Kawsar Yasin is the kind of adolescent middle-aged adults like me love: quick to smile, holding her own in conversation, unassuming and respectful.

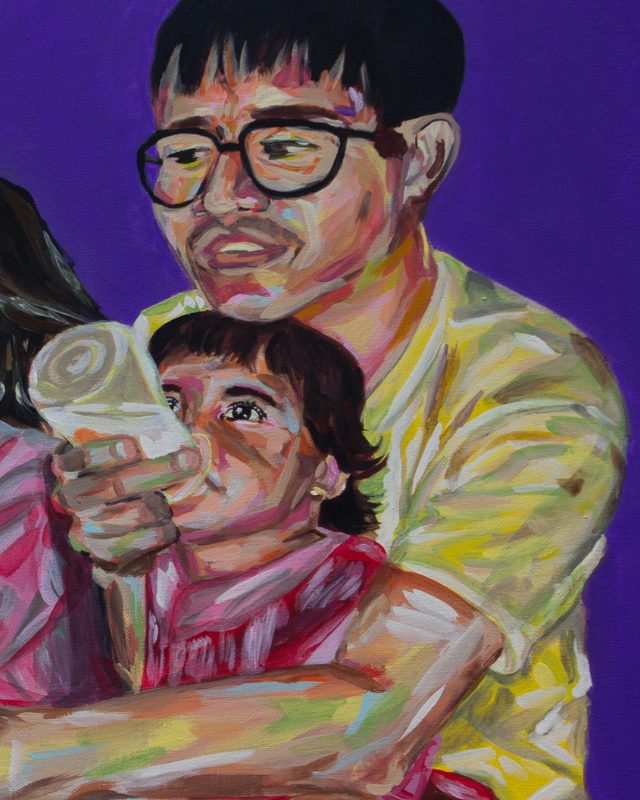

As we talked about her acrylic painting, “Weten,” I found more to love. A first-generation American with ties to China’s Uyghur region, Yasin’s painting contains multiple meanings of home and family.

Yasin’s painting skills accelerated last summer with plenty of time at home and this year in her art class at Legacy High School. “The summer before my sophomore year of high school, I was just really bored. I think I binged the entire Marvel cinematic universe while painting,” said Yasin. “I had a ton of canvases lying around, so I just tried it out and really liked it.”

Back in school her junior year, Yasin discovered a style she used in her painting, “Weten.” “I took AP (Advanced Placement) studio art and delved into pointillism, where you just use random dots of color. The farther you step back, it blends together, but you don’t blend the actual color.”

Yasin explained the photo inspiration for “Weten” and the story behind it, revealing her dad’s sense of humor. “This is a portrait of a little moment my mother captured with an old camera over 10 years ago.

She said the photo from 2009 marked a chaotic era in her family as her parents raised three young daughters in Denton, Texas. “It was staged because my dad was just joking around saying how busy of a father he is, feeding two girls [at the same time]. My dad was like, ‘Hey, take a picture of me showing how busy I look trying to feed two kids.’”

Yasin, age six in the photo, is holding a glass of water to blend in with her sisters. “I tried to make it look like a bottle, but it was a glass of water. I think I just wanted to be in the picture with my two sisters getting fed,” said Yasin.

Years later, Yasin felt nostalgic about the photo. “It was a really fond memory I had. Growing up, I think we had a very close connection with each other.

“In my mother tongue, Uyghur, “weten” means homeland,” said Yasin.

And the reason [my painting is] titled “Weten” is because I wanted to show the immigrant value of family. My parents immigrated to this country and they only had each other, especially since we were such a minority anyway.”

Because other Uyghur families were few and far between in Texas, Yasin said her parents became her source to understand Uyghur culture. “We didn’t really have much of a community here. When my parents started a family, they started becoming this community. Our ethnic enclave is just our family in a sense.”

As Yasin began her painting, the idea to experiment with color emerged. “At first, I wanted this to be a realistic painting. I put in a lot of purples and dark reds, then yellows and greens for the highlights. I realized I may not want this to look realistic, actually.”

As Yasin painted, the colors took new meaning. “I came to realize the pops of color here and there show the chaos and how colorful an immigrant family is in the United States.”

Yasin said her parents transmitted their origins in China’s western Xingjiang region to their children through Uyghur language, music, stories and nursery rhymes. Food also played a role.

“As Muslims we celebrate Eid twice a year. We have our own distinct elements to it. Every evening we would make this crunchy dough called sanza,” she said.

The title of Yasin’s painting means more than just homeland. Weten is also the informal way of saying East Turkestan. “Since I’ve never been to our home country or home state, I come from my family.”

Although Yasin’s parents have transmitted Uyghur culture to her, she says there are gaps in her knowledge. “I definitely know more about U.S. and world history but not my own people’s history. That is a result of me living here and not ever going back to our home place,” Yasin said.

Yasin said she struggled to share her family’s origins with her Texas peers. “Until recently, not many people knew of our culture because of the political situation there. Whenever I was in elementary school, I wouldn’t know how to explain I’m from East Turkestan. I’d often tell them, ‘I’m Turkish’ or ‘I’m Mongolian’ or something like that. I didn’t want to explain myself.”

An incident in her world history class changed Yasin’s decision about disclosing her identity. “[It was] during a lesson on The Turkish-Armenian genocide. Since I told a lot of people I was Turkish, everyone was just looking at me awkwardly,” she said.

“The end of the class period, my teacher pulled me aside. So I told him the truth about my identity. This was actually the day before quarantine. The last thing he said to me was, ‘Don’t be afraid of who you are, and don’t be afraid to tell people who you are.’”

Yasin took the words as a personal reflection and challenge during the rest of the school year from home. “I’ve thought about that incident for such a long time. Why am I telling people that I’m Turkish or Mongolian? I became more confident to say, ‘I’m from East Turkestan.’”

Yasin says news reports about Uyghur persecution have helped her peers better understand her roots. “We’ve always known what’s been happening simply because we would often talk to my relatives via WeChat up until 2016 or 2017. That was when we heard of family members ‘going to school.’ That’s like a red flag, that’s basically code for detained.”

Yasin said the news of Uyghur detainment has intensified her feelings reflected in “Weten.” “It made this painting even more important to me. We’re losing our roots, so all we have here is each other.”

As for artists she appreciates, Yasin says Instagram is a source for inspiration. “I started looking at Instagram artists like Sari Shyack from Austin. Actually, it was this meme she painted of a Bratz doll. She didn’t blend everything and everything looks so geometric, even though she didn’t create an outline before.”

Yasin said the central theme of family in “Weten” is clear, but its other meanings may be missed by viewers. “Everyone who’s seen it, I don’t think they’ve recognized the much deeper meaning behind it. They oftentimes ignore the inner struggle [immigrants] may have being cut off from their culture, and the vibrant culture they hold within.”

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.