At 6:30 a.m., Judson Barneburg and Sonia Arzola clock in to work at the zoo. They tune the radio station to 106.5 Jack FM, tie aprons on over their blue polos and khaki pants, walk into a freezer, and start hauling out ingredients for hundreds of meals. Taped to the freezer is a grocery list: 1,000 pounds of produce; 400 pounds of fish; 250 rodents; 7,000 crickets; 80,000 worms, and so on.

Over the course of the day, these ingredients will serve as a delicious buffet for the 3,400 animals that call Caldwell Zoo home. Barneburg, 49, and Arzola, 52, are two of the zoo’s most experienced chefs, carefully crafting each meal to each animal’s needs and tastes. Per month, the commissary spends $26,000 on food, totaling $312,000 a year.

So who’s got the biggest appetite? That would be the zoo’s three elephants, who each eat nearly 100 pounds of food a day. And the smallest? A cadre of 50 Madagascar hissing cockroaches, who share two daily pieces of dog food and one orange slice.

“It’s an animal restaurant and animal kitchen,” Barneburg says. “But they don’t get to order what they want.”

Barneburg and Arzola spend the first four hours of their shift prepping the animal’s diets for the next day. Nodding along to 80s radio hits, they slide bowls across the table to each other, weighing how much seed is in one, how much fish in another. Arzola teases Barneburg, telling him he’s lucky he has such reliable people to work with.

Arzola worked with Evon Brooks, who created Caldwell Zoo’s commissary in 1953, and has worked in the commissary for 35 years. She jokingly says she and Barneburg are married, having worked together for 33 years, five days a week, eight hours a day. She tells him she’s her own boss, despite Barneburg’s formal title as head of the commissary, and he doesn’t deny it. “Except when I want days off,” Arzola laughs.

It’s Barneburg’s job to figure out the nutritional needs of every animal, from how rabbits each lion gets, to which months of the year the alligators actually need to be fed.

As for the massive shopping list on the freezer, Barneburg has his sources. He buys regionally whenever he can, from vendors like Ben E. Keith, a restaurant-food distributor based in Fort Worth. Caldwell Zoo typically gets two shipments of produce a week, and insects once a week. Meat, including frozen mice, rats, and rabbits, comes in every two months and is stored at -10°F.

In 2018, when an E. coli outbreak was linked to romaine lettuce, the main leafy green for many of the larger herbivores, the commissary was quick to act. They immediately threw out all the romaine in the zoo and searched for the best nutritional substitute, landing on green-leaf lettuce. Barneburg says big scares like this don’t happen often, but when they do, he and Arzola are ready for the challenge.

Everything in the commissary’s kitchen is oversized. There’s a huge stove with a pot large enough to boil dozens of eggs or sweet potatoes at a time. “It takes two of us to put it on the stove with water,” says Arzola.

“It’s just like cooking at home!” says Barneburg as he placed chopped vegetables in a bowl alongside a boiled egg and frozen mealworms that are starting to wriggle back to life.

Eating the same thing every day gets boring for humans, and animals aren’t any different. That’s why Barneburg and Arzola make “rotational diets” depending on the week or the day. For example, bears get blueberries twice a week. Today, they’ll get pasta. The squirrel monkeys are getting sunflower seeds, but tomorrow, they’ll get peanuts. It’s a way to make sure the animals get all their nutritional needs met, but it also provides variety. The zookeepers and commissary workers call that “enrichment”—attempts to stimulate the animals into performing “wild” behaviors.

Each bowl is carefully weighed after a new ingredient is added. Arzola stresses the importance of each ingredient’s weight. Giving an animal the wrong amount of nutrients can lead to fur issues, feather loss, and even metabolic bone disease.

Still, Arzola and Barneburg acknowledge trying to get each animal the exact perfect amount of nutrients at every single meal is next to impossible. Caldwell Zoo has several “communal” living spaces, where different species of mammals, birds, and fish coexist.

“It’s a buffet out there,” Arzola says. “We weigh everything out according to what they get, but we can’t stop them from eating other animals’ food. They just take what they want.”

And that’s not accounting for one of the commissary’s biggest enemies: local food thieves. Wild ants, possums, squirrels, and raccoons are prone to stealing food right out of the outdoor exhibits. The zoo has Animal Control on speed dial.

Black Bears

The zoo employs about 85 full-time zookeepers, 120 in the summer. Each keeper feeds about 50 animals a day. Around 6 a.m., commissary employees load various animals’ meals into coolers and transport them to the zookeeper’s different areas—like the Wild Bird Walkabout or the reptile house—so the keepers can feed the animals first thing in the morning, and later entice the animals back to their pens at night.

At 8:30 a.m., zookeeper Erin Francey picks up her cooler of food and unlocks the two heavy chain link gates that lead into the empty bear exhibit. She’s already fed the squirrel monkeys and the meerkats. The two bears, siblings Timber and Tyler, are still in their concrete holding pen, a small building behind their exhibit that serves as their bedroom during the night.

Human children get scolded for playing with their food, but Francey wants the bears to have as much fun as possible. She takes two large mushroom-shaped objects and pours bear-feed pellets into them. Francey has dubbed these toys “amazing graze.” They force the bear to knock and tumble them around until the food falls out, rewarding them for being “more bear-like.”

Francey then walks around the rest of the exhibit with handfuls of cooked pasta and vegetables, hiding it under massive logs and rocks and placing some along the artificial river running through the cage. Making the bears “work for it,” Francey says, is what makes the bears’ life at the zoo interesting and active.

“It seems simple, putting out food, but this is a way that we can really make their lives better,” Francey says. “Even though it just seems like we’re putting out lettuce or orange slices, it’s really something that makes them more bear-like when they’re not in the wild. The best thing we can do for them is to give them as best a habitat they would normally have. That’s really what makes the difference for me.”

Francey stuffs a little more pasta under the rocks and opens the pen, ushering Timber out. The bear ambles over to the amazing graze toys. The brown pellets within, Francey explains, are her favorite. Timber shakes and plays with the toys for several minutes before pellets fall out and she begins to enjoy her feast.

Sulcata Tortoises

“They tend to sit right in the middle of their food and eat,” keeper Kaley Sullenger says, lugging a five-gallon-bucket full of hay, grass, romaine, mixed spring greens, squash, and carrots. They’ll get half of their food in the early morning before the zoo opens, and the rest later in the day.

Slow and steady wins the race when it comes to tortoise gastronomy. Brothers Trey and Speedy, both 26 years old, toddle their way slowly from their hut to the feeding block. But their current speed is deceptive.

“You’ll never see a tortoise run faster than when there’s a watermelon in that pond and they all come stampeding towards you,” Sullenger says.

Watermelon is the tortoises’ favorite. They get it once a month during summer, specially delivered from the commissary as part of their enrichment. The keepers always serve watermelon in the pond, because if juice gets on the dirt, the tortoises will eat the dirt just to get the flavor. Then, each tortoise gets a bath to wash all the watermelon juice off of them, “just like two-year-olds.”

“Watermelon days are the best days,” Sullenger says.

Elephants

Caldwell Zoo just recently got two new nine-year-old elephants, Emanti and Mac. Along with Tonya, the 43-year-old matriarch of the trio, they have the biggest, and most expensive, appetite in the zoo.

Zookeepers Jesse Santee and Kara Leigh start feeding the elephants as soon as they get to work around 7:30 a.m. It takes them an hour to prepare the nearly 200 pounds of food they’ll later scatter across the yard.

In the mornings, the elephants get grains inside their pens, a custom blend made specifically for Caldwell’s specification by AC Nutrition, an animal-nutrition company based in Winters, Texas, as well as alfalfa pellets. Chomping on the grains and pellets distracts the elephants while Santee and Leigh fill eight hay feeders around the exhibit. The elephants have a bad habit of hoarding food and eating too fast, and the hard-to-reach feeders help force the elephants to slow down and share.

Santee and Leigh also place branches, at least ten- to twelve-feet long, on the ground around the exhibit. These were cut from the “Back 40,” undeveloped land behind the main zoo owned by Caldwell. Every day, they cut enough of these branches to feed the elephants, giraffes, primates, and many other animals in the zoo.

Lastly, they take three buckets, one filled to the brim with celery, cucumber, romaine, sweet potato, and carrots, another with bran, and the third with rehydrated beet pulp (to “keep the elephants regular”), and literally throw the contents across the yard and into the pond, making sure the elephants will swim and exercise to get their food.

“The more we scatter, the more opportunity everybody has,” Leigh says, climbing a fence post and dumping a fistful of rehydrated beet pulp on top.

Elephants get bored easily, so enrichment, usually in the form of food and training, is an absolute need.

“You have to have tons of enrichment for elephants because of how smart they are,” Santee says. “They get daily enrichment, stimulating all five senses. It’s all day, every day.”

Leigh works with the elephants at the “training wall,” where they instruct the new boys to do tricks and exercises. Emanti and Mac are then rewarded with another bucket filled with treats like onions, bok choy, squash, bell pepper, and radishes.

“Coming in, day after day, just to work with them is the biggest privilege, cause they’re so much fun and they’re so smart and so intelligent,” Leigh says, “As much as we’re trying to teach them, they’re teaching us a heck of a lot more. It’s a whole lot of fun.”

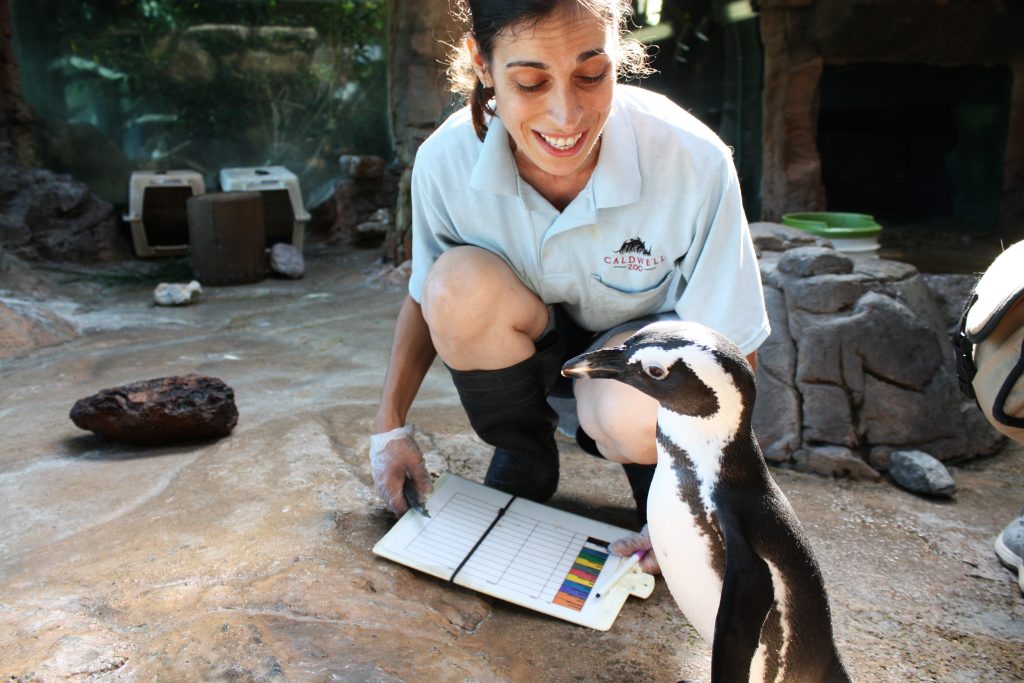

Penguins

The zoo’s African penguins are probably the pickiest eaters at the zoo. Zookeeper Whitney Geslois says Taz is the perfect example.

“He likes firm fish; they can’t be too soft and they can’t be too hard,” Geslois says. “He only likes capelin. He won’t touch the herring. Some penguins only eat capelin, some only eat herring. It depends.”

Each penguin eats about a pound of fish a day over the course of three public feedings. The keepers hand-feed the penguins so that they can keep track of how much and what type of fish they eat.

“It’s very important for us to know if they’re eating less. That’s a sign that they’re not feeling well,” Geslois says. “If they’re eating more, maybe they’re preparing for their molt.”

Geslois has worked with the African penguins for the six years she’s been at the zoo. These penguins are critically endangered; wild populations are expected to disappear within the next hundred years. For Geslois, that’s made working with this species personal.

“It hits me every once in a while that this is my job, to take care of these guys,” Geslois says. She knows each of them by name and personality.

“Wangari is a very sweet penguin,” Geslois says, as she tries to stop another penguin, Duncan, from biting at her shoelaces. “This time of year, Taz has a very territorial personality. Jeff has a strong personality, Duncan has a strong personality.”

Back at the commissary

As their shift comes to an end, Barneburg and Arzola begin to disinfect everything with bleach and prepare for the next shift to come in. They’re quiet and focused on their work. “I would feel so bad if one of the animals got sick because I didn’t do this or that,” says Arzola.

Caldwell Zoo is a member of the American Zoological Association, a non-profit organization dedicated to overseeing top-quality animal care, conservation efforts, and educational experiences in zoos across the nation. Caldwell participates in the organization’s Species Survival Plan, with special breeding and conservation programs dedicated to preserving critically endangered or threatened species. Caldwell played a crucial role in keeping the Attwater’s prairie chicken from going completely extinct—though Arzola and Barneburg dread the task of chopping up the peas and greens as thin as the prairie chicks require.

This year, Caldwell is up for reaccreditation by the AZA Accreditation Commission. In the winter, AZA agents will visit Arzola and Barneburg’s commissary, observing how they prepare food, ensure the quality of their ingredients, and balance nutrition, especially for endangered animals.

“To me it’s all the same,” Barneburg says. “You’ve got to take just a good of care to each animal, no matter if they’re considered threatened or endangered, or if they’re prolific.”

Barneburg and Arzola gather the dry ingredients they’ll need to prepare tomorrow, and begin to do the dishes. One of them begins to prep the lettuce used at the giraffe feeding station. For every animal that gets released into the wild after rehabilitation, or as part of the species survival plan, they know they were a part of that animal’s life and care.

Tomorrow at 6:30 a.m., they’ll clock in again and start chopping, measuring, weighing, and cooking, “with love, every day.”

Reporting by Claire Wallace. Photography by Yasmeen Khalifa.

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.