Last month’s violent white supremacist protests in Charlottesville, Virginia reawakened a 50-year-old debate over Tyler’s Robert E. Lee High School. A recent school board meeting attended by nearly 300 people has demonstrated that Tylerites need better access to local history on this matter.

Most people who attended the August meeting might not know Tyler has been here before. In 1971, black Robert E. Lee students and parents repeatedly asked the Tyler Independent School District to rename the school. During a momentous school board meeting attended by nearly 400, a parent told the board that “black students at Lee feel the Civil War is fought over and over again each year between September and May.” Ultimately, the board kept the name. Now, 50 years later, the city of Tyler is grappling with the same question.

If we wish to settle the debate this time around, Tylerites — from school board members to current students, passionate alums to recent transplants — will need to understand how we got here. To that end, The Tyler Loop, in collaboration with former veteran Dallas Morning News reporter and longtime Tyler resident Lee Hancock, has taken a deep dive into Tyler’s history of race and education. We have compiled a timeline from 130 years of local news reports, yearbooks, school board minutes, court filings and regional histories, with original sources for each timeline entry. You can see those citations here.

We begin our timeline not in 1958, when Lee first opened as an all-white school, but further back, when Tyler’s first segregated schools were founded. We explain how anger over desegregation in other Texas cities and across the South affected the decisions of white leaders in Tyler. We include information about other race-related court cases fought here in Tyler, both because those fights impacted Tyler and to provide context about our city’s role in shaping the statewide and even national fight over desegregation.

And we show that none of these decisions was made in a vacuum, or in a casual fashion. School names, mascots, colors: these symbols are heavy with meaning, and they were intended to send a message. We know, because the archives preserve the words of those who selected and cherished them.

We want to hear from you: what relevant history have we missed? What additional facts or context can you share? Drop us a line: [email protected]

Chapter One: The birth of Tyler’s segregated schools, 1888 to 1950

Chapter Two: Texas’s fight against desegregation finds a home in Tyler, 1950s

Chapter Three: How Robert E. Lee High got its name and Rebel flag, 1957 through ’60s

Chapter Four: Court-ordered school desegregation hits Tyler, 1970s

Chapter Five: Lasting scars and unfinished fights, early ’90s to today

Chapter One: The birth of Tyler’s segregated schools

Late 1800’s to 1950

Race has been a charged issue in Tyler’s public education since the first schools opened here. Like their counterparts across the South, white Tyler leaders enforced segregation and funneled more resources to white schools. Tyler’s black community, denied meaningful say in local decisions, pushed for decent black schools. Starting in the 1920s, blacks rallied around a flagship high school of their own, named for a pioneering black educator. Go to next chapter, or read more of this history below. See original sources for all entries here.

1888

The first class graduates from all-white Tyler High School.

After a committee of black leaders asks for “a suitable school house” for black students, the city opens West End School for first through tenth grades in a four-room building on Herndon Avenue.

1923

West End School burns down, and a new school for black students is built on Border Street. It’s named Emmett J. Scott Junior High, and its mascot is the Bulldog. Emmett J. Scott was a Houston native, an administrator at Tuskegee Institute under Booker T. Washington, and a special assistant to the U.S. Secretary of War in World War I.

1931

A city development plan for Tyler recommends uprooting black neighborhoods near downtown for white development and strategically placing all “colored schools” and parks to keep black families in isolated areas of northwest, southwest and central Tyler. That will achieve white leaders’ goal of citywide segregation without risking claims about unconstitutional restrictions, a Dallas consulting firm writes, because “it simply will not be convenient for a negro family to live in any other section of the city.”

1939

A black delegation asks the school board for money to build a small shed “with hot water and cooking facilities” at Emmett Scott High School, so Scott’s PTA can make hot lunches for students. The board refuses the black community’s request. Though “the need was great” at the black school, and though the district already provided free lunches to needy white students, board members said they couldn’t afford the shed because they “already had an outstanding obligation to build an auditorium for the white school.”

1945

The updated city plan recommends removing Emmett Scott High School from Border Street and building a new school and park several blocks west to protect Tyler’s “present dividing line between whites and negroes.” Both recommendations are carried out.

1946

The school board discusses a $225,000 stadium for Tyler’s white high schools and junior college. The district can avoid the expense of a cheap field for black schools if they’re allowed to use the new stadium, too, an official says. This will work, he tells the board, if the new stadium is “erected away from the center of the population” of white Tyler.

1950

In September, the new Emmett Scott Senior High opens on Lincoln Street between North Confederate Avenue and North Englewood. Over the next 20 years, 12,000 black students will pass through its halls.

Chapter Two: Tyler becomes a segregation battlefield

1950s

Tyler makes national news as Texas officials launch a court fight here to counterattack legal assaults on Southern segregation. The state lawsuit comes two years after the N.A.A.C.P.’s historic win in Brown v. Board of Education, amid a wave of integration lawsuits in Texas and across the South. The Tyler court ultimately bans the N.A.A.C.P. from the state of Texas. That ruling will come just before Tyler school officials decide to name their new white high school after Robert E. Lee. Across the South in the ‘50s and ‘60s, new monuments are erected and new buildings are named to honor Confederate generals and history. The trend is widely seen — and even openly declared by some Southern leaders — as white backlash against the civil rights movement. Go to next chapter or read more about this history below, and see original sources for all entries here.

1954

The U.S. Supreme Court rules that segregated schools are unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education. It is a historic win for the N.A.A.C.P. and its chief lawyer, future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. In Tyler, black community leaders had enlisted state N.A.A.C.P. lawyers in an groundbreaking — though ultimately unsuccessful — earlier civil rights case, a federal lawsuit asking that black families be allowed to use Tyler State Park. Newspapers in Tyler follow legal battles and vows of white resistance across the South, running these stories as front-page news.

1955

The all-white Tyler school board says its integration policy will be the “same as last year,” meaning that total segregation will continue in Tyler schools.

1956

A federal judge in North Texas issues the state’s first desegregation order in a lawsuit brought by an NAACP-affiliated lawyer. White mobs repeatedly gather to block black students from entering a school in the North Texas town of Mansfield. Texas Gov. Allen Shivers sends Texas Rangers to back the school district’s defiance of the federal desegregation order. The crisis makes front-page headlines in Tyler.

On September 21, the Texas Attorney General files suit in Smith County District Court demanding closure of N.A.A.C.P. offices and chapters statewide. He alleges N.A.A.C.P. officials “exceeded the bounds of propriety and law” by recruiting clients for desegregation lawsuits, engaging in political activity and seeking to integrate Texas public schools. State officials choose politically friendly, staunchly pro-segregation Tyler as a favorable venue.The same day they file their suit, the Tyler state judge issues an emergency order: the N.A.A.C.P. must cease all activities in Texas. N.A.A.C.P. officials say the governor and attorney general are pandering to segregationists and denying black Texans their constitutional rights.

On September 27, the eve of what Tyler newspapers term a “life or death” hearing for the N.A.A.C.P., the Texas governor’s segregation commission calls for new laws mandating school segregation and prosecution of blacks who try to enroll in white schools. That makes front-page news in Tyler.

On September 28, hearings begin in Tyler in Texas v. N.A.A.C.P. The association’s offices across Texas and the homes of local black leaders are searched at gunpoint by state authorities, who seize membership lists and files to bolster their legal attack. Thurgood Marshall tells reporters that the Tyler case is the civil rights organization’s “most critical battle yet.”

In October editions of the Tyler Star, a local weekly tabloid, a black columnist writes that the state’s lawsuit amounts to “mob rule.” Describing the scene at the Tyler courthouse, he tells of “some 400 ‘potbellied’ people from Houston going in and out of our buildings passing out Confederate flags, not knowing it has been 90 years since the Civil War.”

On Oct 23, a Tyler state district judge extends his initial order, ordering the N.A.A.C.P. to cease operations in Texas.

1957

In April, the Tyler school board approves a $213,000 addition at Emmett Scott Senior High and a new $2.2 million white high school in South Tyler.

After more hearings and legal defeats for the N.A.A.C.P. in Tyler state court, N.A.A.C.P. chief counsel Thurgood Marshall negotiates a compromise with the new Texas Attorney general. The organization agrees to limit itself to educational and charitable work in Texas.

In May, N.A.A.C.P. Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins writes a confidential memo warning his national board that the Tyler court’s ruling is “so serious and has so many implications and ramifications… The problem now is what shall we do in light of the order. This goes well beyond the Texas situation and brings up the question of our whole method of operation in hostile Southern states, now and in the future.”

Though the organization will continue in Texas, its momentum will slow significantly both statewide and in places like Tyler, where adverse effects of the court fight reverberate for years. In coming months, some in the black community will see the school board’s decision to name the new white high school after Confederate General Robert E. Lee as a further rebuke of civil rights activism by groups like the N.A.A.C.P. and as a signal that Tyler whites have no intention of integrating the city’s schools.

Chapter Three: What’s in a name?

Late 1950s through ’60s

Tyler school officials name the city’s new high school Robert E. Lee High. For the next twelve years, the school’s white student body will be deeply immersed in Old South mythology as local leaders resist federal government demands to speed up desegregation. Go to next chapter or read on below, and see original sources for all entries here.

Late 1957

In October, the Tyler school board discusses naming Tyler’s new white high school South Tyler High and the existing white school Central High.

On Nov. 11, citing “extremely strong opposition” to the names South Tyler High and Central Tyler High, the school board leans toward naming the new white high school after Robert E. Lee or Benjamin Franklin. A decision is postponed for student input.

On Dec. 11, a Tyler Courier Times editorial urges the Tyler School Board to name the new white high school after the Alamo.

On Dec. 12, the Tyler school board considers 50 names proposed by white students for the new school. After several board votes, members agree to name it Robert E. Lee High School and the old high school John Tyler High School.

1958

An assistant principal for the soon-to-open Robert E. Lee High tells the school board that there isn’t yet a clear winner for school colors and a mascot from the new school’s prospective students. In student voting, orange and white beat red and white by just a dozen votes and black and white by a large margin. As for the mascot, the Rebel got 170 mascot votes, Travelers 105 votes, and Lancers 70 votes. Left unsaid in the summary of the board’s discussion is the likely dilemma posed by the students’ top color choices: what would local Texas A&M and Baylor grads say about orange and white — University of Texas colors? The board tells the high school’s principal to hold a runoff vote for colors as well as for a mascot.

1959

With the start of the new 1959-60 school year, TISD opens a new addition at all-black Emmett Scott High School and the new campus for all-white Robert E. Lee High School. Tyler’s Lee is one of several Texas high schools named for the Confederate general in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, amid resistance to integration across the South. (In Midland and San Antonio, high schools named for Robert E. Lee around the same time have also had recent name-change campaigns.)

1960

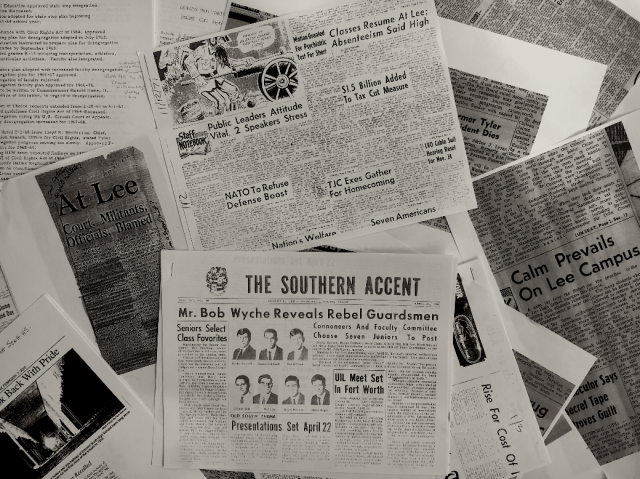

Robert E. Lee history teacher Bob Wyche forms the Rebel Guard, a select cadre of seniors who fire a cannon named Ole Spirit at athletic events. Wyche, a Confederate history buff whose American history classes focused heavily on the Civil War, will regularly take the Rebel Guard to Civil War reenactments, including ceremonies at Vicksburg for the 1961 Civil War Centennial. (After integration and a change in school symbols in 1972, the Guard will be renamed the Cannoneers. Its members will include boys from prominent Tyler families, including future mayor and state Sen. Kevin Eltife and future Tyler Morning Telegraph publisher Nelson Clyde. The group will disband in 1986, after the state’s interscholastic governing body bans noisemakers at athletic events.)

A 20-foot-by-30-foot Confederate flag is given to Robert E. Lee High School by Mrs. Julius Bergfeld, whose family is the namesake for Tyler’s historic Azalea District park. The banner requires a team of 20 boys, dubbed “the Lee Gentlemen, to carry it. (Mrs. Bergfeld’s grandson Andy Bergfeld is a current Tyler school board member.)

1963

Lee’s Rebel Guard gets new uniforms, replicas of those worn by a North Carolina Confederate artillery unit under General Lee’s command. Says one Rebel Guardsman, “We are very proud of our uniforms because of the traditions they represent.”

In June, TISD officials announce a “stair-step plan” for desegregation, starting with kindergarten and first grade. The plan calls for moving up each year’s integrated group of kindergarteners and first graders until every grade is desegregated.

1964

The U.S. Civil Rights Act is signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson, banning racial discrimination in all public accommodations. The act mandates termination of funding for segregated school systems and authorizes the Department of Justice to bring federal lawsuits to enforce integration of public schools. The federal Department of Health, Education and Welfare is tasked with developing and enforcing desegregation plans for school districts across the country.

TISD begins allowing students to voluntarily transfer between local schools regardless of race, as part of its “freedom of choice” desegregation plan.

1965

An editorial in Lee’s student newspaper, the Southern Accent, explains the Rebel Flag’s meaning for Lee students: “Without this flag, multiplied many times over, waving on car antennas and in the stands at the game, would ‘Dixie’ mean as much or the cannon sound as spirited? …[P]ride and symbolism of a school body completely supporting that team can be seen through that flag. Rebels, don’t bring that symbol down any lower than you would want your school and ideals to go. The bruises can’t be seen but the shredded flags can.”

1966

In a tradition reminiscent of plantation-era debutantes, Lee’s Rebelettes drill team is “presented” to the school in a ceremony the Southern Accent describes as decorated with “magnolia and wisteria blossoms, roses and a wishing well…[to] help create an atmosphere of the ‘Old South.’”

In July and August, shortly after federal officials warn TISD that its plan for integrating faculty is insufficient and its desegregation of its schools is moving too slowly, the school board approves a ten-year plan for fully integrating black and white faculty in Tyler schools.

In September, an editorial in Lee’s student newspaper urges students to live by the school’s founding principles: Lee students should be as hospitable as Southern gentry, as honest as Confederate gentlemen, and as hardworking as those whose “back-breaking work” wrested “such a magnificent way of life.” Lee students should foster pride in the Old South’s “way of life and all the noble ideas for which it stood. Pride wove together these men of courage and bravery and produced one of the most advanced civilizations known to mankind.”

In October, a victory over crosstown rival John Tyler High is celebrated with the declaration “The South rose again!” in the Southern Accent: “Spirited Confederate fans went into momentary ecstasy as the long dormant ‘Ole Spirit’ boomed and a raft of balloons floated skyward.”

1968

The Federal Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) again warns the Tyler School District that its desegregation efforts are moving too slowly.

1969

In January, the school board approves retaining the “freedom of choice” desegregation plan, allowing students and parents to transfer voluntarily to schools outside their neighborhoods on a limited basis for the coming school year.

In February, TISD receives a letter from the federal HEW regional office that the Tyler desegregation plan is unacceptable. The board is on notice that a fight is on the horizon: HEW is forwarding TISD’s case to Washington.

The same month, the TISD board approves moving four teachers from all-black Emmett Scott high school to all-white Robert E. Lee High School.

In April, Dr. Martin Edwards is the first black person elected to the TISD board.

Chapter Four: Court-ordered integration hits Tyler

1970s

After years of delay by white school officials, immediate desegregation will be imposed on Tyler schools by U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice. The judge will be hated by many white Tylerites — and considered a hero by many blacks residents — for also forcing out Lee’s Rebel mascot and Confederate regalia and ordering fair elections of cheerleaders at John Tyler High. But one symbol will remain: the school board rebuffs pleas from black students and parents to change the name of Robert E. Lee High School. The black community pays a devastating price in this fight: the school board insists on closing their beloved all-black Emmett J. Scott High School. Go to final chapter or read this history below. See original sources for all entries here.

1970

In March, the Department of Justice (DOJ) takes the unprecedented step of filing a desegregation suit against an entire state, suing the state of Texas and its Texas Education Agency. U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice is assigned to hear the case.

In May, a Justice Department lawyer tells Tyler school officials that the DOJ has received a written complaint, submitted by multiple residents, that black children in Tyler schools are being deprived of their constitutional rights. The decision by local families to complain to DOJ signals that the Tyler district should soon expect a legal challenge from the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division.

On July 15, the Justice Department files a desegregation lawsuit against TISD in federal court in Tyler. The action asks U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice to order immediate, “total and complete integration,” citing years of delays by Tyler school officials.

Officials from the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare tell the judge they tried to persuade the district to convert all-black Emmett Scott High School to an integrated junior high school. TISD’s lawyer and superintendent argue that Emmett Scott and two other black schools must be closed in any new desegregation plan. The lone black member of the school board hires his own lawyer and asks Judge Justice to accept HEW’s recommendations to save Emmett Scott.

On July 25, U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice hears testimony on the TISD integration lawsuit. An attorney for the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division argues that TISD’s proposal to close Emmett Scott and convert a black junior high and elementary school to limited uses is “racially motivated,” particularly given that the district has asked to keep open older, formerly whites-only buildings. An expert with the federal Department of Health, Education and Welfare testifies that Tyler’s plan does not make financial sense, as it would abandon useable classroom space for 2,000 students while requiring the district to spend money for replacement facilities.

In late July, Judge Justice orders immediate integration following HEW’s plan, including keeping Emmett Scott open.

At a school board meeting, black residents ask to change the names of both Robert E. Lee and John Tyler High schools. Board minute summaries do not record what was said by the black constituents, or how the board members responded. Later in the meeting, board members ask the school district’s lawyer to appeal Judge Justice’s desegregation ruling.

In August, after more negotiations with HEW, TISD asks Judge Justice once more to close Emmett Scott and transfer its students to John Tyler and Lee. This time, HEW doesn’t object, and the judge accepts TISD’s plea. Later, Judge Justice will tell his biographer that he had “ambivalent feelings” about these compromises, “but it did accomplish what I was demanding” — the desegregation of Tyler’s schools — and there was little time to do anything else before the start of the new school year..

Today, many whites in Tyler who remember these events lay full blame on Judge Justice and his desegregation orders for the closure of Emmett Scott. Some blacks, however, believe white leaders forced Emmett Scott’s closing both as collective punishment on the black community for seeking integrated schools, and as a way to keep white children from being sent to black-used facilities in minority neighborhoods. “It was a sad day, sad occasion when we got the announcement that the school would be closed,” said Donald Sanders, a black Tylerite who would have graduated from Scott in 1971 and would later become a Tyler city councilman. “None of the white kids were gonna be shipped to Emmett Scott,” a white 1972 Robert E. Lee graduate said recently. “Of course they shut it down.”

On Aug. 6, a 21-year-old black man named Lincoln Ashford comes to a Tyler school board budget meeting and, with a few others, asks to discuss changing the name of Robert E. Lee High School. Ashford and the others, who say they’re members of a group called the Black Liberation Front, are told to put their request in writing.

At an Aug. 13 school board meeting, an out-of-town lawyer speaking for the Black Liberation Front asks the board to change the name of Robert E. Lee High School. An audience of more than 400 listens in the boardroom, and loudspeakers broadcast the meeting to people gathered outside. The attorney presents the board with a petition from 500 black Tylerites requesting a meeting with school officials to ensure fair treatment of all students.

After listening to the requests, a white board member moves “that the name of Robert E. Lee High School remain unchanged for the present time.” Other white board members ask to delay any vote on REL’s name and the motion is tabled. Halfway through the meeting, about half of the audience in the packed board room walks out, though newspaper accounts don’t say why.

On Aug. 31, after a five-day delay approved by Judge Justice, Tyler schools open for the new school year.

On Sept. 11, Tyler authorities arrest six people and search for two more for a plot to firebomb Tyler school district administration buildings and bus fleet. Smith County’s sheriff says his deputies and FBI agents began tracking the alleged ringleader, Lincoln Ashford, six weeks earlier, since he had repeatedly asked school officials to change the name of Robert E. Lee High School and ran newspaper ads demanding a change. In a house east of Tyler, authorities seize 25 Molotov cocktails. Several conspirators confess, telling authorities that they planned to firebomb the buildings on Sept. 12 during a John Tyler High School game at Rose Stadium. Among those arrested are a 22-year-old mother of three who had been an honor student at Emmett Scott and Tyler Junior college. After failing to get the school’s name changed, authorities say, Ashford had been heard saying that “somebody is going to get hurt.”

Announcing the arrests, the sheriff tells the Tyler Courier Times-Telegraph that the plot was homegrown, isolated and “apparently not the work of any radical or militant fringe.”

On Sept. 24, in one of the nation’s most sweeping integration orders, Judge Justice rules that the state of Texas and its education agency failed to provide equal opportunities for public education without regard to race. He places most of the state’s schools under his supervision for desegregation and orders the Texas Education Agency (TEA) to ensure local districts across the state comply with his desegregation orders. Over 1,100 school districts and two-thirds of all Texas students will be overseen by the judge. The case sets the stage for TEA to take action in Tyler over complaints about school symbols at Tyler’s Robert E. Lee High School.

1971

On March 24, 250 to 300 black students walk out of John Tyler High to protest the school’s cheerleader election. Before the walkout, black students had complained that the election unfairly reserved four positions for whites while giving only two to blacks. The students reject school officials’ explanation that the distribution reflected the percentages of whites and blacks in the school.

On March 29, black parents file a federal lawsuit in the wake of the John Tyler cheerleader walkout. The lawsuit seeks to stop school officials from keeping walkout participants from coming back to school; the district was requiring them to first undergo interrogation about their roles in the protests. U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice grants a restraining order allowing the black students to return to school.

On April 5, a federal judge sentences three men to five years in prison after they plead nolo contendre to conspiring to firebomb Tyler school buildings. Authorities say the group planned the attack because school officials wouldn’t rename Robert E. Lee High School. A lawyer for Lincoln Ashford tells the court “it was all born of frustration.”

On July 11, one adult and three black Lee student representatives tell the school board that Lee’s Confederate-themed symbols are offensive to blacks because they represent segregation and slavery. “Black students at Lee feel the Civil war is fought over and over again each year between September and May,” says parent Rostell Williams. “This is of grave concern to the black community and it burns at our hearts.” Student Ruby Hudson tells the board that Lee’s cannon and Confederate flag “knock down black people’s pride. We don’t like white kids waving the Rebel flag at us,” she says, adding that the cannon seems to say, ‘We’re still behind you, General Lee.’”

In July and August, despite school board opposition, Judge Justice orders TISD to create a 16-member biracial committee to help resolve John Tyler’s cheerleader dispute. He also orders the appointment of two more cheerleaders, saying the fact that a cheerleader election had to be hashed out in federal court “speaks loudly” of the need for community dialogue. The school board had tried to argue that a biracial committee would “serve no useful function.”

On Oct. 14, four students representing black students at Lee present the school board with a petition to change the school’s Confederate symbols and name. Student Pat Raibon tells the board that asking black students to honor the Confederate flag as a school symbol is akin to asking Jewish students to honor Hitler and the Nazi flag. Raibon suggests naming the school after white philanthropist D.K. Caldwell, founder of the Tyler Zoo, saying it would make the school feel welcoming to all students. The board refers the request to court-created biracial committees.

On Nov. 11, several “disturbances” break out among black and white students at Lee. They begin in the school quadrangle after white students chant, “Give ‘em hell, R.E.L.” As black students gather in the quad, a teacher asks the white students to stop the chant. The white students sing “Dixie” and a black student allegedly throws gravel. Another black student allegedly throws a punch, and a brawl ensues. More scuffles break out later in the day. Minor injuries and a broken classroom window are reported. The principal tells the evening newspaper that “students of both races joined teachers in trying to get the fighting stopped.” Police officers are called to the school, but the police chief says they saw no fighting nor “any sign of a fight.”

The next day, nearly 500 Lee students don’t show up for school. Some kids say they were told by teachers to stay away. A dozen police, some in plainclothes, are “stationed strategically” around campus before a 10 a.m. pep rally for the upcoming football game against rival John Tyler. Just before the rally, several hundred white students move to the campus quadrangle near the memorial flagpole. Eighteen black students watch the white students sing ‘Dixie’ and shout what the Tyler Courier-Times describes as “orderly but spirited cheers.”

At the pep rally, ‘Dixie’ is sung again, and black students wave pieces of shredded Confederate flags. Some black students turn thumbs down and others boo. When the American flag is brought into the gym for the national anthem, the paper reports, most students sing along, but about 20 black students “raised their right arms, fists clinched in the symbol of black power.” There is a shouting match between black students and white students, and someone sets off two firecrackers near the black students before relative order is restored. Afterward, about 100 black students stand outside the cafeteria and block the entrance. Tyler ISD officials take photos and videos of the black students “as evidence in the event there had been any trouble,” while “faculty members, backed by city police,” tell the group to go to class. After about ten minutes, the black students disperse.

On Nov. 18, school board members refuse to vote on recommendations from the court-created biracial committees of students, parents, and faculty. The committees had recommended that the school retire Lee’s mascot and and other Confederate symbols, citing recent disturbances at the high school. Several hundred people pack the boardroom, and at least a hundred more stand outside to hear a broadcast of the meeting. One board member says black students don’t deserve the right to ask for changes after the spate of fights at the school.

Tyler newspaper reports of the board meeting don’t mention that those fights began after white students taunted blacks and sang ‘Dixie.’ The news articles do include pointed criticisms of black students. “If the black students had been a little less arrogant, a little less demanding,” board member Vernon Goss is quoted as saying during the meeting, “Compromise would have been accomplished. …You may eventually get a lot of these things, but is it worth it to polarize and alienate your whole community so that a great number hate each others’ guts?”

On Dec. 16, TISD board members meet with Texas Education Agency representatives to discuss Robert E. Lee High School’s symbols. Citing Judge Justice’s order that TEA must ensure school symbols don’t discriminate or upset racial harmony, TEA officials say the district must get rid of Confederate symbols. Refusal would cost TISD accreditation and $800,000 in state funding.

1972

In January, Tyler school board members again meet with Texas Education Agency officials to discuss a complaint TEA has received about Lee’s symbols. A summary of board minutes states that it’s “proved” in the meeting “that the Lee cannon was not a Confederate cannon.” TEA tells Tyler school officials that all other symbols and items in question must go.

On Jan. 14, the school board votes 5-2 to get rid of the Rebel mascot, Confederate flags, ‘Dixie’ fight song, Rebelettes drill team, and other Confederate symbols. They also vote unanimously to keep the school’s name. In the morning, Lee teachers fan out across the campus to strip classrooms and halls of anything that might be seen as Confederate imagery. Officials also make plans to strip away a large mosaic in the school lobby and Rebel symbols on the gym floor. Local newspapers describe some white female students crying, other white students venting, and some students of different races appearing to accept the changes. Some students tell a local reporter it will be hard to come up with a new mascot and symbols that don’t reflect General Lee’s Confederate history.

On Feb. 1, the Bulldog — former mascot of now-closed Emmett Scott High School — leads five other proposed mascots in a second round of voting by Lee students. Lee’s principal refuses to release vote tallies to the Tyler Courier Times, saying only that the top vote-getters, in order, were Bulldogs, Generals, Raiders, Red Raiders and Southerners. He tells the newspaper that another round of voting with the top three mascot choices will be held the next day, and “final approval of the mascot will come from the Board of Education.”

The next day, without explanation, Lee’s principal tells local reporters that Bulldogs have been dropped from the final student runoff vote for the high school’s new mascot. The next mascot vote will be between Red Raiders and Southerners.

On Feb. 3, students pick Red Raiders over Southerners as Lee’s new mascot. Lee’s principal refuses to reveal the final vote numbers, saying only that 125 fewer students had voted in the final round than in earlier rounds of voting. The afternoon newspaper’s article notes that the principal “didn’t know if some students did not vote in today’s election or whether there were that many students absent due to the cold weather.” At Tyler’s Pounds Field, the low that day was 38 degrees and the high was 58.

With the Red Raider mascot selected, REL’s principal tells reporters, student committees will begin choosing the Red Raiders mascot’s appearance, selecting a new fight song, and picking new names for the drill team and the guards assigned to fire the school cannon.

On Feb. 21, the Tyler School Board is told that “by majority vote,” Lee’s student body chose “Red Raiders.” That means new band uniforms without Confederate stars-and-bars are needed, school board minutes note. The board approves the purchase, voting to ask for federal funds to pay for them.

On March 20, a Smith county grand jury issues a report blaming “agitation by black militants both in Lee’s student body and outside the schools” for the November 11 incident, which the panel describes as a “riot.” Newspaper reports from that day had called the fights “skirmishes.” The report claims that the confrontations were the inevitable result of “mixing blacks and whites too quickly, due to the Federal Court Order of Judge William Wayne Justice… The economic and sociological backgrounds of the blacks and whites at Robert E. Lee High School were so varied that a difficult and hypersensitive situation existed when Judge Justice ordered Emmett Scott High School closed and the races mixed at Robert E. Lee High School.”

The grand jury’s report, which three of 12 jurors refuse to sign, rejects the notion that the incident was instigated by “alleged symbolism of the Confederacy at Robert E. Lee ….This was an excuse for causing the riot and other campus disturbance.” The report alleges that TISD officials downplayed the incident in their initial public comments. Only after being summoned to testify, the report claims, did the school officials “admit” it had been “a full-fledged riot.”

The report disagrees with the school district’s view that calling in police during altercations might worsen tensions, calling that attitude “a complete failure.”

On April 11, the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals rules that Judge Justice went too far in the John Tyler cheerleader case and strikes down part of his ruling halting disciplinary actions against students involved in the cheerleader walkout. The appellate court concludes, “It appears that everyone — school officials, black students, and District Court — was wrong to some extent.”

1977

Opening a new battle over inclusion in Tyler schools, Tyler’s school board refuses entry to any undocumented students who can’t pay $1,000 a year to attend school, citing a recent Texas law allowing public schools to charge tuition to children of undocumented immigrants. Hispanic families file suit before U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice. In a landmark 1982 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court will uphold Judge Justice’s ban of the tuition requirement and declare that all children, citizens and undocumented alike, have a right to free public school education.

Chapter Five: Lasting scars and unfinished fights

Early ’90s to today

Racial divides linger in Tyler, along with ghosts of a misremembered Confederate past. Black Emmett Scott alums continue to mourn their school. Some Lee alums still resent the loss of their Confederate school symbols. All these losses, and all the stories told and silenced, permeate renewed debate over the name of Robert E. Lee High.

1994

On Feb. 16, hundreds of Lee students walk out of school over two days after a white sophomore comes to school wearing a T-shirt featuring a Confederate flag and the slogan: “It’s a white thing. You wouldn’t understand.” Teachers declare the T-shirt racially offensive and tell the student to take it off. Students leave classes and gather in segregated clusters in Lee’s courtyard. The incident makes headlines across Texas.

1995

The old Emmett Scott school building — now rat-infested, weed-choked and asbestos-ridden — is red-tagged for demolition at a black city councilman’s request. “Everybody says renovate, but how do you do that without any money?” councilman Derrick Choice tells the Tyler paper. Some community leaders and Scott alumni want the building preserved as an important part of Tyler’s history. Others want it torn down so the underlying land can to be given to Texas College. Scotties’ legacy can be honored, they say, with a historic marker and by re-using the land for a new educational building.

1998

U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice, who along with his wife was largely ostracized in Tyler after his desegregation order, steps down from his full-time judgeship in Tyler and moves to Austin. Among the few cases he keeps under his supervision is the 1970 Tyler Independent School District desegregation case. “I wouldn’t want them to forget me entirely,” he tells the Dallas Morning News.

2004

Emmett J. Scott Park is dedicated at the intersection of Confederate Avenue and West Vance Street. Former Scott students remember with sadness having to trade their maroon and white colors for “Robert E. Lee red and John Tyler blue.” A memorial plaque honoring Scott alumni says the park was originally called Lincoln Park. The park, along with Emmett J. Scott High School, had been strategically located in that spot by an earlier generation of white Tyler leaders to stop black neighborhoods from spreading into white ones.

2009

U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice dies at 89 in Austin. A lengthy New York Times obituary hails him as “the judge who remade Texas.”

2016

Judge William Wayne Justice’s desegregation order placing TISD under federal court oversight is dismissed after 46 years. The school district is declared “unitary,” or fully desegregated. When the case was filed in July 1970, the district was 72 percent white and 28 percent black. There were so few Hispanic students that their numbers weren’t recorded in the official school district census. Nearly 50 years later, the district is 46 percent Hispanic, 29 percent black and 21 percent white.

2017

In mid-August, Tyler Hispanic minister D.G. Montalvo announces on Facebook a campaign to change the name of Robert E. Lee High School. He tells local media that the recent violence over Confederate statues in Charlottesville, Virginia, offers Tyler an opportunity to address racial tension and heal divisions. “It’s the right time,” he says. On Instagram and SnapChat, current students at Robert E. Lee hotly debate the issue.

On Aug. 21, more than 300 people — a bigger crowd than any current school board has seen — pack the monthly board meeting to speak for or against changing the name of Robert E. Lee High School. Forty-six people address the board. “We’ve seen lots of examples of communities who deal with this issue very poorly,” board president Fritz Hager tells the crowd. “As we embark on this conversation, my hope and prayer is that we can do it in a way that’s respectful, in a way that builds up rather than tears down.”

Opponents of change decry political correctness and cultural cleansing, and plead that the name is a touchstone for many Lee graduates. Proponents of change say Tyler needs to look to the future and stop glorifying divisive myths about the region’s past. The final speaker of the night, the Rev. Michael K. Mast, has members of the audience nodding and murmuring amens to his repeated refrain: “Change the name of Robert E. Lee!”

Unlike white Lee students, the Rev. Mast tells the board, Emmett J. Scott High School students never got a say in what happened to their school. White Tyler leaders terminated their school, mascot, and traditions behind closed doors, and Scotties weren’t told until it was too late.

The evening’s 46 speakers are almost perfectly divided on whether or not to change the name. The school board listens to the remarks without comment, in keeping with protocol. The new school year starts the following week.

Written and researched by Lee Hancock. Edited by Tasneem Raja. Note: a previous version of this article incorrectly said last month’s white supremacist protests happened in North Carolina, not Virginia. We regret the error.

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.