After more than a year of the COVID-19 pandemic, Texans are finally getting a taste of freedom thanks to widening access to vaccinations, but the road to an immune Texas is not straightforward just yet.

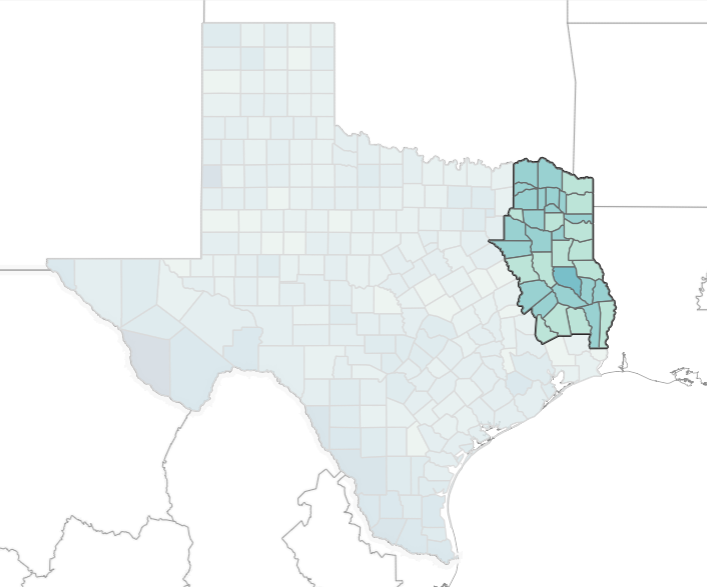

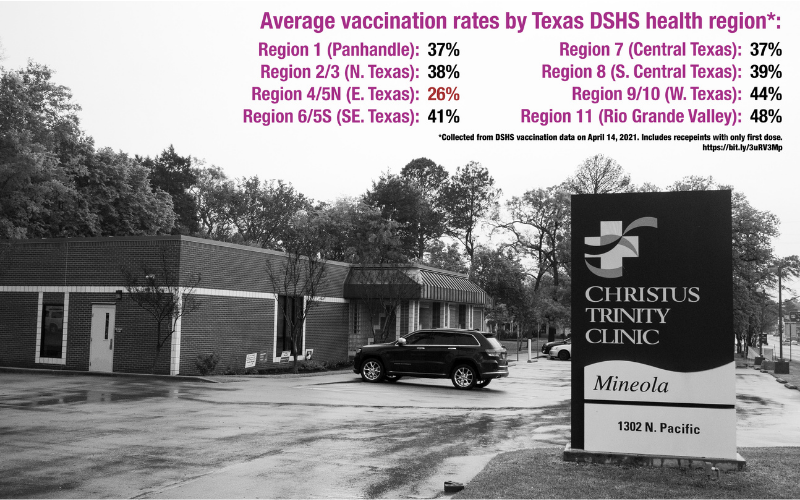

Texas has vaccinated 45% of its population with at least one dose, around 40% shy of the CDC’s recommended level to achieve national herd immunity and prevent further spread of COVID. However, distribution rates are not evenly spread across Texas, and Department of State Health Services (DSHS) data shows some areas of the state may take longer to reach CDC goals.

Of the 11 DSHS public health administrative regions overseeing counties across Texas, Regions 4 and 5 North (4/5N), which comprise 35 East Texas counties, show the slowest progress in vaccinating their population, according to DSHS county data.

The region covers over 1.2 million people in mostly rural areas and extends from the easter Red River basin to counties just shy of the Gulf Coast. DSHS lumps together regions 4 and 5 and data and services according to their shared headquarters in Tyler, the region’s largest city.

As of April 14, Region 4/5N had an average vaccination rate of 26% — the slowest of any state health region. Other very rural areas, such as the Rio Grande Valley and far West Texas, had 48% and 44%, respectively.

The regional difference in vaccine rates indicate lurking issues affecting public health for people of the East Texas region, including lacking access to health education and literacy.

The state’s allocation strategy initially favored population centers and vaccine hubs in the first months of vaccine distribution, requiring East Texans from sparsely populated areas to travel farther for vaccines.

Vaccine supply and allocations expanded to penetrate more East Texas counties by late March, but local health experts suspect misinformation and anxiety about vaccines will continue to depress immunization rates.

A rocky start

Beginning with the first rounds of vaccine distribution in December, East Texas hospitals and public health authorities helped establish several main vaccine hubs to deliver a majority of doses in Tyler, Longview and later in Texarkana.

Although situated in some of the most populated East Texas cities, many residents in region 4/5N would need to drive several hours to reach them, adding to the importance of more rural clinics as secondary distribution sites.

Family clinics, private practice offices, pharmacies and dozens of grocery stores make up a majority of East Texas’s vaccine clinics in towns without hubs or hospitals.

“We’ve had people travel some very long distances to get to vaccine hubs and our clinics to get a vaccine,” Dr. Mark Anderson, chief of emergency medicine for Christus hospitals, said. “They’re signing up from all over the state and searching online… We have hubs that do serve rural areas too because people can drive several hours to get there. By distributing to our clinics, when we have the Moderna in particular, we can distribute to those rural areas.

So far, smaller clinics have seen slow progress with state vaccine allocations.

“We’ve had a couple allocations at some of our smaller, more rural facilities,” Dr. Thomas Cummins, chief medical officer for UT Health East Texas, said. “The problem is keeping a steady supply. The state has focused on places that give large numbers of doses pretty quickly, but we’ve got doses coming into some of our smaller facilities. We’re building out plans to give them, and we’ll see how quickly they do give them.”

Cummins and Anderson said their rural and secondary clinics are often limited on the quantity and type of doses they can handle due to the freezer capacity needed to store vaccines. Most rural clinics receive more Moderna or Johnson & Johnson doses because they can be kept at regular refrigerator temperatures for longer amounts of time than Pfizer vaccines, which require far colder temperatures than standard freezers.

When clinics do apply for vaccine doses, there is often no clear timeline or communication for if and when the state may send allocations.

After making initial requests for vaccines in the fall, clinic managers at Paris Family Physicians in Paris, Texas were left wondering about potential allocations for weeks while the state sent vaccines to other areas in Lamar county.

“In the beginning you didn’t hear anything, you just wondered if your allocation was submitted properly,” Laura Rast, practicing administrator for Paris Family Physicians, said. “We had no way of knowing. But then they did begin sending emails after you’d submit weekly allocation requests. Later on in the week, they’d send an email for your allocation request from the previous week saying ‘Sorry, you didn’t get it.’”

The clinic received 100 doses of vaccines on March 1, after a Paris hub received a majority of the county’s doses and tamped down local demand. Rast said the state process for allocations does not send out notifications for fulfilled requests, but only for denials.

An uphill battle

Though vaccine allocations have ramped up, East Texas continues to lag behind, and herd immunity remains a distant goal.

At the Sabine County Hospital in Hemphill, Texas, home to almost 11,000 East Texans near the Louisiana border, vaccine allocations came in but patient demand for vaccines have lagged behind.

As state allocations ramp up vaccine supply across Texas, East Texas hospital administrators and state rural health advocates warn of a different barrier to vaccine distribution: education.

“The issue in our area is not getting the vaccine. We’ve got it here,” Jerry Howell, Sabine County Hospital administrator, said. “Even with the flu, and even though the flu vaccine has been around, there’s not a majority of people that get the flu vaccine. I think that getting the [COVID vaccine] out now is not really the issue. It’s how many people are going to take it.”

Howell attributed some of the anxiety surrounding COVID vaccines in East Texas to partisan influence and misinformation shared on social media, mostly among people with right-leaning beliefs. Conservative politics dominate the region in congressional and presidential elections, with some portions of Sabine county casting over 80% of their votes for President Trump in the 2020 election – not unlike most other East Texas counties.

Some conservative voices in East Texas have contributed to false narratives and paranoia surrounding vaccines, including U.S. Rep. Lance Gooden and Tyler bishop Joseph Strickland.

Strickland made headlines in January after making a tweet claiming vaccine production involved “murdered children” and fetal tissue, in reference to stem cell research that enabled COVID vaccine development.

Last December, Gooden, a Republican representing western counties in Region 4/5N, falsely implied that the federal government would create a registry of all vaccinated people for contact tracing.

Public opinion polling from January by COVID Collaborative, a joint effort to study COVID by multiple national institutions, found Republicans and people in rural areas expressed more hesitancy about taking a vaccine, with 58% of Republican respondents expressing their intention to take the vaccine, compared to 83% of Democrats.

Less than two thirds of rural respondents intended to take a vaccine, while 72% of urban and 73% of suburban respondents reported they would receive a dose.

Hesitancy about taking vaccines has even affected healthcare workers within Howell’s hospital, where 50% of staff has yet to be vaccinated. UT Health administrators experienced similar attitudes at their facilities in Tyler.

“People who work in healthcare are as influenced by social media and [politics] as others,” Cummins said. “There are still a number of myths floating around in social media about the vaccine, like it distorts your DNA or makes you infertile, or Bill Gates is going to use it for mind-control. There’s some really ludicrous stuff out there, and then there’s some general ‘It was developed so quickly, I’m not sure I trust it or believe in it.’”

Howell and other East Texas workers said they often face an uphill battle with educating people about vaccines and publicizing available doses, partly due to lacking access to local news and information. Their efforts to expand clinic hours and events still need publicity to draw patrons.

“It’s really hard to market in a small town,” Howell said. “We don’t have a TV station. We have an online newspaper we can get an ad in, and then there is a print paper, but you have to send content a week ahead. When we weren’t getting vaccines, we never knew when we were going to do that.”

Leading by example

Without more trust in COVID vaccines, experts warn the state risks missing the 94% immunity rate the CDC says will stop transmission. Under 40% of Texans are vaccinated as of April, 12, but some Region 4/5N counties have a vaccination rate around 15%.

“The thing I’ve started worrying about among these that are telling me they’re wrapping up, is when you look at the state [data] by region, there’s still only a third to a half vaccinated,” John Henderson, CEO of the Texas Organization of Rural and Community Hospitals, said. “That’s just not nearly enough to get us to where we need to be. This whole issue of reluctance is improving, but not as fast as supply is improving. And we are nowhere near herd immunity.”

Rural hospitals and medical practices could serve as a key component in resolving some Texans’ trust issues with COVID vaccines through leading by example, Henderson said, a sentiment echoed by Howell in Sabine. Seeing neighbors and friends take the vaccine and help dispel rumors could encourage doubters to get their doses.

“When rural primary care physicians, in particular, say ‘Not only do I recommend this, but I’m doing it myself, and we’d love to vaccinate you,’ that probably goes further than anything [TORCH] could do,” Henderson said.

“I think we’re on the right track now, but we got to do a lot more.”

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.