The Tyler Loop is sharing stories of young undocumented East Texans who are nervous about Texas’s new attack on DACA, the program that allows them to work legally in the U.S., and about SB-4, the new Texas law that requires local police to act more like immigration agents. Read more about this project here.

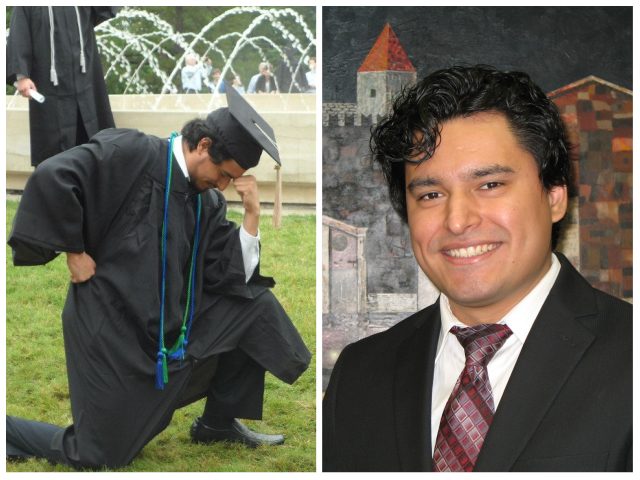

Johnnatan is 28 years old and first came to Tyler when he was thirteen. He went to middle and high school here, and to U.T. Tyler for college and a master’s degree in Business Administration. Today, he works at an insurance company in Dallas and is applying for residency through his wife, who is a U.S. citizen. That’s not a quick process, though, and in the meantime, if DACA were to be suspended, he could lose the ability to work legally. He also explains why the rest of his family hasn’t gotten close to becoming legal citizens yet. He’s a sharp, funny, deeply earnest guy, and you’ll never meet an insurance salesman so fervently enamored with his job. This is Johnnatan’s story.

“I had graduated from U.T. Tyler with a bachelors in marketing when DACA came out in 2012. I immediately applied through a lawyer. I didn’t want to take a chance and do it myself to save money, but end up doing it wrong.

It was hard to come up with the money for a lawyer. We are not a wealthy family. My dad was making $500 dollars a week, and we were living below the poverty level. My mom ended up selling her jewelry from Mexico to pay for it. She had very nice gold bracelets; in Mexico, my parents were well off. Mom had been a very successful saleswoman for a Japanese probiotic company. But we came to the States so my brother and I could speak English and do well, and because my dad was already coming here for work and my mom was tired of being apart from him.

She never wanted to sell her bracelets. They were very nice. But she had to sell them all. I feel so bad about that, and one day I will repay her. She said, “This sacrifice today will yield fruit in the future. You guys are my everything.”

And sure enough, when I was able to get a social security number thanks to DACA, it changed everything. I started applying for small loans to build credit. Within six months I had built enough credit to buy my first automobile, through a dealership no less. It was $4,200 for that vehicle loan, but I was able to get what I wanted: a ‘99 RAV4. The moment I got that car, I became, for the first time, an independent adult.

I came to the U.S. in December of 2003. I was 13 at the time, and I started the spring semester of 8th grade in Tyler, at Moore. I didn’t speak any English at the time. They asked me, “Do you want to be in band? It’s a little late, but you can try.” I was like, “You know what, let me learn how to read English first, then maybe later I’ll learn to read music.” It was a fantastic school.

I learned what it meant to not be an American citizen, and to be labeled as illegal, during junior or senior year of high school, when I started applying for college scholarships. All of the applications needed a social security number. It was heartbreaking that everywhere I would go, doors were shut in my face. I just didn’t have the money without those scholarships.

As for which college, under Texas law I could go anywhere in-state without a social security number. But I was contemplating being an architect, and I wanted to go to Mississippi State, where they have a really fantastic program. As soon as I told them I didn’t have a social, they said, “You need one in order to go here. We’re so sorry.” I felt like a bird in cage. I had the capability to fly very, very far, but I just couldn’t because I was held back by that cage. But eventually I found a scholarship that didn’t require a social security number, and I ended up in a different career that I love thanks to my marketing degree from UTT.

Here’s what I say to someone who thinks I shouldn’t be able to live or work in the U.S.: Do you want Social Security when you reach retirement? If so, you need as many people as possible paying taxes. [It’s estimated that undocumented immigrants pay billions of dollars a year to Social Security deducted from their wages, which they will never benefit from under current law.]

Or take sales tax. You pay sales tax whether you’re legal or illegal. If people like me were to be deported, tax revenues will go down. That money is used for federal and state programs that benefit those who are legal as well. It helps to patch potholes on the streets. It pays for infrastructure.

The same with local spending. We go to restaurants, we buy cars, buy homes, purchase local products. That’s why deporting people like me is bad math, because honestly, you will end up screwing your local economy. I don’t want to take anything away from anyone. I just want to contribute, be a law abiding citizen, and live in peace. I will pay whatever you want me to in order to become a citizen.

Yes, there are immigrants who are criminals and should be deported, but the bad apples should not define all of us. Bad apples come from everywhere. I don’t think people hear this very often, but for immigrants like me who are trying to become legal, we know we have to act like angels because even minor mistakes could ruin your chances. You have to be much more careful than the average citizen.

I’ve tried to change people’s minds about the process for becoming a citizen, because they think it’s so easy. They say, “If you’ve been here all these years, why hasn’t your family become citizens?” If they’re willing to listen, I explain that after we came here, my dad tried to apply through his brother, who is a citizen. That process takes fifteen years. My dad still has six years to go before he will be considered for an interview with a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services agent.

When we moved here, my brother and I were young enough that we could be part of my father’s application. The process takes so long, and when we reached adulthood we were too old for that. A lawyer once told me the only way to become legal was either wait for the law to change and hope for amnesty, or marry an American woman. A lawyer told me that!

I actually did end up meeting and marrying a U.S. citizen, and shortly after my wife and I got married, I applied for residency and change of status through her. It takes about a year. I have submitted all my paperwork, and now I just need to meet with a U.S.C.I.S. officer so they can make sure my marriage is not fraudulent. Shortly after that interview, I should get the green card. But of course, not everyone will marry someone who happens to be a U.S. citizen.

When I explain all this, people say, “That’s messed up. No wonder you can’t get legal citizenship quickly.” I say, “Exactly.” It’s not that people don’t want to get citizenship legally. They do. If they had citizenship, they could travel the world. They could go to visit Mexico. [Undocumented residents can’t apply for passports. If they leave the country, they may not be able to get back in.]

I’m an account executive for a commercial insurance company in Dallas. I love it. I do my best to help people understand a product that is highly misunderstood. Insurance is not tangible. You can’t feel it, can’t see it, can’t smell it. It’s very disconcerting, so I do my best to explain and to find you the most economical quote you can get.

I never saw myself doing this. No kid thinks, “I want to be an insurance agent when I grow up.” It’s a highly misunderstood industry. I know people say insurance is a necessary evil. The way I see it, it makes you responsible to the public. If you have a homeowner’s policy, and someone comes into your house, and slips and falls, then has a seizure, your policy helps you manage that responsibility. You owe people a level of safety when you invite them into your home.

The reason I got this job and into this industry all started two months after I got DACA, when I was in grad school and was working for my dad and my uncle to make money. One day I was helping them paint the house of a man who happened to be the C.E.O. of an insurance company. I was painting the flowerbeds. The man came home, and my dad says to me, “Johnnatan, he’s the C.E.O. of his own company, you should ask him for a job.” Surely not, I thought. I was only in the first year of my master’s degree, and there I am, with my shirt and pants covered in paint. But I’m a Christian, and I thought, this could be a godsend for me.

I was very embarrassed when I went to go talk to the man. I said, “Excuse me, I hear you’re the C.E.O. of your own company. Do you by any chance hire poor recently graduated college kids?” He kind of laughed and said, “Well, we hire all the time.” He gave me his card, and I polished my resume all night so I could send it to him in the morning. I didn’t hear back until four weeks later, when the president of the company called me and said he got my resume from the C.E.O, and he wanted to talk to me about an internship opportunity.

I didn’t know anything about what the company did. I didn’t know anything about insurance. I was just excited to be getting a job. I went into the office and talked with him for three hours about history and different things. We just kicked it off. At the end of the interview, the president said it was a done deal. I said “Yes, this is awesome!” I started work the following week.

A few weeks after that, the president learned that my mom was driving me back and forth to work each day, which was very stressful for her. I couldn’t afford a car at the time, and my credit was still very new. The president said, “Well, we need to fix that.” I was just an intern, and he was literally the president. He took me to a local credit union, where he’s a member of the board, and told them, “Try and do the best you can to help this young man out.” With his help, I was able to get the loan to pay for that little RAV 4, and that changed my life right away. Suddenly, I could go anywhere. The president is retired today, but he still mentors young account executives like me. I love that man.

I understand that some Americans feel their laws and country are being taken advantage of because someone like me can come here and accomplish things they can’t, or aren’t. But it’s not that we want to violate the country or the law. We’re just trying to get a better future. This is the land of opportunity, the American Dream, and that’s why we come. My only crime was I came here with my mom when I was too young to make decisions on my own. (I’m not blaming my mom, of course.)

What would going back to Mexico look like, if for some reason my green card didn’t happen, or for my brother, who also has DACA and isn’t married to a U.S. citizen? It’s very scary. I have seen interviews with people who were forced to go back, who are in their 40s or older, and they haven’t been in country for 15 years. They’re starting from scratch. They don’t know what to do. Mexico is still their country, but the country has changed. How do you register to vote? How do the roads work? How do you get a driver’s license? Even though it’s my place of origin, Mexico is a foreign country to me. I’ve never gone back to Mexico, because there was no guarantee I could return. The U.S. is my home. I don’t want to be a burden on anyone.

I’m a huge Star Wars fan, and so I just try to bring people to the light side of the force by explaining, to anyone who will listen, how citizenship really works in this country, and the economic benefits of people like me being here. You might not want me here, but are you sure you understand what it would do to your life and your economy if everyone like me had to leave? Instead of kicking us out, allow us to pay back taxes or whatever else. I would pay it. I would do what it takes.”

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.