As a friend and I lamented our nation’s disjointed responses to the coronavirus, she declared, “It’s like we’re making the same mistakes we made before!” Those words have stayed with me.

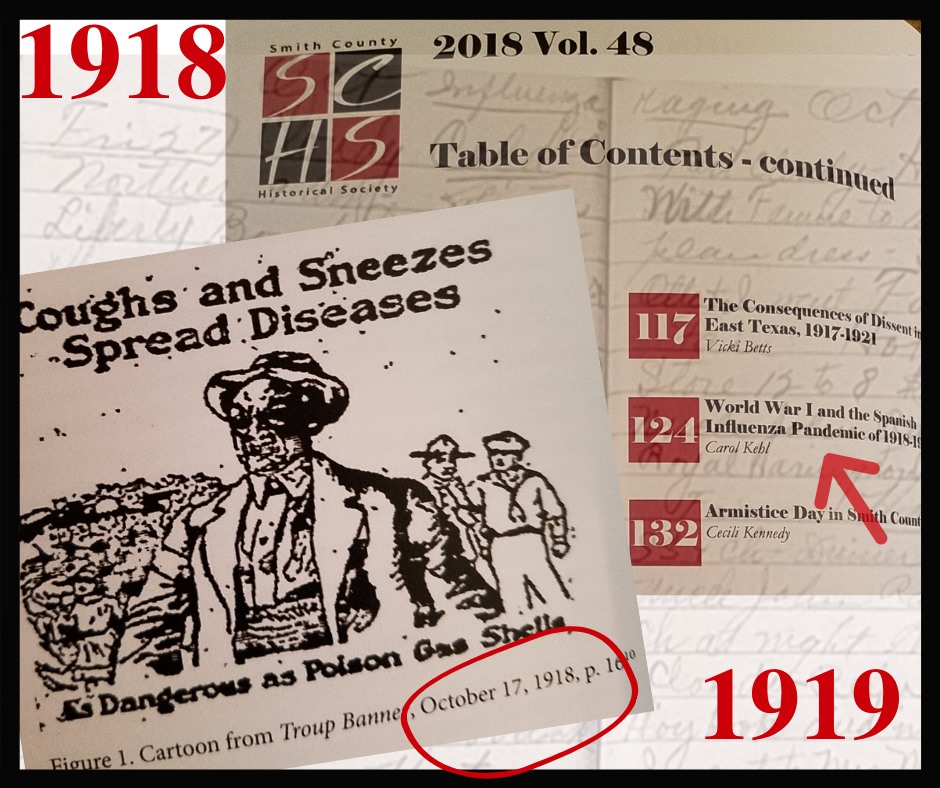

In 2018, Carol Kehl wrote an eight-page article, “World War I and the Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919,” in the Smith County Historical Society’s Chronicles of Smith County, Texas, Volume 48. What would have been interesting reading last year is now riveting, uncannily timely.

Like now, wearing masks in public, staying home, disinfecting surfaces, watching an economy plummet and the death toll rise became part of daily life in East Texas during the 1918-19 flu pandemic. So did case undercounts, misinformation and media downplays.

The first global wave in the spring of 1918 did not receive much attention in Tyler and Smith County. But by the fall of 1918, the second and most severe wave reached the Piney Woods, wreaking havoc, particularly on people aged 18-43. Then, in January 1919, the flu’s third wave again caused sickness and death in East Texas.

Here are excerpts from Kehl’s well-researched article, chronicling measures taken, diary entries and lives lost. Side-by-side Kehl’s account is our current coronavirus news. Yesterday, May 31, the Texas Tribune announced that “Texas reported 1,949 more cases of the new coronavirus Sunday — the highest increase since the state began reporting coronavirus case counts.”

It gives pause to ask, “What might we gain from studying our response to the last pandemic?” and “How will the COVID pandemic of 2020 be remembered by our East Texas successors?“

Special thanks to Tiffany Wright of the Smith County Historical Society for helping The Loop access these print and photo archives while the museum’s doors remain closed.

Global travel creating mass spreads of infection

“Trains loaded with troops traveled through Tyler and often made stops at the depot where Red Cross volunteers operated a canteen. Soldiers were contracting the flu at training camps like Camp Travis in San Antonio, and would then visit home.”

Local protocols

“As preventative measures, citizens of Smith Co. were warned to avoid draughts and sleeping in the same room as the patient, to avoid crowds, not to stir up dust and to use wet cloths to clean the home.”

“Dr. Courtney Clark, City Manager of Troup, Texas, ordered the picture show closed.”

Questionable remedies

“Tyler City Manager Henry Graesen visited merchants, suggesting the use of a mix of bi-chloride of mercury and water to clean floors and sidewalks.”

Rising cases and death tolls

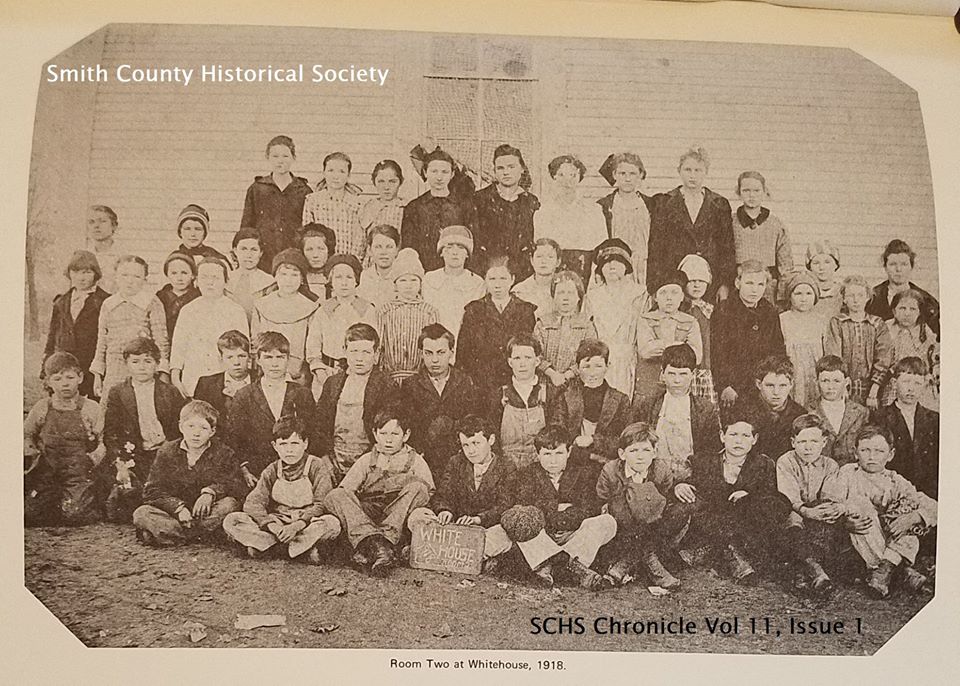

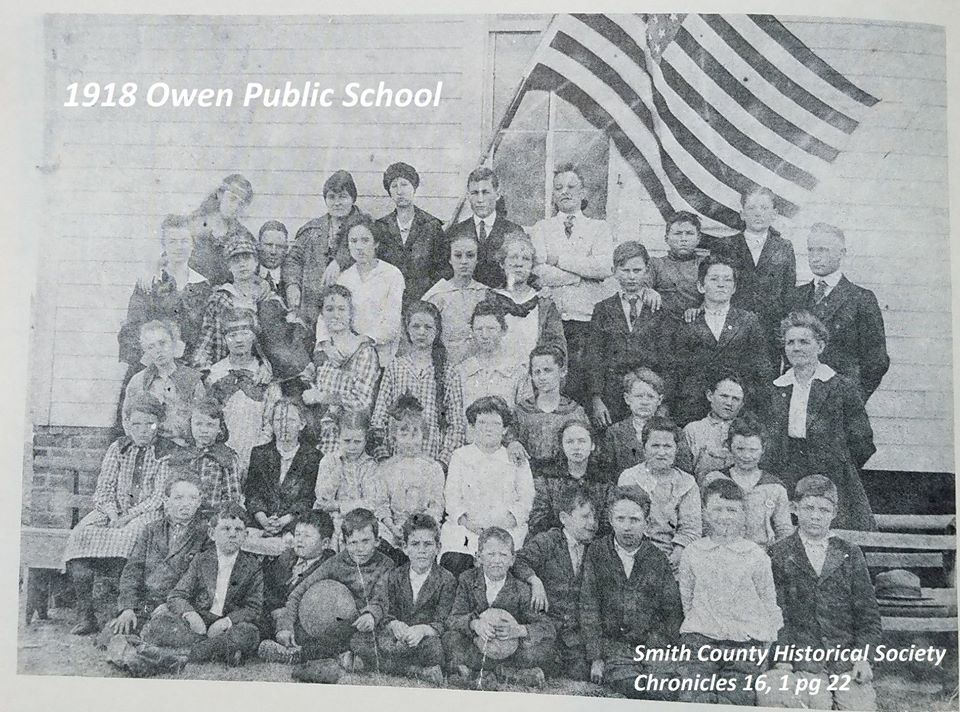

“Deaths from the 1918 flu were reported in Tyler, Lindale, Troup, Gladewater, Winona, Whitehouse, Arp, Omen, Flint, Overton, Mt. Sylvan, Swan and rural communities.”

Kehl notes that local resident Hattie Earle Mathis kept a diary in 1918. Across the top pages in the month of October, she wrote, “Influenza Raging.”

“On November 5, 1918, the number of flu cases was 899, with 18 deaths. “

By January 1919, the third wave arrived in Smith County. A total of “1,367 and 25 deaths in Tyler” were reported during the first months of 1919.

“The flu killed school children, teachers, farmers, housewives, laborers, machinists, ministers, railroad men, business owners and washwomen,” seen in Kehl’s scans of local death certificates.

Undercounts

“Smith County records for the number of citizens who suffered are incomplete. Some of the Texas death certificate records do not indicate an attending physician or cause of death. It is unknown if physicians used the same criteria for diagnosing illness. It is probable that some residents who had the flu were not attended by a physician.”

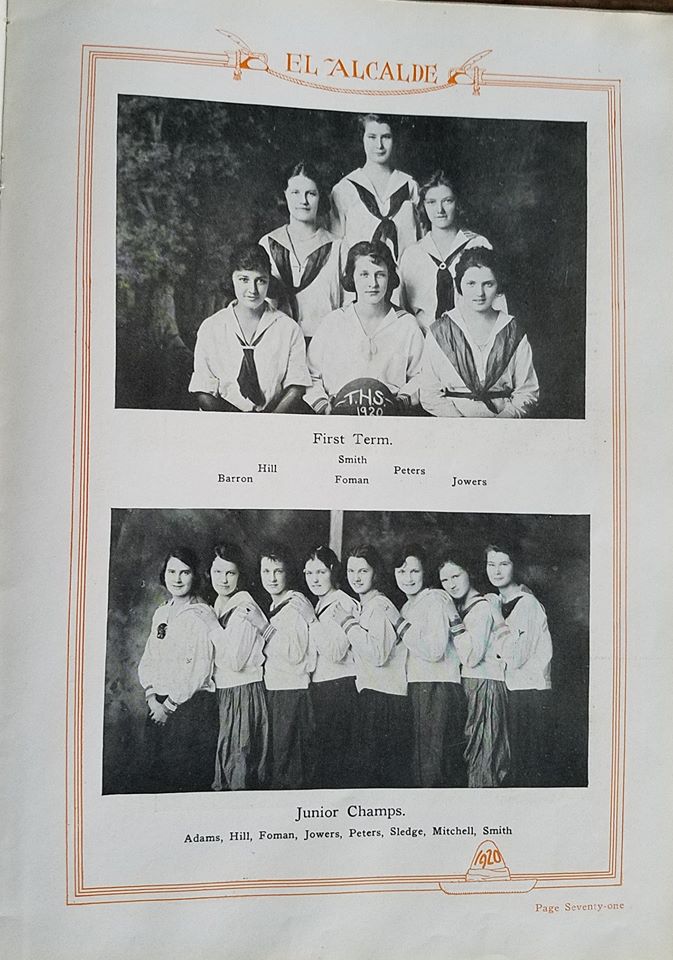

A School Year Disrupted

“Superintendent Shelby reported ‘a total of 386 pupils out of high school and eight teachers out on Monday.'”

Kehl’s article mentions Alma Moore Freeland, a high school student in Tyler in 1918. She wrote, “I was the first in my family to contract the disease, which was to drastically affect my scholastic career as well as my health. The pain was indescribable, and not one inch of my body escaped it.”

Local first responders

“In Tyler, physician D.D. Rice supervised female instructors who offered 18 classes in first aid.”

Local journalism

On November 7, 1918, the Troup Banner announced the flu’s end, while simultaneously reporting how families were still suffering:

“…the entire family would be sick of flu to such an extent that one would not be able to wait on another.”

The Troup Banner also published a poem, “The Flu,” including these lines:

“It thins your blood and bends your bones

And fills your craw with moans and moans.

And sometimes, maybe, you get well.”

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.