Statues of confederate generals may crumble to dust and the names of public buildings can be changed, but Tyler will never lack proof of racism’s power in the community. That will forever be documented in files maintained at the Smith County courthouse.

A month-long search of thousands of county property records shows that the city’s segregated neighborhoods did not happen by accident but through the use of racial deed restrictions designed to keep Blacks and whites separated. For over 25 years, the racial covenants were used to keep entire subdivisions white or, in at least one case, Black.

Racial covenants began to appear in the early 1920s, not just in the southern United States, but across the nation. In a 1926 case, the Supreme Court ruled such covenants legal.

Then in 1947, the court ruled that the covenants were not illegal but that they could not be enforced by any arm of the government. By that time, the federal Commission on Civil Rights estimated in 1967, fully 80% of all residential property in Los Angeles and Chicago was governed by racial or ethnic covenants.

The property records reviewed by The Tyler Loop do not indicate such a high percentage, but those records do not take into account any private agreements that may have existed between homeowners in different neighborhoods. The covenants were only completely made illegal by the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Crescent Heights Garden, a North Tyler “rose” community

A drive down the streets of the Crescent Heights Gardens subdivision in North Tyler provides all the proof one needs that it is an eclectic neighborhood. The original subdivision included 150 lots for houses on Crescent, Englewood, Confederate and Cochran streets.

Old homes — some badly deteriorated, others well-kept — dominate the streets, which could use some repair. Most of the people who live here are not nearly as old as the houses, ranging from grandparents to new parents. Scattered across several lawns, toys for toddlers await the return of their children. The racial make-up is equally diverse.

This is not at all the way John Luther Tyler and his wife, Pearl Patterson Tyler, planned it in 1935. They had hoped to build a homogenous middle-class neighborhood with all white residents. To add a touch of uniqueness, the deeds mandated 24 rose bushes in every front yard. With 150 lots in the original plot, that would have put 3,600 rose bushes in the neighborhood. The deeds did not specify a required color for the roses.

Today, no roses can be found on Crescent Drive.

John Luther and Pearl Patterson Tyler created Crescent Heights Garden using property that had long been in the Patterson family. Confederate Avenue may have been named partly to honor the memory of Pearl’s father, who lied about his age to join the rebel cause.

It is not clear how many people who live in the area know that the covenants were ever written into the deeds for their property. Several people — all of whom would have been banned under the covenants — indicated that they had no idea.

Ashanti Jones, who identifies herself as an “independent activist” and who began the petition to change the name of Confederate Drive, said she had never heard of racial covenants.

“Why did they do that?” she asked. She was not the only person of color to pose that question.

Crescent Heights Gardens is far from the only subdivision in Tyler that was originally designed to be “all white.” Other subdivisions — by no means a complete list — include Bergfeld, Bergfeld and Durst, Park Heights Circle, Donnybrook Heights and Connally Heights additions.

A middle class segregated neighborhood

The Tylers had no plans for an elegant subdivision with palatial homes in getting plans approved for Crescent Heights Gardens. With construction starting in 1935 in the midst of the Great Depression, the couple must have known that few people could afford a grand home.

Still, they did set minimum standards that would have precluded some buyers. Most of the lots required brick or brick veneer construction. No houses fewer than 1,000 square feet would be allowed and the subdivision required houses to cost at least $2,000 to $3,000 to build. That range in today’s dollars would be $37,600 to $56,400, firmly in the middle class range of homes.

As with racial covenants in Tyler, homeowners of Crescent Heights Gardens were restricted from renting, leasing or allowing anyone who was Black to live on the property.

Planned segregation

Not only were Blacks not allowed in “white” subdivisions but at least in one case, whites could not live in a subdivision that was deemed exclusively for Blacks. The difference in the way the two racial covenants were written was substantial, however.

Blacks could not own property in Crescent Heights Gardens for any reason but in College Park Heights — adjacent to Texas College — whites were allowed to own property for “speculative” purposes, according to the deeds.

Whites were not only not allowed to live in College Park Heights, but all the businesses there had to be owned by Blacks and no whites were even allowed to act as clerks or helpers in the stores.

The restriction — on every deed transaction made in College Park Heights — was specific. “All residence lots in College Park are reserved exclusively for the residence of the colored race. All businesses are to be conducted by the colored race…. The Caucasian shall be permitted to purchase lots for speculative purposes but to be used only by colored people.”

College Park Heights was also the only subdivision checked in Tyler that specifically prohibited prostitution — already illegal by state law — as well as gambling and dance halls.

The subdivision was approved in 1932. Only two races were recognized in the deed records checked, white and Black. We found no residency restrictions for those of Jewish descent, though such covenants were common in large cities such as New York.

There was no single way the deed restrictions were written. For instance, a lot in the Durst and Bergfeld addition in 1938 was sold to Dr. R.L. Page with the clause that the property would “never be sold to or occupied by a person of African descent.”

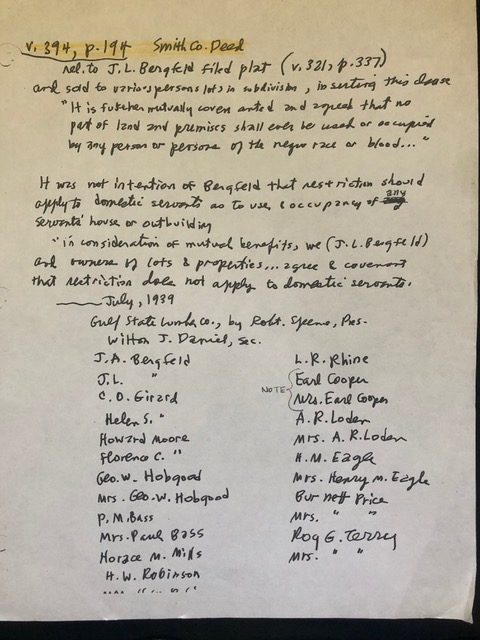

That same year, in the J.L. Bergfeld addition, T.F. Crocker bought land with the understanding that “no part of said land and premises shall ever be used, occupied by, sold, leased or given to any persons of the Negro race or blood. This shall not apply to domestic servants who may occupy servant’s quarters or out-buildings.”

In one case, the restriction called for no person other than one of “Aryan” descent to occupy the property.

Can anything be done?

Racial or religious deed restrictions carry no force but the process for removing them in Texas requires getting approval from those who live within a subdivision. Depending on the subdivision, that can be a time-consuming and costly task.

Even if other property owners agree, the change does not affect documents already filed in the County Clerks office. Those cannot be changed and remain as proof of the challenges imposed on people of color who came earlier in the city’s history.

Usually, the racial restrictions are not specifically cited in property records after 1960; however they will remain on the original deeds forever, bearing witness to what has gone before.

Tyler Councilperson Shirley McKellar, who represents District 3, where the Crescent Heights Garden subdivision is located, said she would support finding ways to remove the deed restrictions if that was what the residents wanted.

“They (the restrictions) would have to affect the owners,” she said. “Particularly those who want to sell the property themselves. I have heard of people who didn’t understand these things and eventually just wound up just walking away from their property.”

Since the covenants are no longer legally binding, McKellar said property owners would probably be more effective at using their energy to change other kinds of conditions that beset Tyler.

She said she is particularly worried about the recent violence that has occurred during peaceful demonstrations held on Tyler’s downtown square, such as the confrontation between those protesting actions in Portland, Oregon, and a “Blue Lives Matter” demonstration.

“I was in downtown Tyler when that happened. I got down there and saw all those people with long guns and I felt like I was back in a war zone,” McKellar, a veteran of the Iraqi war, said. “We can’t allow that to happen again. If we don’t take care of that we are going to have a real problem someday.”

Many who live in Crescent Heights Garden today are Latinx and were not excluded from living there in the original restrictions.

Dalila Reynoso, who ran against McKellar for the city council position and is a leader in the Latinx community, said property owners need to consider priorities when looking to make any changes. That includes the effort to change the name of Confederate Avenue. While she joins McKellar in supporting that change, neighborhoods have other serious needs.

“I block-walked in that neighborhood,” Reynoso said. “It turns out that no one had ever knocked on their door to ask them what they wanted. There are many other needs. For one thing I believe that when law enforcement shows up in some neighborhoods, it isn’t pretty.

“We really need to ask ourselves, ‘What can we do to add value to these neighborhoods?'”

Phil Latham has been an East Texas journalist for more than 45 years as a reporter, editor, publisher and editorial page editor. He writes a weekly column available at https://platham56.wixsite.com/website. He has also written two novels. Readers can contact Phil at [email protected]. He lives in Smith County with his wife and three pups.

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.