In the 1994 film, “The Shawshank Redemption,” actor Morgan Freeman portrays a prison inmate nicknamed “Red” who addresses a parole board after serving 40 years of a life sentence.

He’s asked if he has been rehabilitated.

Red characterizes the word as a “made-up word, a politician’s word” and poses the real question: “Am I sorry for what I did?”

His answer goes to the heart of the matter.

“There’s not a day goes by I don’t feel regret. Not because I’m in here, or because you think I should,” Red responds. “I look back on the way I was then — a young, stupid kid who committed that terrible crime. I wanna talk to him. I wanna try to talk some sense to him … tell him the way things are. But I can’t. That kid’s long gone and this old man is all that’s left. I gotta live with that.”

Red wins his release but realizes as a free man he still feels alienated from society and considers re-offending so he can return to familiar surroundings.

The fictional scenario reflects today’s real-world issues as the criminal justice system rethinks life sentences for juvenile offenders and whether it’s possible to re-integrate them as productive members of society.

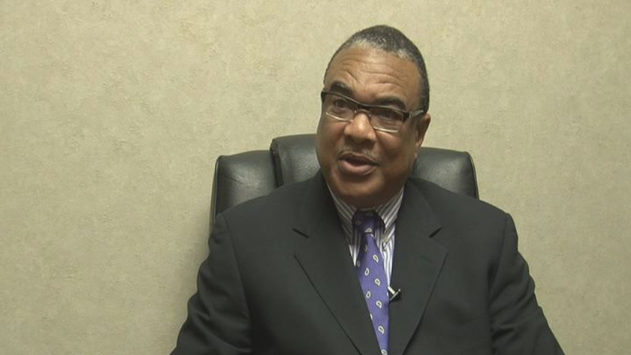

Not everyone is convinced sentencing needs to be under the public microscope, however. For Smith County District Attorney Jacob Putman, rehabilitation is only a part of the judicial system equation.

He’s “resistant” to changing sentences retroactively for incarcerated adult offenders, even those who committed their crimes when they were younger than 18.

“I think the judge and jury … try to make an accurate punishment assessment of what the case is worth at the time, having heard the facts and knowing what the parole law was at the time,” he said.

Although a focus on rehabilitation is sometimes warranted, Putman said it is not the only reason for sentencing offenders.

“I think we also sentence people because they’ve committed a crime, that punishment is for retribution,” he explained. “It’s the punishment you deserve for the crime committed.”

Still, Putman says he recognizes life sentences given juvenile offenders is a “complicated question.”

“I’m always open to see how we can improve our criminal justice system and improve our sentencing system,” he said. “ (but)… my initial instinct is to hesitate to end sentences that were done by people in a meaningful, case-specific way.”

Tyler attorney Clifton Roberson has faced the punishment v. rehabilitation issue from both sides. As a former Smith County assistant district attorney, he prosecuted dozens of cases involving young offenders. Since opening a private practice in 1992, Roberson has represented dozens more.

Some offenders embrace the opportunity to rehabilitate themselves while incarcerated and live productive lives after their release while others reoffend soon after they are released, he said.

“I believe rehabilitation is possible,” he said, “but that’s going to be left up to the individual.”

Reform proponents, however, contend life sentences for juvenile offenders ignore the potential for rehabilitation by removing the main incentive for behavioral change. That incentive, says Alycia Castillo, a director at the Texas Center for Justice and Equity, is hope.

Harbinger of change

Recent court decisions just may be the catalyst for reform across the nation proponents have been waiting for. A succession of U.S. Supreme Court rulings put a damper on harsh penalties for some juvenile offenders.

In a landmark 2005 decision, justices ruled 5-4 to bar executing a person convicted of capital murder who was under the age of 18 at the time of the offense.

A death sentence under that circumstance constituted cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Constitution’s Eight Amendment, according to the majority opinion in Roper v Simmons.

“When a juvenile offender commits a heinous crime, the State can exact forfeiture of some of the most basic liberties, but the State cannot extinguish his life and his potential to attain a mature understanding of his own humanity,” according to the opinion authored by Justice Anthony Kennedy.

Subsequent Supreme Court decisions involving juvenile offenders: Graham v Florida in 2010; Miller v Alabama in 2012; and Montgomery v Louisiana in 2016; respectively, barred life without parole sentences in non-homicide cases and mandatory life sentences without parole as applied retroactively.

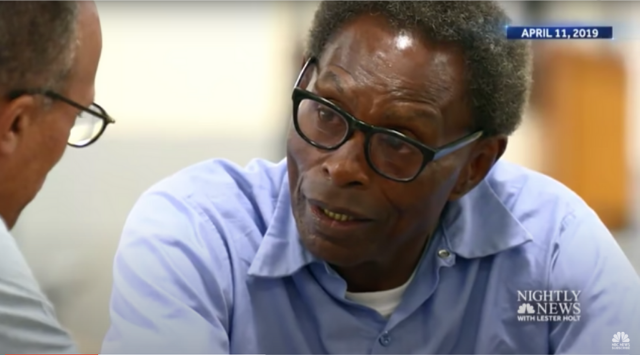

In November, Henry Montgomery — the plaintiff in the latter case — was freed from the Louisiana prison after serving nearly 58 years of a life sentence. Montgomery, now 75, was only 17 when he was convicted of killing a sheriff’s deputy.

In a previous interview, NBC Nightly News anchor Lester Holt asked Montgomery, “Do you remember what it was like being 17?”

“Young, wild and stupid,” Montgomery replied.

A national survey conducted by The Sentencing Project in Washington D.C. found that 1,465 offenders are serving juvenile life without parole — known as JLWOP — at the start of 2020. That count represents a 38% drop since 2016 and a 44% drop since the peak in 2012. The numbers continue to decline as more states eliminate JLWOP, according to the survey.

In 2013, Texas legislators banned the death penalty for offenders who were younger than 18, leaving a life sentence as the only option. Still, an offender under those circumstances must serve at least 40 years before becoming eligible for parole.

A life sentence for other serious offenses means serving at least 30 years before parole can be considered. Being granted parole, however, is not guaranteed. The decision may hinge on the offender’s conduct and rehabilitation efforts during his/her incarceration.

The second question

In the Roper opinion, Kennedy noted research on adolescent development shows a child’s brain — not just their bodies — are not yet fully developed even at the age of 18. As a result, they do not have adult levels of judgment or the ability to consider the risks or the consequences of their behavior, he said.

Teens also are more susceptible to peer pressure, generally lack impulse control and mature and markedly different rates, studies show. The level of maturity, therefore, cannot be on a “bright line” or set age standard like for voting, military service or drinking.

That brings up more important questions about the juvenile justice system involving JLWOL: Can offenders imprisoned as juveniles become productive members of society even after decades behind bars? Or, have they become so “institutionalized” as Red discusses in “The Shawshank Redemption” — that success outside incarceration is unlikely?

“These are questions that keep us up at night,” Castillo said. “How do we ensure accountability without creating harm and violence the prison industry creates?”

Studies show most adolescents don’t fully mature until their mid 20s, however, they have the greater capacity to reform or are capable of change. The justice center supports proposed legislation — known as the Second Look Bill — that would allow case reviews after a juvenile offender serves at least 20 years of their sentence.

“Providing that review, that hope of something to look forward to … so they can meaningfully engage in reform,” Castillo said. “No one’s asking … to just let them go free. We are looking for a meaningful review.”

Rehabilitation not only involves the offender taking responsibility but utilizing programs to improve themselves and prepare to be productive members of society, Castillo said, noting that many juvenile “lifers” have earned multiple educational degrees and participated in religious offerings.

Although post-secondary educational programs — both vocational and academic — are available in Texas prisons, Castillo contends there is an “abysmal, dark gap” in opportunities for young offenders who need psychological counseling, life-skills training and other educational opportunities.

Young offenders who are tried and convicted as adults, however, face incarceration in adult prisons and generally are treated like adults without the opportunity to participate in specific programs offered in the juvenile justice system.

Without assistance, offenders become susceptible to repeat the pattern of behavior that led to their incarceration. “We can’t simply give them $50 and a bus ticket and tell them to have a nice day,” Castillo said.

Efforts for change

Texas legislators approved a bipartisan bill known as the “Second Look Law” earlier this year but Gov. Greg Abbott vetoed it, citing concerns over possible legal conflicts with current jury instructions.

A revised bill is expected to be proposed during the next legislative session in 2023.

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.