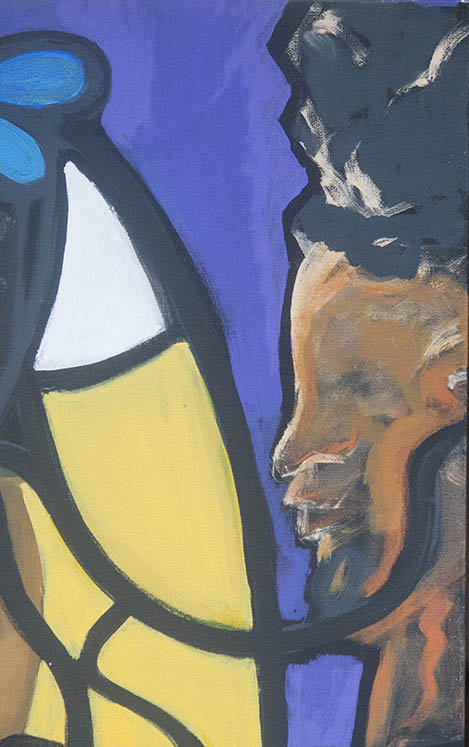

In a background of royal purple and optimistic yellow hues, the faces of four ancestors bear witness and guard over a queen mother and child who are bound together by flowing locks of hair. They are cradled by the loving hands of a mother, whose hands also represent those of God. The acrylic painting by 28-year-old Tyler artist Daryll Phillips (moniker DPhillGood) is aptly named “Protected”.

“Protected” is Phillips’ response to mounting raw emotions in the spring and summer of 2020 as violence and police killings of Black Americans gained national attention.

His painting contains elements of afrofuturism, an art movement including science fiction or futuristic elements alongside Black culture and history. Afrofuturism featured prominently in the art and architecture of the 2018 blockbuster movie “Black Panther”.

On Nov. 25, the DPhillGood Instagram account posted a video with Phillips explaining the painting.

“This piece was inspired by when Breonna Taylor got killed, and I saw the outcry of so many people worried about their lives, their well-being and their safety in this world,” Phillips said.

The post described frustration with people who felt scared to be Black in America. He said that people need to be aware of their surroundings, but they don’t have to live in fear.

“I felt for my people. I finally got fed up enough to paint about it,” he said.

As reports of violence against Black people rolled in, Phillips thought of the women closest to him: his sister, fiancée and mother. “They don’t feel safe for their daughters being in this world,” he said.

In addition to afrofuturism, Phillips’ personal life, background in the Christian church and studies of spirituality come into his piece.

As he was finishing the painting, Phillips himself was about to become the father of a Black child. “I made this piece, I basically completed it — it was crazy — the night before my daughter was born.”

One of Phillips’ earliest memories is of being at church with his grandfather, the late Reverend Leotha McGee, at Greater Hopewell Baptist Church. His mother, Merlyn Phillips, is now the pastor of Family Way Missionary Baptist Church, where Phillips plays keyboard.

While working on “Protected,” Phillips did not consciously include church symbolism, but he noticed upon completion that the painting had a stained glass cathedral effect.

Phillips attributes the role of God in his creative process. He often begins a painting feeling the strokes of his paintbrush are being guided. The four faces surrounding the mother and child in “Protected” were an unplanned addition to the piece. “My paintbrush just started moving and these faces came,” Phillips said.

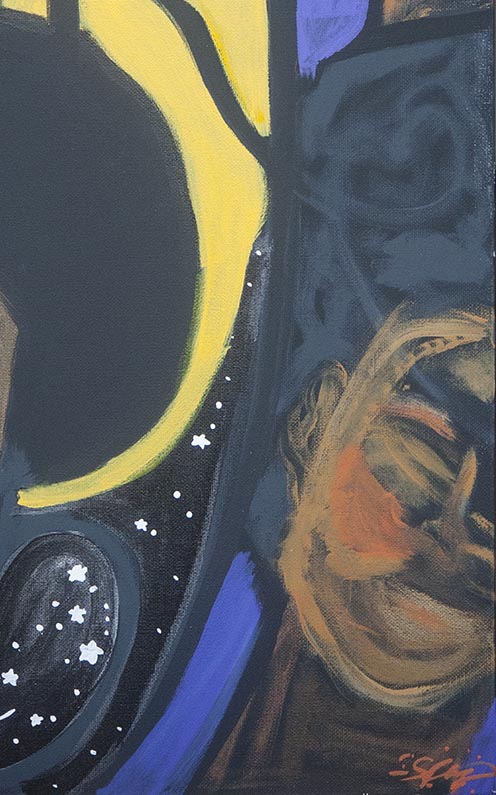

Hands holding the child are as dark as the night sky and detailed with stars. “Stars are what we’re made up of, we are the same as the galaxy — we are unlimited, we are eternal,” Phillips said. “When you look up at the stars in the sky, that’s you.”

The faces are somewhat androgynous with brusque and unfinished brushstrokes.

Phillips says the faces represent spirit guides or ancestors who have passed away. “These are entities and spirits that lead you, guide you and speak to you and let you know that you are not alone.”

The mother’s hair and headpiece contains the seven colors of the chakras, seven energy centers within the body.

“When I painted this, it kind of just happened,” Phillips said, “I was thinking about enlightenment. I wanted it to be a conversation piece when I put it on the painting, for people to ask questions about it and to learn about chakras, the levels of enlightenment and who we are, how we evolve through these dimensions.”

Phillips’ interest in chakras and levels of enlightenment rose after studying various polarities in life such as masculine/feminine energy; dark/light; and hot/cold.

Surrounding the chakras in the mother’s hair is a large, single eyeball.

“The eye is in a lot of my work,” Phillips said. “There’s just something about an eye that makes me feel safe; it makes me feel insightful.”

In this particular painting, the eye takes on the role of a protector. “When your eye is open you see things more for what they are versus what you’re being fed. You can actually see the truth, and that’s one of the messages of this painting,” he said. “See beyond what you’re being shown on the surface when it comes to Black people being killed and people being killed in general.”

Phillips says the yellow surrounding the mother and child represents sun and fire elements. Yellow also represents the solar plexus chakra, located behind the abdomen. Meanings associated with the solar plexus include self-power, self-esteem, intellect, decision making and beliefs. It’s an apt color to surround the mother as she eschews feelings of fear and powerlessness.

“That light around them is protection; it’s self-love,” Phillips said.

He also sees the oblong yellow object as a pod-like vehicle to a more positive state of being.

Reflecting on the message of afrofuturism, Phillips explains it like this: “Your spirit energy outside your body is like a spaceship that can transcend dimensions.”

In the podcast Skeleton Keys, which “unlocks the mysteries of mythology and history in pop culture,” hosts Torri Yates-Orr and John Bucher expound on the genre in the “AfroFuturism” episode. “You can go as far back as Egypt and Nubia, being connected to astrology,” said Yates-Orr. “This is a long history of being connected to the stars and the planets. It allows us to create a future where you’re not having to live in a society that’s racist or that tells you you can’t do anything.”

Similarly, Phillips’ “Protected” combines futuristic images with Black ancestral support, spirituality and empowerment. The spaceship becomes a medium to surpass and rise above current realities.

Additionally, Phillips’ piece conveys a specific message to those facing racially charged violence and dangers.

“We know that racism is a real problem, we know there are a lot of problems in the world, but to not live in fear was my message with this painting.”

View more of Phillips’s work at https://www.instagram.com/dphillgood/

Sarah A. Miller is an independent editorial photographer and journalist with over 10 years of experience in newsrooms across the country. She lives in Tyler with several roommates and three quirky cats. Sarah loves being a community storyteller and getting to document the everyday lives of people in East Texas.

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.