Every day, something triggers me. I am constantly fighting off the lingering psychological side effects of spending 19 years in prison. Anything from the sound of jingling keys to people arguing at the grocery store revives buried memories of incarceration. When this happens, an overpowering anxiety threatens to mentally and emotionally drag me back to those cages. I must stop whatever I’m doing, take several deep breaths and ground myself with affirmations about the present moment.

In the two years that I’ve been home, I’ve been able to successfully slip from the grip of those terrible memories. That is, until the recent winter storm.

When I woke up Wednesday, February 17th and realized that I was without running water, panic finally took over. I heard a familiar hollow gargle in the bathroom sink. Suddenly, I could smell the stench and filth of five backed-up toilets in a shared, small space with 30 other women.

I could feel our humiliation and our desperate thirst. I steadied myself against the counter, as I was somehow both there and back in prison. I paced in between the bathroom and kitchen, frantically checking the sinks. I put the toilet lid down and left a note for my roommate, who is also formerly incarcerated. “Don’t freak out but there’s NO WATER!”

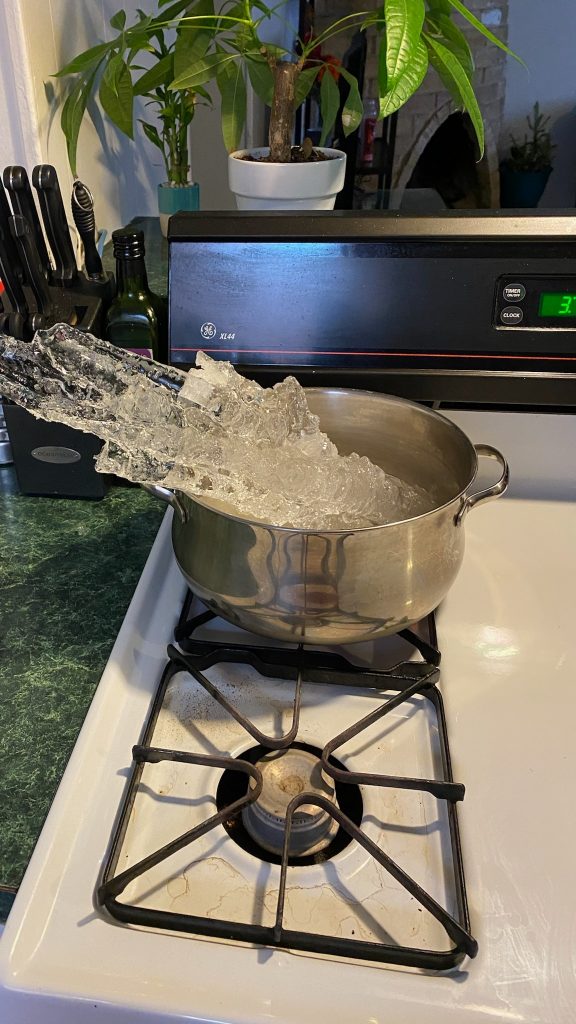

Without power and water, cold and trapped inside, the terror of prison gripped us again. We went into survival mode with a touch of irrationality and paranoia. We spent hours filling every bucket, tub, bowl and pan we could find with snow. I kept checking the outside gate to our house at night to make sure it was locked, fearful that someone would come and steal our containers of snow. We were obsessed with making sure we had water.

We made it through with our sanity intact, but our severe anxiety was a constant reminder and evidence of the reality of living conditions in Texas prisons and jails.

The squalor in which incarcerated people are forced to live is amplified in times of crisis, but these poor conditions exist every day. The panic I felt in my bathroom when I realized the water was off didn’t happen because I had one or two experiences with backed up sewage and lack of drinking water while in custody.

Access to water and good sanitation are frequently interrupted because of broken plumbing or contamination. Ankle deep sewage is not an isolated event. Blankets and coats in normal winter conditions are sorely lacking and insufficient.

These dismal conditions were the way of life during my almost two decades of incarceration, and they continue to be for the men and women on the inside now-to a devastating effect.

As media reports and personal accounts about the dire conditions in state prison and county jails during the storm continue to come to light, I suspect that prison and jail officials will try to convince the public that these are rare, unavoidable incidents.

They might say something trite, like we can’t control the weather, however, they do control existing conditions and emergency planning. Previous emergencies such as Hurricane Harvey and COVID should have taught them that pre-existing problems with busted plumbing, broken supply chains, hunger and thirst, should have been expected to worsen during a disaster. Advocates are calling for legislation “requiring the creation of an emergency management advisory board to prevent future catastrophes.”

I know that it can be hard to empathize with those who are or have been incarcerated because our culture dehumanizes us, as if we are diminished simply because of our mistakes. The truth is that we are as human as the neighbors you checked in on. We are as human as you and your family.

And now, because of the storm, the men and women in prison are not the only ones to know what it feels like to be cold, hungry and without water.

Jennifer Toon is a formerly incarcerated criminal justice advocate who was born and raised in East Texas. She attended Kilgore High School, and U.T. Tyler, and studied journalism at The University of Houston. She has 25 years of criminal justice involvement inside and outside the gates. Jennifer has written for the state prison newspaper, The Echo, for over ten years and as a freelance writer she has published work with The Guardian, The Texas Observer and The Marshall Project.

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.