Note: This story was originally shared as part of our Out of the Loop live storytelling series.

Buenas noches, señoras y señores. My name is Joshua Silva. I’m a senior at Tyler Lee High School. I play in the marching band. I play alto during concert season, or excuse me, alto during marching season and tenor during concert, just for my band nerds out there who are curious. Apart from the band, some of my most meaningful work that I’ve actually done at Tyler Lee lies with the IDD students.

For those of you who may not know what IDD stands for — IDD stands for intellectual and developmental disabilities. I am the leader and president of a worldwide organization known as Best Buddies. Best Buddies is a program we recently brought to Tyler Lee last year. Like I said, I’m the president of it, and it’s been truly one of the greatest things that’s ever come to me.

The goal of Best Buddies is to create friendships or facilitate them — really, I don’t create the friendship — between students who have IDDs and students who do not.

It was a hot day in May. My leadership team and I decided that we were going to help endorse a new movement known as “Spread the Word to End The Word.”

“Spread the Word to End The Word” is a movement that helps reinforce our communities to stop using the r-word in a derogatory or negative fashion.

Now, for those of you who may not know what the r-word is, the r-word is retard or retarded. This may sound like common knowledge in 2019, really, not to call anyone that. But sadly, it’s a lot more widespread than you’d actually think.

We took a very unconventional route as to how we’d approach this. You know, most places would probably just get some flyers and put them up on the school.

But you know, when you’re in high school, everyone’s angsty, everyone’s angry all the time. So “I’m going to rip this paper because it’s what my heart tells me to do.” So that’s what we figured people would do, so we took a weird route to gather people’s attention.

We got three stationary bikes, the kind that don’t go anywhere, placed them outside of our east cafeteria, right in front of our courtyard, where everyone would be watching us — and wore these weird biker outfits that consisted of Racquet and Jog shirts, tight shorts and helmets with Mohawks.

And we basically called out our message to the gathering crowds. I was very uncomfortable to say the least, guys. So as we did this, we announced our message. We gathered people’s attention and — should they agree with us and they approached us — we had a poster that was right behind us on a brick wall.

And if you agreed with us and our message and what we were saying, you know, you would walk up, you’d sign the poster and say, “Hey, I agree with you,” and we might let you ride the bike.

So some walked by and, you know, were really motivated and passionate and agreed with us. Some simply smiled and went away and others didn’t even bat an eye as they had their headphones in blasting at 10, with whatever song they were listening to. All seemed to be going really well, actually.

Until I met a particularly intense guy. He walked right up to me, face was dead set. He stared me right in my eye. And he said, “Why is it so bad to say that word?” I didn’t really think much of it. Actually, I’d been announcing this to like 400 people for the past two hours on this bike. It was hot and I was sweaty.

So I told him what I had been telling everybody else. “The term is, the r-word is something that we use to denounce each other, like ‘stupid’ or more which, I mean, everyone does, but this word actually causes a lot more pain and hurt than you would actually realize, and it’s not something we need to continue to endorse anymore.”

He completely, like in one ear out the other, and stared, continued at me and said, “Yeah, why does it matter? What if no one around me is actually mentally disabled? And even if they were, it’s not like they could understand me.”

I bit my tongue. I was a little upset, but I just continued on and I told him, “That’s not the point.

“One, it’s common courtesy that we need to respect others and what we say, knowing that it could hurt people. And two, whenever we continue to use this word, all it does is endorse this standard in our community of ignorance and hurt.

And worst of all is, you never know if someone’s truly mentally disabled. They could be on the lighter end of the spectrum. And you may never even notice.”

Unsettled, completely unfazed. He stared me in my eye again. Eyes are locked in, and he said, “Well, that’s retarded.”

My heart dropped. I didn’t know what to say. I was overcome with guilt, a lot of pain, because as he said this, he walked away and I didn’t do anything.

I was filled with guilt because I felt like I had failed. I felt like I’d failed in defending my IDD students because I didn’t say anything. I didn’t know what to say.

I got up and walked away. I didn’t know what to do. I felt like I had failed my program. I had spent an entire year endorsing Best Buddies and working with Best Buddies because I thought I was making a change, because I thought I was doing something for the better. And here I was faced in a situation where you seem to be stuck where we were before.

And worst of all, I felt like I had failed my sister, which brings me to the heart of my story.

Like many of you, my story begins with my family. I come from a blended family. It’s me, my stepdad, my youngest sister, Emma, my second youngest sister, Alyssa. We recently moved to Tyler three years ago. My dad received a promotion through Suddenlink —shout out to them.

A little over a year ago, we’ve recently said our goodbyes to my second youngest sister, Alyssa, who I’d never been away from for more than two weeks.

Alyssa had been in a lifelong, ongoing battle with that epilepsy. And then over the past, the last two years of her life, she had been facing a battle with psychosis.

It took a tremendous toll on my family and I didn’t know how to cope. I didn’t know how to feel. I felt like I lost my purpose because without my sister, I didn’t know who I was or what I was going to do. I was lost.

It wasn’t until after a summer of mourning that once my junior year began, I decided to take my first step forward in honoring her legacy and preserving it.

I realized that AP Physics is not where I belong, and I dropped the class, and I had a free first period. I joined the life skills classroom or special ed room as a volunteer student aid.

I met a man named Austin Doyle. He’s our special education coordinator at Tyler Lee, and he introduced me to probably the greatest program in my lifetime, and it was Best Buddies.

Best Buddies is not just, not only been just my lifeline, but a breath of fresh air for Tyler, y’all. Best Buddies is something we’ve used to help endorse and embrace inclusion and acceptance and integration in our community.

It’s been something that helps endorse change for the better for everybody. I’m very proud, very proud to be in it. Very proud of the work that we’ve done.

See throughout this year, I’ve learned a couple of things, actually. One, you can’t change people. You can’t change them. It’s something they have to choose. Now you can definitely influence them. I’m not saying that, but they have to choose it for themselves.

Two, I realized I didn’t fail that day. I would have only failed had I given up. If I had given up at that point and stopped supporting my IDD community, I would have failed if I had stopped trying to help them, if I had just left.

Before God and before all of you, I promise no matter where I am physically or in life, I will never give up. I will never give up on them, because I know they’ll never give up on me, either.

Third, I realized that the heart and soul and the future of IDD doesn’t lie within just me. It doesn’t. It lies within all of you, actually. Whether you realize it or not, you’re a part of this. Tyler, Texas, is the first town east of Dallas in East Texas to host a Best Buddies chapter. We’re the first one.

You guys are all a part of it, from our local businesses to our people, everybody who’s helped support. You’re all a part of it. Every time you stop someone from saying that word, from hurting somebody else, you’re supporting inclusion, you’re supporting acceptance, and you’re supporting embrace. You’re all a part of it.

And Tyler’s a great, beautiful community to start this movement. I’m glad that we’re here. This reminds me of a story.

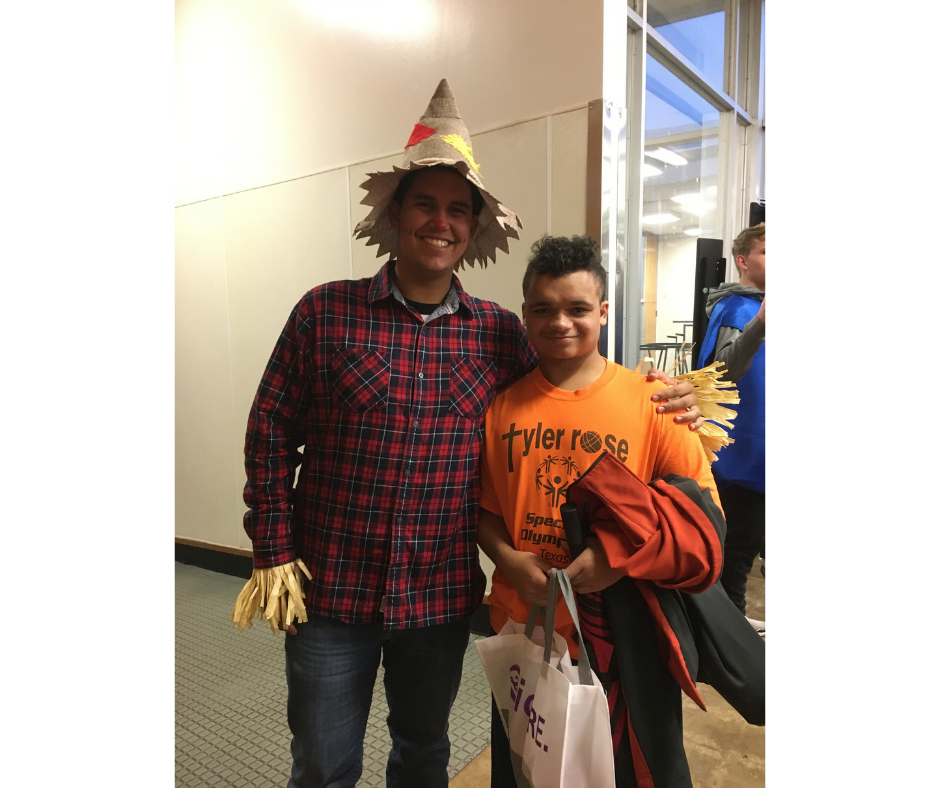

Last year, we got endorsed for a Friendsgiving event at my house, where we hosted Thanksgiving to our life skills students and to our general education students alike, so everybody came.

We all got to stand together, listen to music, enjoy each other’s company, dance. The highlight of the night for me was we all stood in a circle, held hands together and we prayed before we ate.

I promise y’all in that moment, I felt my sister there, and I felt her grace. And I was so happy because I realized I didn’t let all that knowledge she taught me in her 14 years in life just go to waste.

Before I go, I want to leave you guys with these words. Integration is being asked to the party, but standing alone. Inclusion is being asked to dance.

Here in Tyler, Texas, we’re dancing, y’all. Thank you.

Joshua Silva is an undergraduate student at the University of Texas at Austin, studying to become a special education teacher. Born in California and raised in Texas, Joshua loves to play the saxophone and is passionate about special education and the pursuit of equality for the disabled community. He loves working with children at Tyler’s Best Kids, an after school program. He would like to dedicate his accomplishments and educational pursuit to his beloved sister, Alyssa, who passed away in 2018 and inspired Joshua to impact IDD communities. Joshua was appeared in The Tyler Loop’s COVID Stories video series.

Have a true personal story about life in Tyler and East Texas you’d like to share at the next Out of the Loop storytelling event? Email storytelling director Jane Neal and describe your story in a sentence or two.

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.