Jeff Williams and I met over FaceTime last week. His life as an engineer, project manager and president of Tyler Together Race Relations Forum have been informed by one factor: Williams is a Black man living in the United States. Our conversation included George Floyd’s death to raising his sons to his highest aspirations for his hometown, Tyler.

I’d like to hear about what the past week has been like for you. What have you attended, and what are you seeing in Tyler?

“This whole environment in which we live right now has been somewhat frustrating because, before I was president of the Tyler Together Race Relations, I was a Black man. I grew up as a young, Black man. I have sons and grandsons, so all of my legacy are people I’m concerned about. It’s tough sometimes to balance that between my responsibilities representing a very diverse organization and then my own experiences as an African American man.

“Due to health issues, I’ve not been out as much as I would typically. But I did get a chance to attend a rally and a prayer vigil. The rally was on the square with the elected officials. I ended up having conversations with a number of people. We attended the prayer vigil at Liberty Baptist. We have kept up with sharing, particularly on social media, all of the events that we know about.”

Walk me back to Memorial Day and when you first received news about George Floyd’s death and from there, how did things pick up?

“I had to spend a day or so just grieving. It’s tough. It’s not news. It’s just bad, and it just keeps repeating and repeating and repeating. From a personal standpoint, it was a little bit harder when they had the protest and the burning down of the Target.

“I’ve been in that Target. I moved to Tyler from Minnesota. And down the street from that Target, I used to get my hair cut. That kind of gave a little bit of a different perspective, and it took me a little while.

“I’m always trying to understand the responsibilities, and I’m a very pragmatic person. I want to deal with practical things and solutions, but yet I had to go through my own grief process.”

When you start turning from the grief to the practical, what comes to mind?

“We’re not in this for the moment. This is a commitment because this has to be a movement. Tyler Together has some initiatives — some of them I cannot announce because we don’t have formal agreement on those. We’re looking for not what happens in the next six days or next six weeks or even for the next six months. We’re focused on things that can have a long term continuity in making change.

“What we had to do is look at ways we could bring the entire Black community together. There’s a lot of very good organizations that do a lot of positive things within our community. However, we don’t have enough of us that come together and think strategically of ways we can have an impact, to speak as one, larger critical mass, so that those voices can then be heard. That’s what really makes a difference, when you start bringing and focusing on practical things as a large group.

“I think President Obama said something yesterday in his remarks: ‘You have to make people uncomfortable so that they’ll listen. Once you have them listening, then have something to say.’ Have something you want done. I always tell people, ‘It’s not just enough to say it, either. You have to champion it.’ Find out whatever it takes to move the obstacles, so they will help you champion your causes.”

When you talked about needing that strategic oversight for all the smaller groups in Tyler, do you see Tyler Together as taking on that role?

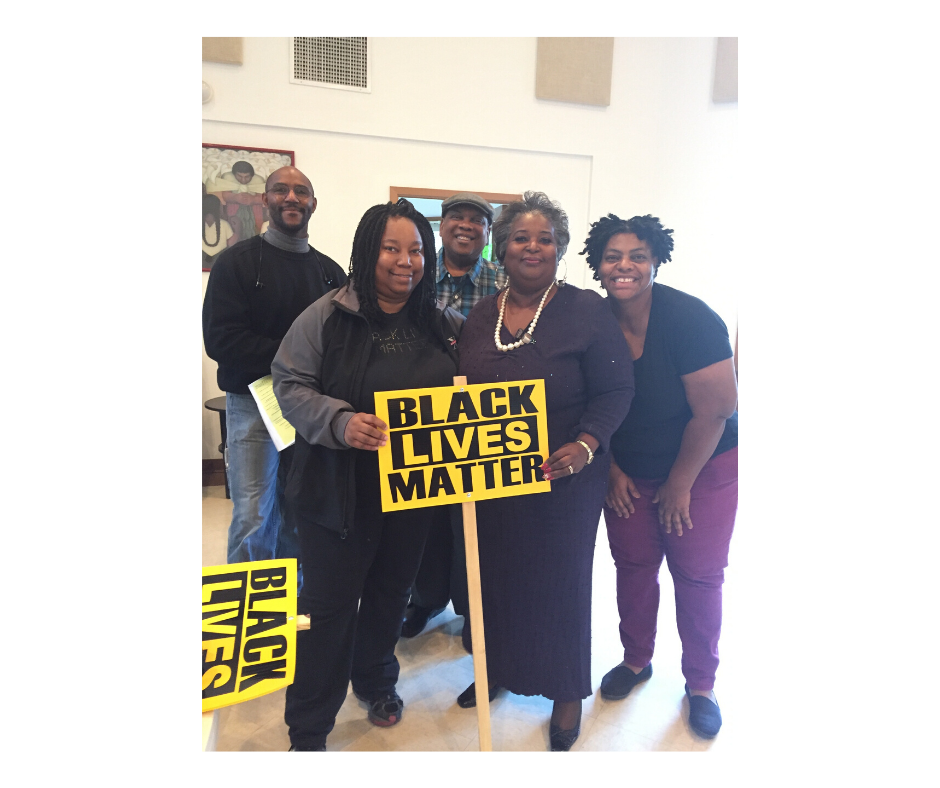

“Tyler Together develops relationships. Relationships matter, no matter what people want to say. We’ve been developing those relationships so that we can then be comfortable and talking, saying the difficult conversations. The thing about Tyler Together is we’re committed. We actually started in 1992. We’re not going anywhere. We love our community.

“Even though I’m an African American male who’s the current president, Tyler Together is a very diverse organization, and we welcome anybody. We have people from all different denominations, religions, ethnicities and all of those people, I trust, feel valued and appreciated.

“That’s the real gist of the problem. For George Floyd and for myself and other people, people don’t value and appreciate you. They think of you in a different light than they think of themselves or their neighbor, sister, brother. They don’t value you as much. They don’t value your life. That has a long history in America. What we have to do is get to a point that people see us and people respect us, and we love each other, not just in word but in deed.”

You mentioned that Tyler Together has been around since 1992. I’m curious about how local and national events, including police brutality against Black people and the Robert E. Lee high school name change movement have changed some of the conversations of Tyler Together.

“Tyler Together is not an activist organization. When I started in the presidency, I helped encourage everyone, saying, ‘We need to start doing forums.’ The mayor’s been to our forums, the police chief comes to one almost every year. It’s an annual thing because he has annual reports that he puts out. The fire chief has been to our forums, the sheriff.

“We try to talk about things that have relevancy to the community. We also have around 15 other organizations that we consider community partners. We have made some really simple yet strategic approaches.

“One, we show up. That may seem like a very simple thing, but we show up at places that people were not used to seeing other people that did not look like them.”

Can you give me some examples?

Well, like Leadership Tyler’s annual event and The State of the City annual event. I’ve been in banquets where the only two Black people there were me and my wife. You have to get out of your comfort zone. It’s very strategic for us.

“One of our white friends came to a Black sorority banquet. People were like, ‘Was she lost?’ My wife went right up to her and hugged her and said, ‘Here, I’ve got a place for you at our table.’ It goes both ways, right?

“When you show up, you then have an opportunity when people in your circle have a derogatory remark about an African American. You can say, ‘Well wait a minute, I know some people. I know how they are.’ When they talk about a Muslim, you can look at them and say, ‘All Muslims are not terrorists, because I have Muslim friends. Not just people who I know, but my friends.’

“Another reason we show up is to keep the conversation correct. When people bring up the conversation, you can stop it. Keep the conversation from a ‘they’ conversation. There is no ‘they.’ We are ‘they.’ Let’s be real: There are people who have not been in parts of this city who may not even be concerned about parts of this city. This is a ‘we’ thing because what affects me, affects them. It may seem that those two simple things — showing up and keeping it a ‘we’ conversation — are simple and small. But they are very impactful.”

When you were talking about the easy conversations and the hard ones, can you give me some examples.

“Some of those are private, you know. Let me give you a for instance. You brought up the Robert E. Lee name change, right? We had some commissioners, elected officials, who had some things to say about that.

“We met over coffee, and we talked about that. I had to work through an intermediary who had become a friend of mine. We developed that relationship over six months. That intermediary became comfortable enough to make the introduction to someone else.

“So that took six months or more before I could get the meeting through an intermediary. But we made it, and now we are associates, and we can talk about some of the more difficult conversations.”

I’m trying to imagine you sitting down and having coffee. At what point does that conversation get difficult? Is there certain language or ideas that are the trigger points?

“Yeah, well, there’s already public comments out there. Just having to bring those up to say, ‘What did you mean by that? Did you understand your comments and what their effect was in the community? Is that how you want to be viewed?’ That’s pretty tough to do sometimes.

“We’ve also had to have some conversations with people at dinner tables, at banquets. People would bring up, ‘I don’t like the phrase Black lives matter.’ And I’ve said, ‘Well here’s the reason. I hear what you’re saying, that all lives matter. But my life doesn’t matter as much.’

“They may not understand or accept it, but having a conversation is important. There are still people in our community who will not say, ‘Black lives matter.’ They will not do it. They have that comeback. They don’t understand how offensive that is to a Black American. If it matters the same, we wouldn’t keep having these same incidents [of police brutality] over and over and over again.

“It comes back to our country. When they were looking at the electoral college and the voting, they only counted African Americans as three-fifths of a person. So, we have a history on that.

“I encourage people to go back and read the 13th Amendment that came about to abolish slavery. It has on the first sentence a big exception that talks about, ‘Unless you’ve been lawfully convicted of a crime.‘ That’s why our prison population is in such disproportionate ratios. There are so many more Black people in prison. People have not understood what it takes to make sure we change laws to affect us as Black Americans.”

Knowing that you had some life experience in other places, I would love to hear how East Texas struck you with its particular challenges. When you talk about the history of our area, where do you see remnants of old thinking still affecting us?

“I came to Tyler in 2006 for a job. My background is engineering. Frankly, I had never been to Tyler until I interviewed for that job. One of the things I looked at and considered was the name of the Robert E. Lee High School. I thought to myself, ‘Wow.’

“I talked to my son because they played football. He said, ‘Dad, they don’t even call it Robert E. Lee, they call it Tyler Lee.’ I said, ‘Wow, son, okay.’ Obviously, I still came here, but the point being that I even had to think about it.

“The places I lived were much larger cities the majority of my adult life. When I moved to Tyler, I lived on the south side of town. Economically, I could afford to live wherever I wanted to, just about. But I went to church on the north side of town.

“When I came here, the city council had seven members, and six of those members were real estate developers. Tyler is very much tied into real estate developers and those are also tied into our Chamber of Commerce.

“I went to the Chamber of Commerce when I came to Tyler. I walked through the door and said, ‘I want to find out more information about the Chamber of Commerce,’ and the lady said, ‘Are you sure you’re at the right place?’ I said, ‘Well, I think so. This is the Chamber of Commerce.’

“I had not been in a city that had a Black Chamber of Commerce before. That was different to me. I ended up taking time to say, ‘Look, who can I talk to, what information?’ And so, she finally got on the phone and had somebody I could talk to about joining the Chamber of Commerce.

“That was a little shocking to me. When I joined the Chamber of Commerce in the Humble, Texas, area, they were very excited and open. Probably 80% of my business came from chamber members. I was expecting the same type of thing when I came to Tyler, and that was not the case.”

When you were at the rally and the prayer vigil, can you recount to me what the mood was like?

“I’ve been to so many vigils. I try not to be cynical. I’ve had so many things that people come for, and they do things in the moment, but I can’t find them six months from then. It was good, the vigil that night had a lot of positive people. They put an emphasis on voting. If we are going to change things, we have to vote in elected officials who will help change the laws.

“[The rally and the vigil were] full of people, it wasn’t a sparse crowd. We have a lot of people who are actively engaged. The thing is staying engaged and coming back with practical solutions.

“The prayer vigils are there to get the grief out. We’re hurting, our country’s hurting. The protests are there to get attention to say, ‘We need to change.’ After we have the attention, we need to be able to say, ‘Here’s what I want done. I need this done.’

“Candidate forums and having candidates on record on what they say, asking them those direct questions is very important. And then let’s move forward and hold them accountable. And if they’re not doing it, let’s get them voted out and find somebody who does. That’s the activist in me.”

When you think about the life you’ve lived as a Black man in America and also the long term relationship you’ve had with Tyler Together, what do you wish people knew?

“This is not new. The only difference is being on film. What concerns me is how many George Floyds were there on that same day? I’ve been stopped — not as much now because of my age — and maybe because I’m wiser, too.

“Believe it or not, there are still places I don’t want to be seen after a certain time, and I’m not out at night. But I was stopped when I was younger.

“I was stopped one time when I was driving my mom’s car because my license plate was too dirty. I had to get out to clean my license plate. I was like 20 years old.

“When I lived in Houston, I was followed around. We were the only Black family in that subdivision. I would go on a different route so I could learn the neighborhood, but also because I could see they were following me until they got used to me being there, and that took about three weeks.

“My sons have both been stopped. One of my sons is in the entertainment business, so he comes home from night clubs real late. He knows the routine. Here’s something people don’t even have to think about.

“My son bought a new car. Instead of buying one of the slicker ones, he bought a Jeep. He said, ‘Dad, I bought a Jeep so I won’t get stopped so much.’ Most people don’t have to think about that. But my son is 35 years old and lives in Atlanta and got tired of being stopped.

“We have to consider race. We can’t say, ‘Well, why talk about race? Why bring it up?’ Well, it’s part of my everyday life. I have to consider where I am, who I am, how I am being perceived, how others perceive me.

“My voice is very deep, but I do change my voice at times. I’m a big, Black man. I’m not a small one. I can come across as intimidating. I have to make sure I keep my distance from people. I’ve learned these reactions throughout the years. We have to adjust that in whatever environment we’re in, whether our jobs or just in the general public. It’s a different world, but it’s the world in which we live.”

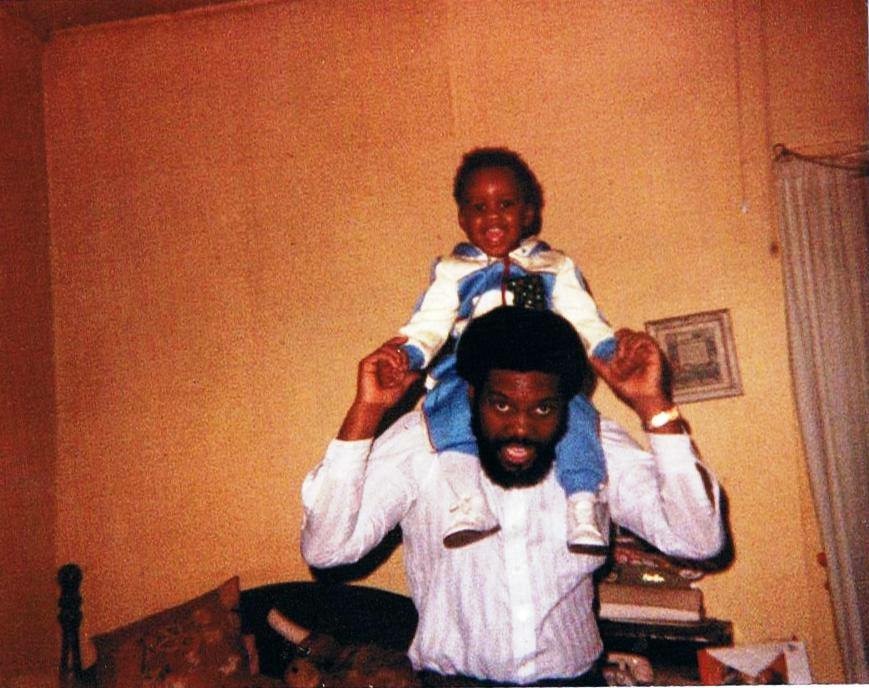

How did you prepare and train your sons to navigate the world they live in?

“Particularly, my older son, we had conversations about not to be disrespectful, not to say anything. Those conversations started around 10 [years old]. My son’s a very big guy, too. I had a sit-down with him, but these are multiple sessions that we had. As he grew, different things would happen.

“He got picked up once. He was 16. He was at a store, and they accused him. An off-duty police officer said he stole a magazine. He was on his way to his driver’s lessons to get his license.

“He didn’t say anything, he went on in. He called me, and I bailed him out. I said, ‘What happened?’ He said, ‘Dad, I got money in my pocket, like $20. Why would I need to steal a $2.50 magazine?’ I said, ‘Yeah, but you made it home.’ So these discussions are not a one-time thing.

“Now, he’s old enough. He owns a security company. He has a number of police officers who work for him, so he knows a lot more police officers. He doesn’t get stopped as much. Understand what I said: not as much. He still gets stopped. It’s something we live with.”

Have your sons had an experience you didn’t have yourself, a sign of times changing?

“The first time my son had a police officer pull a gun on him, he was 13. That was at a basketball court. I didn’t have it happen that early. I didn’t have a lot of interaction with the police when I was growing up.

“I happened to have had very good grades, to be very well known and had a lot of good allies. The Jewish community, the rabbi — I worked for him after school and on weekends. That community, believe it or not, provided me with opportunities that I would not have had available to me because of my relationship with them.”

Did you have a parent or mentor who gave you a similar sit-down and talk to you explicitly about what was happening?

“I had both. I had people who made a difference in my life. They called it the CETA (Comprehensive Employment and Training Act) Program for low income students. I worked for the city. I was used to working really hard. I was cutting grass and half a mile down from where the other boys were.

“The supervisor was a school teacher from a smaller town. He took me under his wing. He would say, ‘Just ride with me the rest of the day because you already did more work that everybody else.’ He gave me a lot of life lessons. He taught me a lot of things, particularly about how to deal with people. He said, ‘What I want you to do is pass [this] along to whatever boy you have. Help them understand how to live within this world.’

“I will be honest. In corporate America, most positions I held, I was the first Black in those positions. When I was an engineer, before I moved into management, there were people who would not respond when I would come in and ask a question.

“They were like, ‘Who are you, and where did you come from?’ They weren’t used to having Black engineers. I had difficulties with some college professors, but I learned how to navigate that, how to find my allies. When I moved into management, I became a mentor to minorities — women, people of color — whether they worked for me or not.”

Talk to me about best case scenarios. If the protests and vigils do gain some traction into a movement, a critical mass, what would that look like, and what do you imagine that group would be working toward?

“This is the year of the census. We need to be paying attention to the census and how districts are being drawn. The districts and the percentage of people on the various City Council and School Board — they should represent the demographics of the community. They currently don’t do that.

“The community itself in Tyler, Texas, is a majority-minority community. If you come, and you do not have the potential for a majority of representatives from minority communities, then there is a problem as to how the districts have been redrawn. That would be a telltale sign to me.

“Also, I think we need to elect the right representatives, both the state representative and senator, that will look at changing some of the laws. Our peace officers have to be able to enforce the law. There are some gray areas, but some areas have been written that are specifically set up to hurt people of color.

“Electing the right people who will make a commitment to people of color and their communities is very important. As we look at our elected officials on the local level — the sheriff, county commissioners, judges — the same thing has to happen.

“The county commissioners, we have four. If we look at the demographics of the city, we should be able to see that we have a potential to elect at least two people of color. You can’t represent people who you don’t know.

“Also, looking to the future of our local, elected judges. Right now, the perception is that sentencing is not equal. It’s not representative. If you are a person of color, there’s talk of the same type of offense having a totally different sentencing. We need to have those dialogues.

“Our current police chief and current fire chief both want to see a more diverse workforce. When Chief Cobble was hired by the City of Tyler, he was the only Black person in the whole fire department. Our fire department was 100% Caucasian. He has done a good job of trying to improve on that, bringing in more minorities.”

Is there anything else important to you to say that was not addressed yet? Anything you would like people to know, understand?

“I have to give credit to our current mayor [Martin Heines]. One thing we continue to say is that we can talk. He will listen and wants to listen, recognizing that he is the mayor for the entire city, not just for part of the city.

“I look forward to the next administration, to being able to continue those dialogues. The people we elect work for us. We have to let them know what our expectations are and hold them accountable.”

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.