East Texas is a land of immense diversity. Much of the area is dominated by what is simply known as the Piney Woods ecoregion, a 54,000 square mile area shared with Louisiana, Arkansas and Oklahoma.

How can East Texans live in a healthy relationship with their natural environment, and what’s at stake when we don’t?

Our first installment in our three-part series in partnership with Deep Indigo Collective examined the Caddo relationship to East Texas ecology. Part two examined East Texas’ changed ecology with white settlers’ farmlands, enslavement of people and oil extraction.

In our third and final installment, The Tyler Loop looks at petroleum-related pollutants in East Texas, who they have harmed and what it would take to change the course.

How Tyler Became Segregated

Like most communities in the South, Jim Crow still rears his ugly head across Tyler and Texas as a whole.

Last October, Loop contributor Luke Lee authored a piece illustrating how segregation still divides Tyler. Starting in the 1930s, the city began implementing a series of city plans that divide the city along racial lines.

The city officials turned to Koch and Fowler, a Dallas-based engineering firm, to draft a new city plan. In 1928, the same firm drafted a plan for the city of Austin labeling all land east of U.S. Interstate 35 as a “Negro District.”

In 1931, Koch and Fowler began to lay out a plan for Tyler. Lee writes, “Koch and Fowler argued that although zoning laws were no longer an available option, the city could withhold municipal services to Black people everywhere in the city except for certain zones.”

Lee outlines how the firm implemented this plan. They “recommend[ed] uprooting Black neighborhoods near downtown for white development and strategically placed all ‘colored schools’ and parks to keep Black families in isolated areas of northwest, southwest and central Tyler.”

More efforts to keep Tyler segregated were implemented through the 40s and 50s. As the 1970s dawned, white people began to move out of Tyler’s center into the newer southern reaches of the city further displacing Black and other communities of color.

White flight continues today and many of the neighborhoods outlined by Koch and Fowler still exist in their segregated state.

The Poison of Petroleum

The bulk of pollutants in East Texas communities stem from petroleum related industries. Their effect is evident in rural and urban areas.

In 1982, Gibraltar Chemical Resources built a toxic-waste injection-well facility outside Winona in northeast Smith County, a predominantly Black community.

Gibraltar assured residents the plant would merely treat saltwater extracted from oil fields. On land not used for the plant, they promised to plant fruit orchards. That promise was never kept.

What they did not tell residents was the brine Gibraltar was treating contained high levels of toxins. Adding insult to injury, safety measures were not maintained. Soon after, chemicals began contaminating Winona’s land, water and air.

According to a report by the National Environmental Trust, a DC based non-profit, the state of Texas filed a civil suit against Gibraltar due to improper monitoring of the injection well in 1985. The company settled and paid an $80,000 fine.

In 1989, an additional well was constructed on the site. Due to faulty construction, a 800-foot gap in the concrete wall of the well appeared. The concrete is meant to act as a seal, preventing chemicals from seeping into the groundwater. Without the seal intact, one of the largest drinking water aquifers in the state was exposed to contamination.

Four years later, the EPA denied Gibraltar’s no-migration petition, a permit that allowed the company to continue operations. This only came after a lawsuit was filed by environmental groups in 1990.

In November 1992, the Texas Attorney General’s office sued Gibraltar in an effort for them to comply with the Texas Clean Air act. They ultimately paid $1.1 million in fines to the TCEQ.

However, this case did not establish long standing compliance. Two years later, an accident resulted in a massive hydrogen bromide leak.

Benzines, toluene and Polychlorinated biphenyl also were documented contaminants stemming from the plant.

In 1994, Gibraltar sold the facility to American Ecology Environmental Services Corporation. Under their management, the permit for the second well was reapproved in 1996 despite the gap in the well never having been properly repaired. The gap was filled with mud rather than concrete.

The EPA issued a second well permit despite their knowledge of the improper repairs, citing that Gibraltar complied with Texas’ lower standards for wells. Later, an EPA employee claimed the agency worked with the state to lower the well regulations according to the National Environmental Trust.

Later that year, American Ecology Environmental Services suspended operations, citing numerous lawsuits by residents of Winona and overall negative publicity. The company closed the facility permanently the following year.

In “Fruit of the Orchard: Environmental Justice in East Texas,” Tammy Cromer-Campell, wrote that some residents had no idea what was going on in the facility prior to the formation of Mothers Organized to Stop Environmental Sins or MOSES. They knew people were getting sick for unexplained reasons.

Phyllis Glazer moved to Winona in 1990. The next year, following an explosion at the plant, she and her son were exposed to a cloud of smoke emitted from the facility, she said.

Glazer said a few days later, “My throat and mouth felt irritated to the point that I took out my make-up mirror and opened my mouth to take a good look inside. What I saw astonished me. It looked like the roof of my mouth had melted with skin hanging down like stalactites from the ceiling of a cave. I was to find out later that these were ulcers down my throat, nose, and mouth. I also had a hole in my nasal septum.”

According to the CDC, exposure to Hydrogen Bromide can produce similar symptoms.

Included in Cromer-Cambell’s book is the testimony of another resident of Winona, Wanda Erwin. Glazer said, “Two of her sons were experiencing seizures, her youngest had stunted growth and spontaneous nose bleeds, and the family’s hair wouldn’t grow, Wanda had permanent liver and brain damage, and they all experienced headaches, body aches, and vomiting. Wanda told me that their livestock had reproduction problems and their crops didn’t grow as they had in the past.”

Lupus, stillbirth, osteoporosis, congenital conditions, and unexplained death were also frequently reported by residents.

Since the vast majority of the contamination stemmed from a lack of concern for regulations, MOSES solicited the attention of the EPA and other regulatory bodies. Other efforts by MOSES to shine light on what was happening in their community included a march down State Highway 155 to a former slave cemetery which was reportedly desecrated after Gibraltar acquired the land according to Earth Action Network.

Throughout the 14-year period of the plant’s operation, both Gibraltar and American Ecology denied the allegations against them.

In a 1995 federal district court case, Gibraltar officials contended violations to the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act were beyond the scope of the court.

Additionally, rather than address the compliance issues, they maintained Glazer and MOSES’ claims were “wholly past” the timeframe requirement of the Clean Air Act (CAA) and that they had not made repeated violations as maintained by MOSES.

The court found that MOSES had the right to appear before them, and that most of the statutes Gibraltar used to justify their case had been misinterpreted by their counsel. Despite this, the court also found that Gibraltar satisfied the regulations and declared the case moot.

According to an SEC report, another suit related to property damage claims was decided. From the earliest stages of the case, Gibraltar denied the allegations outright. The court ruled in favor of the company. Gibraltar, however, paid fines on other occasions. In 1992, they were fined $1.1 million according to Texas Monthly. In 1994 following a suit with the state, they were fined $1.5 million.

According to the Wall Street Journal, company officials seldom acknowledged any wrongdoing. Michael Stark, president of Mobley Environmental Services, acknowledged “minor and repeated incidents” in 1993, but said the necessary changes had been made.

Over 400 citations were issued to Gibraltar and AEES throughout the plant’s operation. However, these citations did not always meet their desired effect

According to the Dallas Observer, citations ranged from record keeping issues, a lack of incident reports and the manipulation of manifests documenting chemical levels.

Other issues reported included incidents where a clogged pollution filter was removed and never replaced and leaking solvent pipes. According to Brady Sassin, a lawyer told the Dallas Observer in 1998, “If these violations were ever found, nothing was ever done.”

At least 600 people filed personal-injury suits against both owners of the facility, one of which was issued by Marian Steich. Following an explosion, 600 of her chickens died and she developed skin cancer. American Ecology settled and paid $350,000 according to the Dallas Observer. Following the plant’s closure, the health of many Winona’s citizens rebounded.

Winona residents said this did not stop AEES from continuing to harass the community. Throughout the struggle, Glazer and others said they received death threats. According to Texas Monthly, in 1997, American Ecology sued Glazer, citing a conspiracy. Glazer counter-sued, claiming the suit was frivolous.

Cromer-Campell’s book says the EPA’s Civil Rights office issued an investigative report in 1997. Citing the report, Cromer-Campell writes, “The evidence in this case strongly suggests that the residents of Winona suffered repeated and acute health impacts throughout the time that the Gibraltar facility was in operation …

“The record is heavy with reports of nausea, dizziness, rashes and respiratory distress at times that coincided with odor events at the Gibraltar facility. The reported symptoms and reactions are consistent with those of chemicals known to have been present at the Gibraltar facility during the time of its operation … In addition, there is a continuing potential for exposure to residual contamination in groundwater used for drinking, due to the possibility of off-site migration of wastes.”

Twenty four years later, American Ecology still owns the former facility. A 2006 annual report published by the company stated they expect to monitor the facility until 2036.

In 2008, American Ecology applied for a post closure order, a document that outlines the final cleanup processes, with the TCEQ. It was approved the following year. According to the EPA, cleanup efforts are ongoing, but they claim human exposure and groundwater migration have been under control since 2009.

Explosions and fumes

In 1931, Taylor Refining Company was built in northeast Tyler. It was later purchased by LaGloria Oil and Gas Company and became Delek Refining in 2005. Between 1987 and 2015, the plant emitted more than 19.1 million pounds of pollutants into Tyler’s air, water and land. Some of the chemicals released include several harmful compounds, such as forms of benzene, lead, mercury, carbon monoxide and hydrogen sulfides.

The plant also had a tumultuous history.

In 2008, an explosion injured four workers. Two later lost their lives. Leading up to the incident, Delek was fined by OSHA and the Texas Commision on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) for lack of workplace safety and excess production. Fumes emitted from the fire spread into the surrounding neighborhoods, but officials did not evacuate surrounding residents.

Subsequently, the EPA sued Delek and Tyler Holding Company for its practice of illegally burning excess gases, known as flaring, and lack of pollution prevention measures. The case ultimately was settled out of court.

Other incidents have followed in the years since. In 2014, an “upset” resulted in a massive flaring episode, sending a cloud of thick black smoke across the city.

Prior to the 2008 incident, residents had lived with fumes leaking into their homes for decades. The sound of explosions and fumes were routine according to resident testimony gathered by KLTV.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, compliance violations have been routine, all of which have been considered high priority. Since 2003, Delek has been cited for hazardous air pollutants on a quarterly basis, the most recent issued on October 1, 2021.

Other violations relating to sulfur dioxide emissions date back to 2012; to carbon monoxide dating back to 2013 and 2014; and general air pollutant violations since 2019.

All of these violations fall under state jurisdiction, but remain unaddressed, according to the EPA.

Disproportionately affected

Despite the plant’s history, residential areas lie directly adjacent. The vast majority of the neighborhoods surrounding the refinery are inhabited by people of color. According to US Census data, census Tract 6 which covers the area is 90.1% minority, 69.9% of whom are Latino.

Delek, an Israeli corporation, is one of the country’s largest polluters in its home country.

The origins of this neighborhood, as others on Tyler’s north side, lie in the segregative city plans of Koch and Fowler. Many of North Tyler’s residents have grown up, raised families and worked in the shadow of this plant.

Larry Reece has lived in Tyler his entire life. He says the memories of growing up in Delek and La Gloria’s shadow still come to mind.

In our interview, Reece said a stench hung in the air. “[It was there] all the time. It was always lit up. It could be 9 to 10 o’clock and it’d be lit up like daylight.”

He said this happened two to three times a week, for up to an hour.

The effects of the plant were observed far beyond the plant directly according to Reece, who said Black Fork Creek, which flows through the facility, in the area where it crosses North Broadway “used to stink real bad.”

Reece said people knew of the refinery, but there was not a widespread effort condemning La Gloria’s actions.

“You never heard that kind of talk back then, about the air being poisoned, the water being polluted. You never heard nothing like that, and if you did, they kept it quiet,” he said.

Reece said discussion between residents and refinery management was virtually nonexistent. The only instance where any wrongdoing was mentioned by Delek was in class action lawsuits, but to Reece’s knowledge, they did not pan out.

“I hadn’t heard anything until the lawsuits, and I don’t know who got them started. To this day, I don’t know. I didn’t sign up, because to me it was more of a sham. I just don’t remember anybody getting anything financially from the lawsuit, so I figured they squashed it.

“… Maybe the people who could have said something worked there. A lot are probably dead now,” he said.

Going forward, Reece said Delek should “Get somebody to come out publicly and admit what was going on. That would be the first step… Admit y’all were wrong all these years.

“ … admit guilt, go into the community and financially do something for the people in the area. It may not affect me, but it could affect my kids.”

Reece said he is uncertain what could be done to amend environmental racism. “I don’t know what you could do. Tyler always has been bad, but they always managed to put a bandage on Tyler. I like Tyler, I wouldn’t trade it for nothing, but everybody knows there always has been that underlying stuff here.”

Reece said he sees evidence of change.

“I think the younger generation … is not so much about money or power, it’s about clean air and stuff like this. Once the old money dies, I think you’ll see a better relationship between people. The baby boomers keep this stuff going.”

“There’s a better understanding. It’s more talked about now. That is something you didn’t talk about when I was young.”

Tyler’s Delek plant and the Winona injection well site are not the only polluters in East Texas.

More violations

In between New Boston and Texarkana, the Lone Star army ammunition plant has been a significant violator of the Clean Water Act, according to the EPA.

From 2018 to 2019, violations occurred on a quarterly basis. Violations also were found in July of 2019 but were resolved.

Most recently, violations were recorded in April 2020, and the EPA has not determined if they have been resolved. Most formal violations have stemmed from aluminum contamination of several water bodies on site. Additionally, mercury and lead compounds have been detected.

Another former military installation, Longhorn Army Ammunition Plant in Karnack, now Caddo Lake National Wildlife Refuge, has a history of contamination. On Aug. 29, 1990, the EPA placed the area on the National Priorities list.

Cleanup activities are ongoing and several areas on the refuge are closed to the public due to contamination or unexploded ordnance.

At this point, the EPA says human exposure is under control. However, they said there is insufficient data to determine whether chemicals are continuing to seep into the groundwater.

The predominantly Black community of Karnack lies directly adjacent to the refuge and could be exposed to chemicals if groundwater migration is not under control. Additionally, contaminants could be seeping into nearby Caddo Lake, which has been designated as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention since 1971.

In addition to potential human hazards in Karnack, the immense diversity of Caddo Lake’s flora and fauna is under threat. The flooded cypress forest, the largest of its kind in the world, is home to 216 species of bird, 47 mammals and more than 90 species of fish.

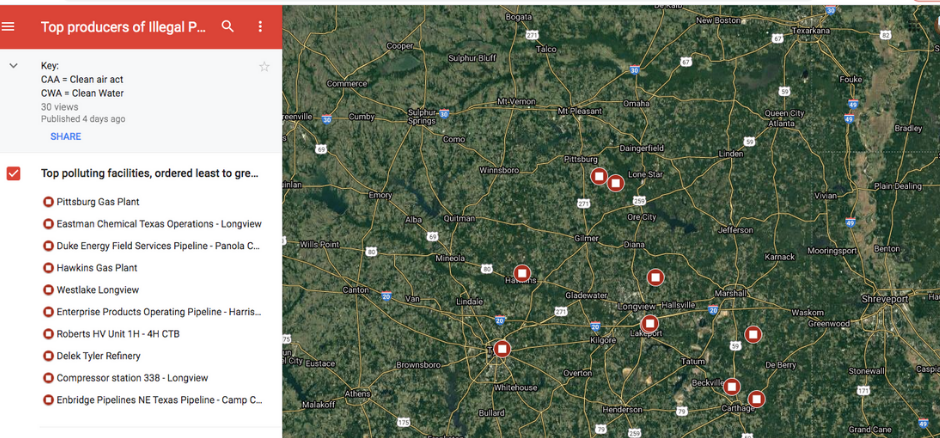

Other sources of pollution are spread across East Texas. According to a report by Environment Texas, Delek’s Tyler refinery produces the eighth most illegal air pollution in TCEQ region 5, which covers Northeast Texas.

The climate change factor

Concerning environmental hazards, climate change poses an ever-looming risk globally and of course, in East Texas.

According to a climate assessment conducted by Texas A&M University, Texas’ average temperatures could rise .6 degrees Fahrenheit per decade.

As for East Texas, the southernmost counties have experienced an increase of just under one degree Fahrenheit, while most of the northern and central counties have seen a spike similar to the state average of .6 degrees Fahrenheit.

Between 1898 and 2020, average precipitation per year has increased in East Texas, with the northeast increasing 2 to 1.5 inches per year. East Texas’ central counties have experienced between 1 and 1.5 inches, while most southern counties have seen an excess of 2 or more inches.

Extreme flooding events, winter storms and tropical systems also have increased in frequency and severity in recent years.

Many of these severe events will have the most profound effect on communities of color.

In February, power outages caused by winter storm Uri disproportionately affected marginalized communities across the state, according to the Washington Post.

In the wake of Hurricane Harvey in 2017, low income communities of color bore the brunt of flooding in Houston, according to an article published by the University of Texas School of Law.

Harvey’s effects also were felt in East Texas, with flooding striking the predominantly Black cities of Beaumont and Port Arthur.

Disaster-related damages from Harvey widened the wealth gap between Black and white people to $87,000 on average, according to a study by Rice University, the University of Pittsburgh and FEMA.

Layers of threats to non-white communities are compounded due to outdated infrastructure, according to Colombia University’s School of Climate.

Turning the tide against pollution and climate change

East Texas holds a prime example of communities resisting corporate contamination. Citizens of Port Arthur organized the Port Arthur Community Action Network (PACAN) aimed at addressing pollution stemming from the city’s Oxbow Corporation Industrial Plant.

The plant, owned by billionaire Bill Koch has leaked 22 million pounds of sulfur dioxide from 2016 to 2019, according to Nation of Change. Bill Koch’s brothers, Charles Koch and David Koch, have been notorious spreaders of climate disinformation, according to DeSmog.

Community organizers say the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality has allowed the facility to operate without scrubbers, equipment designed to limit emission of gasses like sulfur dioxide. Few plants in the state operate without scrubbers.

Last summer, PACAN and its legal council gained the attention of the EPA. As they requested, the EPA’s Civil Rights Compliance Office has launched an investigation into whether the TCEQ is violating the Civil Rights act.

Founded in 2018, PACAN calls attention to other issues plaguing their community such as flooding concerns and other industrial plants in the area.

Additionally, Texas based groups like Environment Texas have sought solutions to pollution, environmental racism and climate change.

Environment Texas has been active in preserving habitats across the state including in East Texas. In 2006, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the Texas Conservation fund worked in tandem to establish the Neches River National Wildlife Refuge, blocking efforts to impound the river for a reservoir.

This sector of the Neches is still lined with old-growth bottomland hardwood forests essential to countless migratory species of birds and mitigating floods, according to Environment Texas.

According to ScienceNews, protecting stands of existing forest is the first step to take in fighting climate change. Additionally, responsibly planting more trees may buy time to further develop carbon capturing techniques.

Caring for the land means caring for people

In the first issue of this series, the traditions of the indigenous peoples of East Texas were discussed.

Chase Kawinhut Earles, an artist and member of the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, mentioned his people’s stories and traditions.

“We’re not an archaeological artifact, we’re still here … Our people still know all of our songs and dances … We still have our culture and art. We’re not the biggest tribe, but we still hold our traditions.”

Earles’ statements about the Caddo flood story are appropriate in closing.

“The droughts caused the lakes and rivers to dry up, and so immediately we thought we had done something wrong. It kind of reflects for us how what we do is reflected in what happens to the earth and our environment …

“…We felt like we were treating people wrong, we were treating the animals wrong, so that’s why everything dried up.”

In the face of pollution and our changing climate, these words provide pause and wisdom for the future.

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.