“Where do you worship?” It’s a question I’ve been asked over my 13 years in Tyler at the workplace, poolside, park and grocery store.

No surprise, as I live within walking distance of five churches. One of those is Green Acres Baptist Church, which boasts more than 16,000 members — a whopping near-15% of Tyler’s 109,000 population.

Further, Tyler’s religious rating soars at 73.2%, more than 15% higher than Texas’ overall religious rating.

In a land abounding with churches, church-affiliated coffee shops, Christian-themed breweries and 245 Christian nonprofit organizations, who are Tyler’s nonreligious residents, eschewing identity and membership with a religious institution?

The Tyler Loop reached out to six such residents. Four of the six interviewees requested an alias for anonymity, citing potential professional or family repercussions if their names were revealed.

To learn about their upbringings and decisions to leave religion, read on. And look for a similar, companion story about East Texans devoted to their faith tradition, coming soon.

Stephen Hidalgo is a 70-year-old Tyler resident, enjoying a second creative career in library services.

Raised Roman Catholic, Hidalgo’s mother made sure her children went to mass every Sunday. At age eight, hospitalized following severe burns, a nun visited Hidalgo. “Very soon after that, I told my parents I was going to be a priest,” he said.

Hidalgo’s devotion did not wane in the following years. “I was going to become a religious and take vows of poverty, chastity and obedience,” he said.

In 1970 at age 18 after graduating from John Tyler High School, Hidalgo took a Trailways bus to Detroit, Michigan, to join a Franciscan seminary.

He stayed at the seminary for two and a half years. “A lot of the guys in my cohort that year came out. It was 1970, the first gay pride parades. And we opened our eyes.”

With mounting talk about “ratting out the gays,” Hidalgo said he became fearful and left. “I got afraid and I thought, ‘What if I got kicked out because of that? And then my family hears about it, what will they think?’”

Back in Tyler, Hidalgo worked for the Catholic Church, volunteering for catechism, Sunday school, masses and singing. “I got involved in the charismatic renewal movement of the Catholic church.

For Hidalgo, the turning point away from religion was abrupt and instantaneous at a charismatic renewal conference in Dallas. He attended with his friend.

“The first thing the main speaker said was something [like] ‘People who are criminals and prostitutes and homosexuals…They will never get to heaven.’

“So I looked at [my friend] and I said, ‘Do you believe that?’ She just looked at me and could not answer…

“I had this visual image of taking two crutches and throwing them away, saying, ‘I don’t need the crutch of the mother church anymore.’

Hidalgo looked at his friend and made a life-changing declaration. “I stood up and said, ‘I don’t understand why you hesitated, but I’m leaving now.’ It was a multi-sensory kind of experience.”

Hidalgo said he experienced some positive gains afterward. “In my post-Catholic life, a lot of weights and barriers were released, and I was pretty free spirited.”

Hidalgo discovered some new things about himself. “I have a spiritual nature and I am very interested in people’s religions…I have gained a real wealth of experience,” he said.

After years living out of state and abroad, Hidalgo returned to Tyler, “I tried to find people who are like-minded. But there are also people who I thought would be who are not.”

Hidalgo said he hopes Tyler might become a city with more choices. “I wish for freedom from religion and not freedom of religion. And I just hope that one day it would be a choice.”

Lisa is a retired educator from Hawkins, Texas, now living in Flint.

“I grew up in a cult, the Worldwide Church of God. Really good people, really good morals. It was limiting in ways I didn’t realize,” she said.

Lisa said her sophomore English teacher encouraged her to journal. “It was an outlet to write and to express, to be more me than I was getting to be elsewhere.”

After graduating high school, Lisa attended her church’s affiliated college in Pasadena, California. By her second semester, the school was consolidated to East Texas, so Lisa returned to her hometown.

This time, Lisa wanted something different. “I couldn’t just go back into the bubble. Something broke. I dropped everything, complete clean slate. Left the college, left the church.

“I moved to Tyler and was editor of the college newspaper. I also started acting in theatre…But I didn’t add spirituality,” she said.

It was later, after moving out of state, that Lisa forged a spiritual identity. “I am not a labeler or a joiner or an authoritative type person anymore. I am spiritually eclectic, SBNR (spiritual but not religious).

“My view of God or spirituality really is love. That energy that we all agree to universally, is love. To be a conduit for that is the best that I can do. I want to be that. I have stumbled upon this as my path.”

Matthew is a therapist in his 40s living in Tyler. “I was raised in a Christian background, not too conservative, middle of the ground Protestant. I started to see discrepancies. There are some things you can’t ask, because it makes people feel uncomfortable. I picked up on this at an early age,” he said.

Later, at a faith-based high school, Matthew gained some specific impressions. “It didn’t feel like a right fit for me and I couldn’t make sense of it. That was very much a place emphasizing being a good Christian with a point system, pretending to do it just for social points.

“[There was a] huge emphasis on bringing others into the fold. It felt like a pinball store system,” he said.

As Matthew entered college, his studies created some new inroads. “I took two Buddhism courses that rocked my world. So many things I already thought about were putting words to these ideas.”

As an adult, Matthew continued finding meaning in eastern religions and eastern-inspired ideologies. “‘The Power of Now’ by Eckhart Tolle was huge for me. He drew most heavily on Buddhism. He took principles of attachment and non-attachment and that has always made so much sense to me.

“The real hook for Buddhism in the book was: ‘Question everything; find a better truth.’ I was locked in after that.”

In Matthew’s counseling practice in East Texas, he has noticed a reaction when it comes to mindfulness. “I have learned that in East Texas, [mindfulness] is often associated with bad things. I learned that from clients,” he said.

“In academia, there is so much anti-religion, anti-spirituality. People who deeply believe in science are no different than those they think are totally opposite of them: people who totally rely on faith. I sit in frustration when I hear religion or spirituality belittled,” said Matthew.

“Being in East Texas has been so good for me to learn to talk and listen. I have colleagues with whom I have great conversations. I really like understanding Christians’ worldview.”

Maria Gomez is a 22-year-old psychology student at UT Tyler. Born and raised in Tyler, Gomez grew up Catholic but had permission in her family to become nonreligious.

“We all grew up in Catholic, and we slowly started fading away from that due to family pressures from other relatives and bad experiences,” said Gomez.

Gomez remembers that her dad and siblings drifted away from church together, and had a shared understanding that it was okay to be nonreligious. “We really didn’t really talk about it or have to come out to them saying, ‘I feel like I’m agnostic.’ We just knew.”

Gomez said in high school, she explored her nonreligious identity until she found a fit. “I was seeing that maybe I was atheist, reading over articles and definitions. And then I came across [the term] agnostic. I saw how there’s different types of agnosticism. I found out that’s where I mostly lean towards,” she said.

“I knew I did believe there is something out there, a higher being. But I knew I didn’t feel comfortable following a certain story or a specific type,” said Gomez.

Although Gomez says she notices pervasive signs of faith in Tyler, it hasn’t stopped her from feeling a sense of belonging as a nonreligious person. “I see people’s cars with rosaries, clothing or social media accounts with a Bible verse in their bio, that’s very common.

“It isn’t really problematic to me because I do believe they have their freedom to believe in whatever they like. And it is good they’re expressing it, just as long as they don’t push it towards me or anyone that doesn’t want it,” said Gomez.

As Gomez began studying psychology at UT Tyler, she felt a sense of belonging among her classmates. “They are very open minded of everyone’s beliefs. They also are very curious. They want you to express yourself. All the people there are filled with positivity and want to get to know you,” she said.

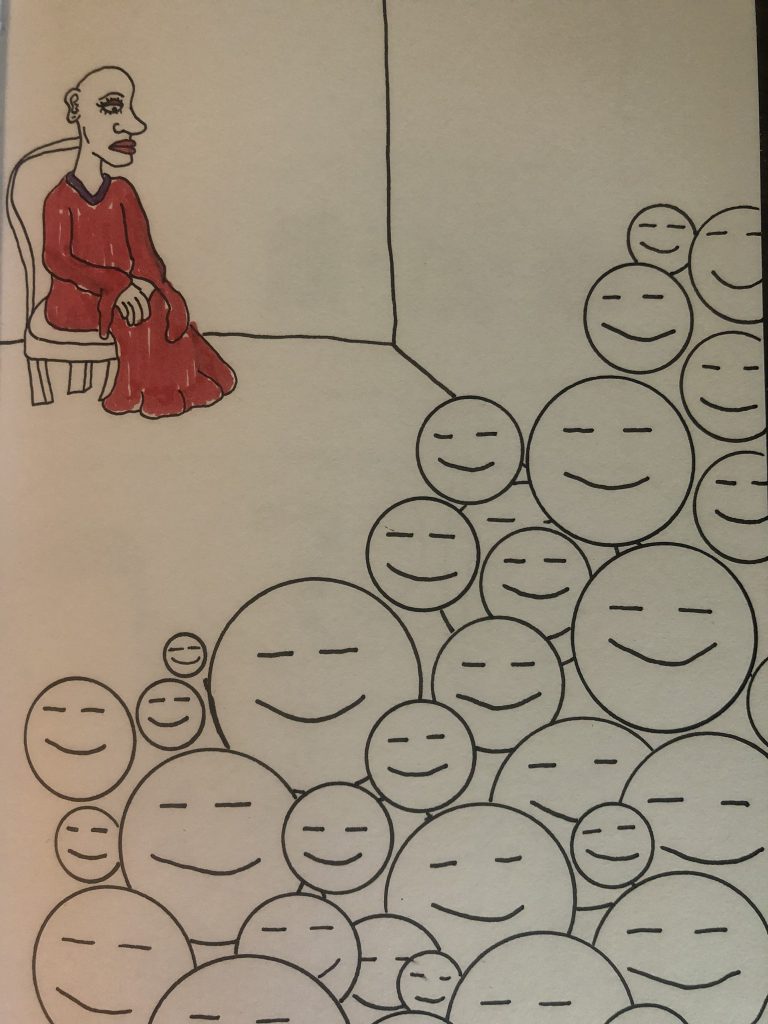

When asked if Gomez would prefer to stay in Tyler after graduation, she said, “I’ve had moments where I feel I should move somewhere else because it is a very close minded place.

“But that kind of defeats the point. If everyone just ends up moving away, then [those who remain] get to stay here. The same beliefs get taught over and over,” she said.

As Gomez commits to staying in East Texas, she hopes religious attitudes sometimes accompanying mental health will change.

“I chose psychology because when people go through really dark times in their life, a lot of people just suggest they go to church, to pray it away or whatever.

“I feel it is very important to actually get the right treatment for mental health problems.”

Kenneth is a 60-year-old physician in Tyler.

Although Kenneth was raised Catholic, he wasn’t interested in it and found religion unattractive. “The deal-breaker to me in religion is certitude. Also the conceit I see in people who think they know. There’s also the violence and radicalism in religion,” he said.

Kenneth said he sees religious thinking as counter to rationality. “I am more attracted to math and analytical thinking. I think people who are religious aren’t thinking like rational human beings.”

Rationality doesn’t keep Kenneth from wanting to feel good about himself. “I want to be a good person,” he said. “I enjoy interacting with people.

“The best feeling is helping a patient. I had a patient who told me, ‘You saved my life.’ A couple of years later, he needed surgery. Afterwards, he said, ‘You have saved my life twice.’ You can’t get more of a high than that.”

As for advertising his lack of faith, Kenneth is indifferent. “It is of no importance to me whatsoever that I announce to people I am not religious.

“I feel no need to tell people about my beliefs and lack of beliefs. It’s not a deal-breaker or a game-changer with who I can get along with. Unless they try to convert me, which is annoying,” he said.

Elizabeth is the co-founder of a humanitarian nonprofit organization and a community advocate. Like the majority of Tyler’s religious population, she was raised in the Southern Baptist Church.

In her growing up years, Elizabeth developed a sense of consequences for resisting aspects of her family’s faith. “There was such definition of what is gospel and any deviation of it is deemed heresy. I knew that to not accept my parent’s beliefs would mean an ousting.”

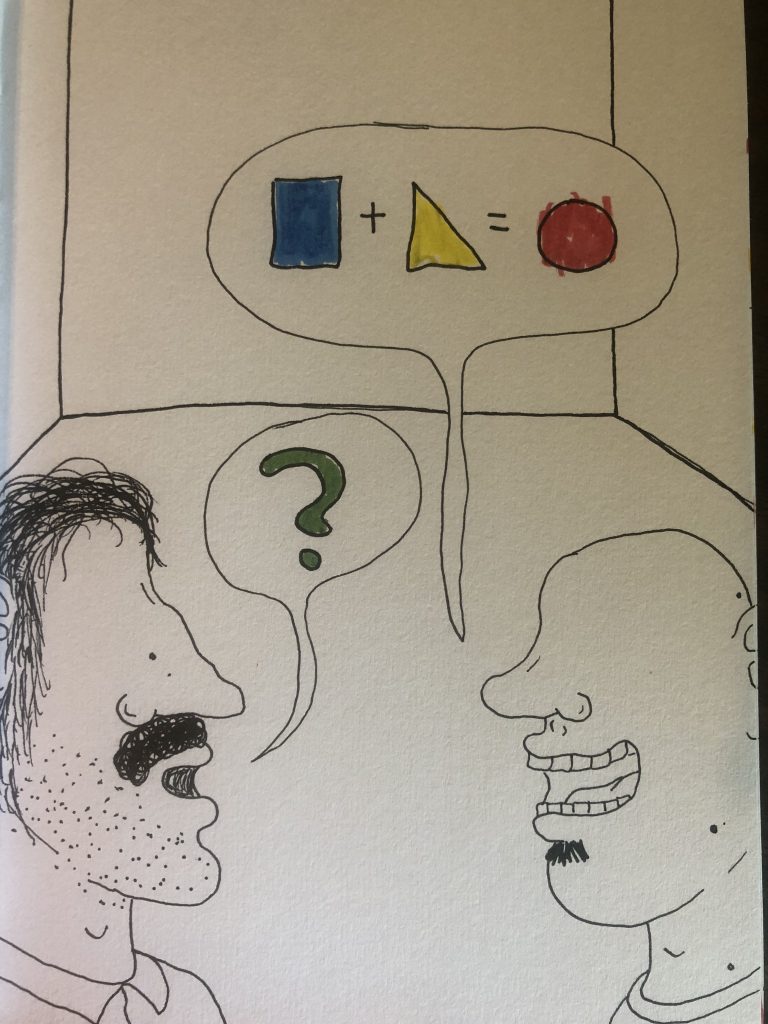

Elizabeth continued to ponder the teachings she received. “One of the things I kept coming across was the centrality of Christ as redeemer. Why is it that Jesus is not enough, but that you have to believe certain points?”

After questioning a particular line of thought in a Bible study she led, Elizabeth was asked to step down. “You buy in and you’re in the flock. But the minute you think on your own…you’re going to die and go to hell,” she said.

As an adult and parent, Elizabeth encountered a family crisis and found herself in a well-known support program. “Strangely, I started dealing with myself. My mentor pushed me to do honest searching and inventory. I knew the cost of being honest about my thoughts.

“I discovered I had totally lost who I was. It created anxiety. To reject what [family and friends] embrace, it’s really difficult. No one loved me; they loved what I was reflecting back to them,” said Elizabeth.

Elizabeth’s shifts from her religious upbringing have made her more aware of Tyler’s deep religiosity and its political impact.

“I did some canvassing for a school board candidate whose push card said, ‘My goal is to bring the church back into the school.’ Twenty-seven people I canvassed, when they learned he was a pastor, they switched and supported him,” she said.

As Elizabeth’s children have grown up in local schools, she notices the presence of evangelical protestant Christian teachings at public events.

“They open and close the school board meetings praying in the name of Jesus, through the blood of Jesus. At football games, [too]. There is very little respect for diversity,” she said.

Joshua “Jammer” Smith is a Tyler native and artist and a graduate of the University of Texas at Tyler. He holds bachelors and masters degrees in English. Smith enjoys coffee and comics, and spends most of his time working on his paintings and drawings. You can follow him here: https://www.jammerjsmith.com

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.