s lived in the United States for 22 years, but is determined to earn her full legal citizenship status no matter how long it takes. “Yes, it will cost you,” she said, “but in the long run, it’ll be better for you and your family.”

Ximena got remarried in 2008 to a man named Alex Kelley. Her last name was Arce in her previous marriage, and Ximena says she was treated differently with that name. She tells the story of being pulled over by a police officer in Gilmer a few years ago. After handing over her driver’s license, she was asked for her “papers,” despite being dressed in her hospital uniform and being stopped only for a broken taillight.

When she married Alex, she says, people’s attitudes toward her changed: “They think I’m a white girl.” She and Alex both went to her interview for her green card. They had been married for many years at that point, but the interviewer thought Alex was her immigration lawyer.

Overall, it was a great day. “At the end of the interview, [the immigration officer] said to me, ‘People like you [are] the ones we want to welcome to this country,’” Ximena recalls.

Edwin “Ed” Santos

Ed Santos, 53, hates when East Texans say “same old, same old” when asked how they’re doing. The way he sees it, Americans have all the options in the world, and yet many people here seem to be unhappy.

He calls the Philippines, his home country, a place of smiling and joyful people. “To us, every day is a gift, and we truly live to appreciate it,” Santos says. “The only promise is what you’ve got now.”

Santos immigrated to Tyler in 1991 from Manila, the capital of the Philippines. He was recruited straight out of college by the East Texas Medical Center to work as a physical therapist. He had also been recruited by a hospital in Boston. He told E.T.M.C. and the Boston hospital that he’d work for whoever could process his visa sponsorship fastest.

Santos was coming to America on an H-1B visa. It’s a work visa for people with highly coveted or special skills needed in America, but it requires that the company they work for “sponsor” them, a complex and often very expensive process. E.T.M.C. got the paperwork done first, and Santos has lived and worked in Texas ever since.

Santos jokingly says the number one export of the Philippines is Filipino people, and that many immigrate to Europe, the Middle East, and the U.S. for work. While Santos remembers his home country as beautiful and close-knit, he notes that the legacy of Spanish colonization has left many Filipinos struggling with corruption, income inequality, and poor health. “Not just living, but surviving,” Santos says.

When Santos was growing up, his parents were a part of an emerging middle class in Manila. His father worked in the sugar industry, and his mother worked for Shell Oil Company. “She spoke better English than I did,” Santos says.

The Philippines has over 7,000 islands, 200 of which are habitable. But nearly every island speaks a different language, making it a land of many tongues. In that way, coming to America felt somewhat familiar. “When you come to Tyler and East Texas, they don’t speak English,” Santos says. “They speak Texan, which is totally different, y’all!”

Santos joked about having to learn local colloquialisms, like how a person might say something mean, but as long as they add a “blessing,” it’s all good. “Your daughter is so ugly—bless her heart!” Santos offers, laughing, as an example.

Overall, coming to East Texas was a major culture shock. Tyler had a population of just 55,000 at the time. Manila was a city of 16 million. “It was lonely,” Santos says. “It still is.”

The only person he knew in Texas was his father’s sister, who lived in Houston but “didn’t even know where Tyler was.” And he had a hard time finding community. For instance, it’s typical for Filipinos to bring extra food at lunchtime and invite people to eat with them. “Nobody in the Philippines eats by themselves,” Santos says. In America, he jokes, you only get invited to eat with someone once, and then you don’t get invited again.

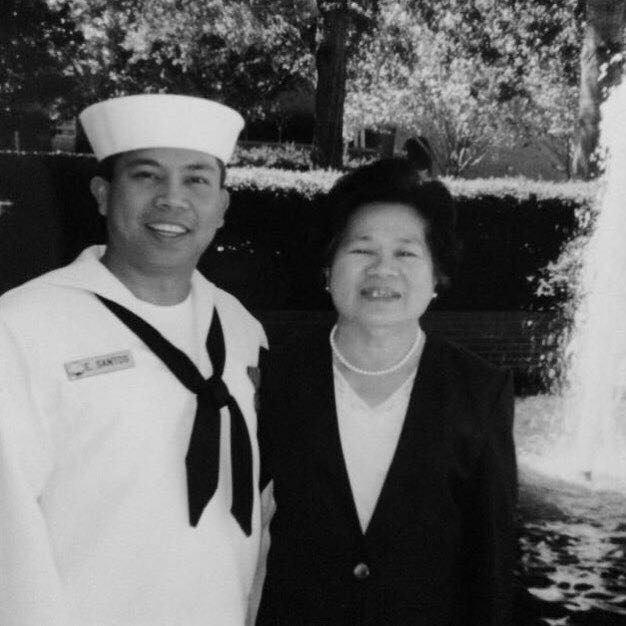

Santos joined the Navy reserves in 1996 hoping to speed up his citizenship process — and also because he was “working in Lubbock and there was nothing to do.” He stayed in the Navy Reserves for eight years. Being in the military can cut the wait time for a green card down from five years to three, but Santos still had to wait the full five years due to a budget crunch and slow processing time.

Santos finally became an American citizen in 2001. Today, he is active with several local organizations and causes including Tyler’s Better Business Bureau, Sunrise Rotary Club, the Cathedral of Immaculate Conception, veteran’s affairs, and the Filipino American Association (FAA).

Ed says his volunteer activities give him “purpose,” but also helped battle the loneliness of coming to America on his own. He joined the FAA “to be able to help and pay forward how those who were here before me were able to help.”

Santos says that today, there’s a new wave of immigrants coming from the Philippines to East Texas. “We have good [medical] facilities here, we have a competitive pay scale, plus it’s manageable traffic,” Santos says. “A big draw is the school system, because most have kids.”

Santos says these newer arrivers are far more prepared to feel comfortable in East Texas than he was. Most have fluent English-language skills, and already know how to drive.

Despite all the cultural differences and taking a long time to feel at home here, Santos loves Tyler. “We are a lot more alike than we are different, in terms of what really matters,” he says. “What we actually aspire for, dream for, what we actually want. We want safety, security. We want to be with our loved ones, and we want them to be prosperous. It’s the culture. It’s not wrong or right, it’s just different.”

“I am very proud to be an ABC,” Santos said. “An American By Choice. ”

Aji Sahko

Aji Sahko, 22, graduated in May from the mass communication department at the University of Texas at Tyler. She came to the United States on a student visa when she was 17, following her brother to study at U.T.T. Her home country is The Gambia, a very small west African country almost entirely surrounded by Senegal, though she was born in England. Gambia’s population is just two million, less than the number of people living in Houston.

She’s now back in The Gambia, working for a leading multimedia company called State of Mic as she decides where to apply for graduate school. Her mother wants her to go to Canada because it can be easier for immigrants there to become citizens after graduation, and Canada’s immigration laws allow for freer travel. But Sahko hopes to return to Texas. “I hated Texas at first,” she says. “But now, I love it.”

Her first exposure to the state was big-city Dallas, so she felt disappointed at first when she got to small-town Tyler. But she came to love what she calls Tyler’s southern vibe, with people waving to each other on campus without necessarily knowing each other. It reminded her of home. “The village is where you find the most humble person, the most people who are down to earth, and that’s what I find in Texas,” Sahko says.

The Gambia was colonized by the British, so Sahko grew up speaking and learning English in school, but she learned Wolof at home. She can text and speak in the national language, but writing formally is difficult because she never had any linguistic training in school.

Sahko says that in The Gambia, many families send their children to study abroad, and even families with very limited income begin saving up early in their child’s life toward that goal. Many Gambian students feel pressured to go into STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and math—but Sahko says she her mother to thank for being able to study mass communications. Her mother never pressured her to study something she didn’t like, and Sahko is glad to be putting her mass communication degree to good use back in The Gambia for the moment.

Sahko loves to talk about her “Gambian pride,” and she says she has a burning desire to work for the health of her country. The Gambia was ruled by a dictator, Yahya Jammeh, from 1996 to 2017. According to Sahko, her family remembers those years as a bloody time. “There is no family member in our country that doesn’t have a family member that was not killed or tortured,” Sahko says.

Because of the legacies of colonization and subsequent dictatorship, The Gambia is a still-developing country. But of course, there are endless things Sahko misses about home. Sahko’s mother visited while she was at U.T. Tyler and brought with her ingredients to make many delicacies, like the gumbo-like ebbeh, the rice-and-peanut oatmeal churra gerte , as well as spice cubes and natural Gambian honey.

Sahko also talks about favorite dishes like the “one-pot” stew benachin, also called jollof. Not only is jollof a cultural staple, but it also serves as an international debate.

“It originated in The Gambia and Senegal, but the Nigerians and Ghanaians seem to think they created it,” Sahko laughs. “My tribe is Wolof. Wolof came from the Jollof empire. So whenever they try to argue with us, we’re like, ‘You do know that you’re naming our country!’”

Despite the debate surrounding food, Sahko said it’s nearly impossible to go hungry in The Gambia. “If you’re poor, everybody’s door is always open,” Sahko said. “You can just knock and just say, ‘I don’t have any food today,’ and they just feed you.”

In The Gambia, Sahko says that the population is predominantly Muslim, and that about 10 percent of the population is Christian. “You don’t even know who’s Muslim or Christian,” Sahko says. “Everybody’s so together. Everybody’s related anyways, cause it’s so small.”

After she applies to and completes graduate school, Sahko plans on returning to The Gambia again and opening her own news station, because she believes there is a need for more national news and reporting on internal affairs. But she understands why many immigrants come to the U.S. and to Texas intending to stay.

“They’re helping you more than you’re helping them,” Sahko says. “What’s the point of closing your doors when they can be open?”

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.