Thanks to a mutual friend who helped put us in touch, I recently made a phone call to Alberta, Canada. It has been 12 years since Higinio Fernández-Sánchez has called Tyler home, but his roots here run deep. He remains deeply connected to his parents and siblings in Tyler, and to local mentors whose advocacy for immigrants has emerged, in part, because of Higinio’s story.

Another reason Tyler remains a touchstone for Higinio is because of a moment that changed his trajectory forever. He followed advice from a Tyler Junior College academic counselor that ultimately had him banned from the United States for 10 years, and lead him to a second and third life as a student, teacher, activist and researcher in Mexico and Canada.

I ended our phone call struck by the power of a legal formality to seal a person’s fate. Indignant, my mind reeled to visions from the story of the starving Jean Valjean who stole a loaf of bread and received a grueling sentence in Victor Hugo’s famous Les Miserables.

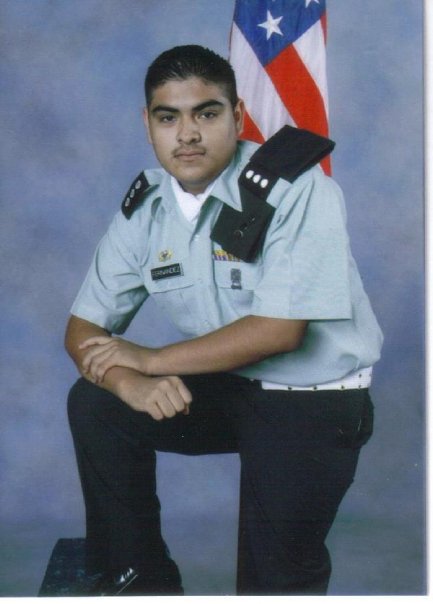

Higinio was without any such drama. He spoke calmly and confidently, describing the hardships and opportunities of the last 12 years. Long gone was his shock and disbelief, replaced by resolve. Higinio has faced the difficult task of meeting his fate and finding ways to work it in his favor. Here is his story in his own words, edited for clarity. All photos are courtesy of Higinio Fernández-Sánchez.

“My mom said I was a smart kid. I started to write and read at age three. I went to kindergarten in a small town called Agua Dulce which is in the county of Papantla, Veracruz, Mexico. My mother’s siblings lived in Tyler, hence why my parents chose to come here. I came to the U.S. in 1991 with my family when I was about five years old. I am the youngest of four siblings.

Tyler was my home throughout my school years. I attended T.J. Austin Elementary and Hogg Middle School, and I graduated from John Tyler High School in 2006. Then, I received an associates degree from Tyler Junior College.

I started taking college courses in my senior year in high school. I loved the idea that I could become a professional. At first, I wanted to be a lawyer, but later I became a Certified Nursing Assistant and had my clinical rotations at a nursing home in Whitehouse. After that experience, I knew I was going to be a nurse.

I had been working after school at a small Mexican grocery store since the age of 13, and when I finished high school, I worked at Burger King on Troup Highway. My parents and I paid for my two years of college at TJC without any financial assistance. My siblings weren’t too big on higher education, but they always encouraged me to do it.

As I explored my post-secondary education, the cheapest option for me was to start at TJC and then attempt to attend UT Tyler. In the fall of 2008, when graduation from TJC was approaching, I went to UT Tyler to speak to a counselor. I wanted to apply for the Bachelor’s Program in Nursing. In short, she believed I wasn’t suitable to attend UT Tyler and encouraged me to stick with TJC.

I believed her and went back to the nursing program at TJC. There, the counselor said that it wasn’t going to be possible unless I had a social security number. She advised that I go to Mexico and apply for a student visa at the U.S. Embassy. She said TJC would extend a letter of acceptance, which they did.

When I arrived in Mexico, which was basically a foreign country to me, the immigration officer denied the visa even with that letter. I received a 10-year ban from entering the States, because I had lived in Tyler for a long period without legal documentation. I was told that if I had left the States before turning 18, I wouldn’t have had this issue, but I was already 21 by the time I left Tyler.

Going back to Mexico was initially a happy moment, as I was going to have the chance to meet relatives that I had not yet met or didn’t remember meeting. After going to the embassy, though, I was devastated. I didn’t know what was going to happen. I thought to myself, ‘What I am supposed to do here? I don’t know anyone, I speak broken Spanish and I can’t read it or write it properly. What about my parents, friends?’ So many things went through my mind, it was basically going through a process of grief. At that time, it was definitely the worst thing that could have happened to me.

I lived with my grandmother for a few months until I moved to study nursing in a different city. I started my undergrad in 2009, only six months after arriving in Mexico, at Universidad Veracruzana. In 2010, the same university offered me a part time job as an English instructor. I taught English there for almost 10 years.

Living in Mexico for me was tough and could be a dangerous place to live. This is especially true if people know that you have lived in the U.S. or if you have family in the U.S. Being ‘not Mexican enough’ was always an issue. Sometimes, my ideas would not fit in with the typical, traditional patriarchy culture of Mexico. This was the case for at least the first year of my return. Thereafter, my language skills began to improve, and I started to make new friends who also helped with adjusting to life in Mexico.

Living in Mexico taught me many lessons. I was able to learn to speak, write and read Spanish properly. I learned how to appreciate the things that I had. I became an activist for human rights, especially women’s rights. It allowed me to complete two degrees with full scholarships and provided me with good jobs. I was also able to travel to Europe three times either as a student or as a faculty.

In 2012, I was able to travel to a nursing conference in Luxembourg, and I then fell in love with research. In 2014, I decided to pursue my Master in Nursing in Mexico and got a full scholarship from the National Council of Science and Technology. During that time, I had a research placement in Toronto with Dr. Souraya Sidani, based in Ryerson University, and she has been my mentor ever since. She is one of the reasons I ended up in Canada for my PhD studies.

Living in Canada is great except for the fact that my family isn’t here. I came to the PhD program with a full scholarship from the National Council of Science and Technology. The Canadian government also awarded me the most prestigious and most competitive scholarship for doctoral students. Here my work is highly valued, and it’s seen through a few awards I have received thus far.

While living in Tyler, I would teach English to friends and neighbors who didn’t speak the language. It was difficult to advocate for the migrant population, given that I was an undocumented immigrant myself.

In Mexico, I primarily advocated for women who had suffered some kind of violence — physical, sexual or psychological. I was part of a group that ensured women in our town received proper medical care in case of sexual assault, especially abortion rights in case of pregnancy due to rape. I also started to advocate for migrants who had been deported and had gone through the horrible deportation process from the U.S.

I have now moved from the typical activism work to an academic activism, meaning I will now engage in research with an activism purpose. My doctoral research will explore the experiences and health needs of left-behind women in Mexico who have a returning migrant partner. A difference between doing activism in the U.S. or Canada and in Mexico is that in Mexico, you place yourself at risk. It is well known that activists are followed and sometimes murdered. This is less likely in Canada or the U.S.

Dr. Karen Jones who leads Mustard Seed Ministries in Tyler started a non-profit called East Texas Immigrant Advocacy and Resource Center. After my experience of being stuck in Mexico, this organization began to help the immigrant community in East Texas. Through her leadership, she has been able to assist many immigrant families, including DACA recipients. Additionally, Paulina Pedroza, a well-known activist for the Hispanic community in Tyler, has expressed how my story has influenced her work. I truly appreciate the work these community leaders do, and I am thrilled to know that my story has served as an inspiration to help others.

I hope that regardless of their immigration status, all students are given the opportunity to pursue higher education. Our Hispanic communities have the potential to contribute positively to the larger community when we are given that chance. I hope that others can join people like Paulina and Karen to fight for immigrant rights, which are human rights.

If I one day return to Texas, I would love to join one of the faculties of nursing at UT Tyler It is a strange thing when people ask me about home — I don’t even know where home is. I do know that Tyler is and will always be in my heart. If I am given the chance to expand my professional career as a nurse researcher, I would conduct my research in the field of migration, health, and gender with a critical lens that has a political agenda. In short, I would continue to develop my academic activism.

If I could go back and speak to my young adult self heading into that counselor’s office, I would tell him: Listen, ask more questions, don’t be afraid to challenge the status quo. And remember that not everyone is going to wish you success.”

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.