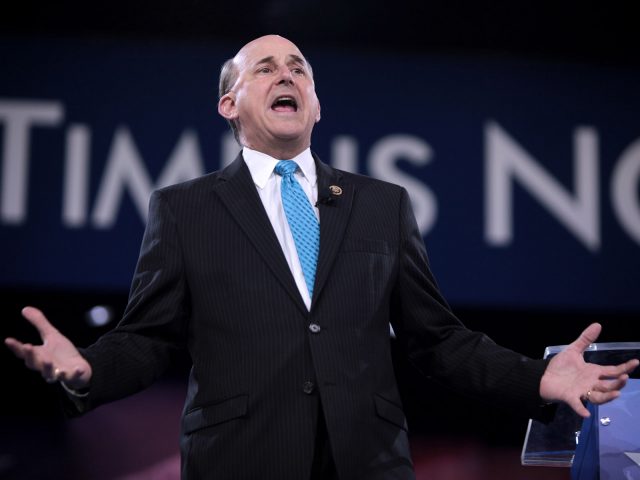

If you’re unfamiliar with the rhetorical stylings of Louie Gohmert, the Republican congressman who represents Tyler’s district in the U.S. House of Representatives, here’s a sampling.

Gohmert once suggested that Alaska needs a new oil pipeline because it would help caribous find love. He said repealing “don’t ask don’t tell” would encourage gay soldiers to sit around “getting massages all day.” And he said foreign terrorist organizations are sending pregnant women to have babies on American soil so that “twenty, thirty years down the road, they can be sent in to help destroy our way of life.”

Gohmert regularly draws national attention for making such pronouncements on TV and radio. According to our analysis of the Congressman’s Twitter feed, he’s made at least 98 media appearances so far this year — 53 of them on Fox.

Here’s something Gohmert does less of: legislate. According to a ranking by non-partisan Congress-tracking website GovTrack, in 2016, Gohmert was in the bottom half of all legislators based on the low numbers of bills he introduced or sponsored, and the likelihood of those bills passing out of committee. He also missed more votes than most of his peers.

Of the 105 bills the congressman has sponsored over the years, just eight have passed the House — including a resolution praising the US Men’s National Soccer Team. He has never sponsored a bill that became law. (Gohmert’s office did not respond to our request for comment on this story.)

Despite his lackluster record, Gohmert has consistently received at least twice as many votes as his nearest opponent since becoming a congressman in 2005 — when he even had an opponent, that is.

Since his first race for district judge in Tyler in 1992, Gohmert has won 17 consecutive elections (counting primaries). In nine of those, he ran unopposed. Whenever someone bothered to run against him, they got crushed. Shirley McKellar, his Democratic challenger in the past three Congressional elections, has never received more than 27 percent of the vote.

How does a politician with a weak legislative record, who once warned that giving China money to help protect endangered animals would result in “moo goo dog pan and moo goo cat pan,” maintain such a long winning streak? To understand Gohmert’s long-standing hold on District 1, Tyler’s district, you need to understand how he got his seat in the first place.

Redrawing the map

Back in 2003, Republican legislators redrew the boundaries of the Texas House in their favor. They did it through a highly controversial process known as “gerrymandering” that’s been employed at different times by Republicans and Democrats alike. In this case, hordes of Democratic voters in Texas were moved, or redistricted, into heavily red districts where their votes would be easily outnumbered.

Texas Monthly explains how it happened:

Following the lead of then-House majority leader Tom DeLay, an exterminator by trade, lawmakers in Austin had seized upon the historic election of a Republican Speaker in the Texas House as an opportunity to adopt a Democrat-zapping map and produce a Republican majority in Congress…He and his allies in the Texas House went to work on the congressional maps, targeting every single Democrat, regardless of voting record or the importance of committee assignment. Party was the only thing that mattered.

Tyler was moved out of District 4 and into District 1. It went from a district where 58 percent of voters had favored a Democrat in the previous election, to one where 62 percent of voters opted for the staunchly conservative Gohmert the next year. That’s the dramatic, transformative power of gerrymandering.

The 2003 reshuffling is among the most controversial examples of this practice; it’s been the subject of near-constant lawsuits since it was enacted. Earlier this year, a federal court ruled that three of the Texas districts had been gerrymandered to intentionally disadvantage minorities, violating the Voting Rights Act. (Tyler’s new district, District 1, wasn’t one of them.) Groups representing black and Hispanic Texans are now pushing for the entire map to be thrown out before the 2018 elections.

Of course, it’s entirely plausible that Gohmert would have had a long career in office even if the map hadn’t been redrawn. As the headline-grabbing face of far-right East Texas conservatism, he’s been bouyed by campaign donations from local businesses, waves of tea party fury, and the polarization of national politics. And once elected, it’s rare for a politician to be challenged by a member of their own party, no matter how few bills they’ve passed or how outrageous their antics. Love him or hate him, many in the region are convinced Gohmert can’t be beat.

But even in the most normal of political eras, the party in control of the White House tends to get dinged in midterm House and Senate elections. Gohmert is up for re-election in 2018. With the GOP in jaw-dropping levels of turmoil and President Trump’s ratings at historic lows, some are seizing this unusual moment to try to get under Gohmert’s skin.

Indivisible of Smith County, the local chapter of a national progressive movement formed after the election, has mounted a campaign to get Gohmert to hold in-person, public town halls. In April, signs reading “Missing: Our Congressman” and “Where’s Louie?” were posted in and around Smith County. Baskets of Easter eggs containing handwritten constituent questions were delivered to his office.

Earlier this year, Gohmert made national headlines when he refused Indivisible’s demands for town halls by invoking the Gabby Giffords shooting, saying a public forum would put his constituents’ lives in danger. (“Have some courage,” Giffords fired back. “Hold town halls.”)

And progressives aren’t the only ones expressing dissatisfaction. In March, John Coppedge, a retired general surgeon in Longview who calls Gohmert a “good friend,” took the congressman to task for blocking the first Republican health care bill. “I supported Congressman Gohmert from the first days of his first campaign for Congress,” Coppedge wrote on local sites and at The Hill, a national political news site. “I closed my medical practice and drove him all over East Texas to meet community leaders, meet with newspapers and hold campaign events. We agree on most issues.”

But, Coppedge continued, “governing is about more than making speeches, appearing on talk shows and being against everything. Congress will never pass a bill that Louie Gohmert thinks is a perfect bill — one that fulfills his entire wish list. So he kills Obamacare repeal and lets us keep paying the price for his purity. Louie, do you work for us?”

It remains to be seen whether these salvos and the continuing scandals engulfing Gohmert’s party will inspire a serious run for his seat, by a Democrat or just a more flexible Republican. Moreover, if a well-organized, media-savvy opponent does emerge, it’s hard to guess how Gohmert will react. He hasn’t had to run a real campaign in years. While we wait to see what happens in 2018, we can continue to rely on our congressman for entertainment, if not his legislative prowess.

Tasneem Raja contributed to this story.

The image at the top of this post is by Gage Skidmore. It has been reused under the Creative Commons BY-SA-2.0 license. It has been cropped.

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.