If you’re not one of the 300 people or so people in Tyler and beyond who’ve gotten a chance to ooh and ahh over a vision for downtown Tyler created by Fitzpatrick Architects, here’s what you need to know (and you can see their renderings here).

It’s a grassroots effort to make good on some of the best ideas in Tyler 21, a plan the city put together over a decade ago but remains largely undone. The architects’ ideas are influenced by the principles of New Urbanism, a post-WWII urban-planning movement to make cities friendlier to walkers, not cars, resist racial and economic segregation, and fight what it called “placeless sprawl.”

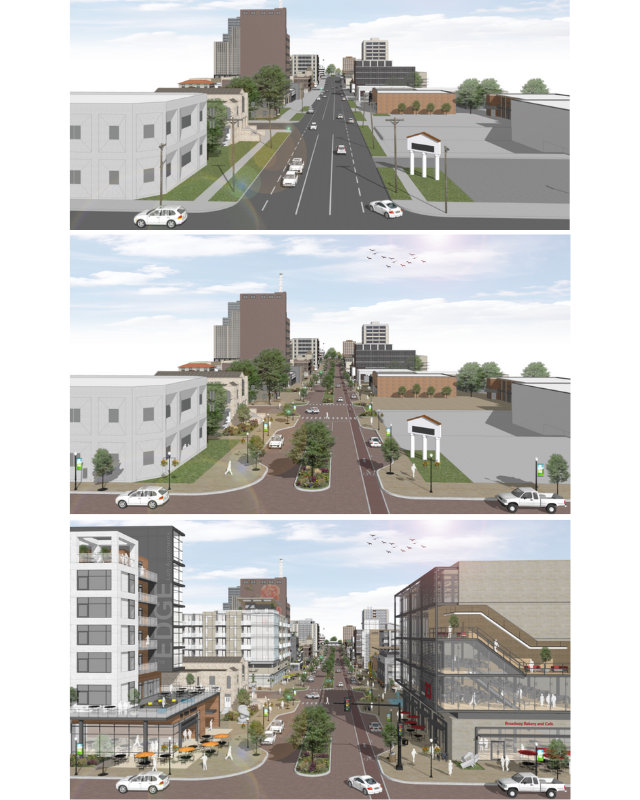

The Fitzpatrick plan—which has earned fans among city planners, elected city and county officials, and downtown developers, along with a glowing writeup in Texas Architect magazine, but has no large-scale financial backing—presents a huge spectrum of possibilities. On one end, there’s a small-scale fix, estimated to cost under $5 million, in which downtown Broadway would get wider sidewalks and fewer lanes. On the far end of possibilities, the plan envisions restitching the square into one large, unified plaza, returning its pre-1955 layout, before the historic Smith County courthouse was razed and downtown was split by Broadway.

I sat down with Brandy Ziegler and Steve Fitzpatrick, the “citizen-architects” behind this vision. As you can see in our updated map of big downtown developments, their firm was behind the design of several renovations that have changed local perceptions of what’s possible downtown over the past few years, including The Foundry, the People’s Petroleum Building, and the current Plaza Tower redo. “When we said we’re going to design a coffee shop there, everybody said, ‘That will never work there. Nobody’s gonna hang out on that corner,'” recalls Steve Fitzpatrick.

The success of The Foundry kickstarted this much-larger downtown vision Fitzpatrick and Ziegler have been evangelizing across Tyler for the past two years. I wanted to know who they hope to serve with this plan, what seems to thrill—or scare—people the most about it, and what they think Tyler stands to lose if downtown doesn’t transform in a big way over the next 20 years. Our conversation has been edited for length, clarity, and order.

What doesn’t work well about Tyler’s downtown today? I’ll get to what does work well, too, but let’s start here.

Brandy Ziegler: There is data showing that consumers spend most of their dollars after 6 p.m. Over 70 percent of consumer retail dollars are spent are in the evening hours. If a downtown is not open in the evening, then it’s not working.

Steve Fitzpatrick: If we had more people living in the downtown area, you’d see people start to spend money in the evening. You’d start to see some of that nightlife. There would be opportunities to create new businesses there—grocery store, pharmacy, cleaners.

Ziegler: Another thing: the pedestrian experience is not there. There’s no connectivity. You want to be able to change people’s mindsets to where they feel like they can park in the garage and then walk [to different places downtown].

Fitzpatrick: What happened is pretty obvious. All the commerce used to be downtown—offices, retail, even entertainment. When I was in high school [in the 1970s], all three movie theaters were on the Square. Everything happened downtown.

In the 50s, Bergfeld Center brought some retail out away from downtown to Azalea District and Old Bullard Road, those nice neighborhoods where people were living. Around that time the Loop came in and allowed people to come around from different directions to South Broadway.

The mall was built when I was just finishing high school.That moved the big retail out of downtown to the mall. That’s when you could start to see the decline in downtown. When people didn’t go down there to shop, it started pulling out. The neighborhoods just kept going further and further south. Office professionals started saying, “Well, I don’t want to drive all the way downtown to go to the office, so I’ll just build my own little office [further south].” The Lowe’s Center changed everything, and that has just kept progressing, with the Grande extension and Loop 49.

What does downtown have going for it right now? What are the assets?

Ziegler: It’s central, and it’s neutral. It’s symbolically the hub that all of us are able to come to—a neutral place that everybody feels comfortable in.

Fitzpatrick: It also has some really great people who are champions, who believe in downtown Tyler and want to see it happen.

Ziegler: It brings this certain kind of person and personality together, people who are willing to step out and say, “It’s a risk, but we’re willing to try.”

Give me an example of that sort of champion for downtown.

Fitzpatrick: A good example is when we [redesigned] the People’s Petroleum Building with Tim Brookshire and his son Garnett. Tim called one day about eight years ago and said, “Hey, can you meet me for breakfast at the Egg and I? I’ve got an idea I want to talk to you about.” He brought up the People’s Building and said, “What do you think that could be?”

It was it was on its third owner, and nothing was happening there. It was like five percent occupied and in really bad shape. I just gave him some ideas based on what I had seen in there.

He said, “Well, you know what, I believe in Tyler and downtown, and the community’s been wonderful to our family for decades. We want to do something that we think will be a difference-maker. We’re thinking about buying that building and converting it and turning it around.”

We put together a plan and an estimate—it was a big investment. They bought it against a lot of other peoples’ advice. But we felt that it had potential. And so they did it, and they did it right, and thoroughly renovated the whole building.

It was a four- or five-year project, and if you go in there today, it’s like a brand-new office building, with all new services, but it still has the genuine nostalgic 1930s feel. We got the restaurant [Jack Ryan’s] and retail on the first floor. It has life. People enjoy going in there now. It worked out perfect, and it’s completely occupied.

In presentations about your ideas for downtown, you mention the bigger Tyler 1st plan put together by the city. For people who don’t know much about that plan, can you explain what Tyler 1st is, and how it relates to your vision?

Ziegler: Cities will bring in experts and have a plan like this done when they’re ready to take on a proactive approach to making their city better. The Tyler 21 plan [as it was originally called] is a big document, and it’s really very good. There are chapters on downtown, on the whole the city at large, on transportation, on parks, and so on.

Did you look closely at that plan when you were formulating yours? Are there examples where you have taken pieces of that plan and folded them into your vision?

Ziegler: We did. We knew if we didn’t, we were isolating that partner [the city]. An example is the Broadway Street Improvement Project [a Fitzpatrick idea that widens sidewalks along Broadway and narrows it from four lanes to one]. We made sure that all the things we were suggesting were also outlined in the Tyler 1st plan. Everything in the city’s downtown chapter and the transportation chapter supported what we were saying.

Fitzpatrick: When we go off onto something completely different is the square. In the city plan, they were doing really simple, low-hanging-fruit things like changing the street lights to be vintage-looking, and naming districts and putting up district street signs.

To us, the bigger problem is that the square is not a square. It’s just a street through downtown that divides everything and encourages a lot of traffic.

We think that it would be better for the square be one continuous piece of land [connecting the current square with the courthouse lot]. Have people drive around it instead. You can’t have high-speed traffic driving through where your pedestrians are, where kids are running around with their families. It’s too dangerous.

Ziegler: Everybody is like, “Well the drive’s gonna be horrible.” No, not necessarily.

Fitzpatrick: Today, if you’re trying to drive to Dallas, you’re not going to be going that way anyway. That’s not what it’s for anymore. We studied other cities, and lots of successful downtowns are doing something like this. It’s not like we’re suggesting something that no one’s ever done.

Let’s talk brass tacks. What does it take to pull something like this off? Whose buy-in do you need that you don’t have right now?

Fitzpatrick: Everybody we talked to about it is in favor of it. Nobody has told us “no.”

But buy-in comes in different flavors.

Ziegler: Right. Buy-in with words is easy.

Fitzpatrick: But money . . . (laughs)

Where does the money come from, and what have you or others attempted so far on that front?

Ziegler: Last year, we worked with the city pro bono and wrote a grant proposal for a federal grant for the Broadway Street Improvement Project. It was denied, but we had a two-hour-long debriefing [with Department of Transportation officials who reviewed the grant] and they gave us excellent feedback, told us we’re close, and said we should definitely resubmit with more data and some other things. We’re ready. The next submittal is July 15.

You’re asking for $5 million, right?

Ziegler: It could be up to $25 million.

Do you feel that landing that grant would potentially unlock other money?

Ziegler: It would, because it’s an 80-20 match. The federal grant is 80 percent. The city has to match 20 percent, and City Council already approved a match. So we’re like, okay. This is our chance.

Fitzpatrick: We thought, if we can get the city to [match federal funds] for the street improvement project, that would motivate the private owners that own those buildings to take advantage of the new streetscape, and do more renovation. So now, they’d be spending private dollars which are going to go towards creating business, creating more taxes, which helps the city. You have this cycle start where the city spent money, and now the private sector spends money, and then the city can spend more money, and all of a sudden you’ve renovated the whole downtown.

The sort of downtown you’re envisioning, can this be a place where mixed-income people can live, work, and shop? Is that important to you?

Ziegler: Absolutely. The whole point is that it’s inclusive.

Fitzpatrick: We’re trying to erase that line [between north and south Tyler].

Ziegler: We want to erase it.

Fitzpatrick: I grew up here, and [that line] has always been there. It’s in the middle of town. We’re trying to make a concentric circle where everybody’s coming into the center and all of the communities around it benefit.

Of course, there’s a complicated thing where, if you make property more valuable, some people may not be able to afford to live there anymore. This is something we’ve discussed a lot.

If people from wherever are buying [single-family homes] and just renting them out, and they don’t take care of the property, is that really the best use of that property? Or would it be better to have somebody buy that home, someone who had a family and wanted to upgrade things, and keep that home in good shape?

Then you could work with a developer and say, “Look, there’s half a block over here that’s empty. What if we built low-income apartments there?” That would serve the needs of people who need that low rent.

Are you optimistic that you’re going to find the potential partners for something like that? Have you had conversations along these lines with developers who are interested in multifamily affordable housing?

Ziegler: I think the city might have to buy into this idea. Right now, there’s not a whole lot of residential housing downtown at all. We’re kind of starting at ground zero. So as we move and build forward, could there be incentives built in, so that if you [a developer] will put some percentage of low-income housing in your development, then you get some amount of tax abatement?

Fitzpatrick: I think we’ll see out-of-town developers come in for the kind of thing you’re talking about. Every place we’ve visited, you see a mixture of all of that. You’ve got to have it all. That’s what makes the downtown rich. I think there’s opportunity for tons of development just north of downtown.

We drive around there all the time and say, “Wow, that’s a great corner,” or, “Whoa, look at that, there’s half a block that’s nothing.” Somebody owns that property, and they have an opportunity to either sell or do something with it.

Let’s just say it’s 20 years from now, and everything in your plan came to fruition. But when you look at who’s spending time downtown, you realize that it’s mostly an upscale white consumer. Is that going to feel like a failure to you?

Ziegler: To me, it would.

Why?

Ziegler: I feel like this is an opportunity for everyone. That’s my belief. [The current divide] is not healthy. We all have something to offer the community, and everybody needs an opportunity to enjoy that. We don’t need this line dividing us. I would feel like it’s a failure if we just flip-flop [between north and south Tyler].

Fitzpatrick: Downtown is the center, and all the communities around it, no matter what color, touch it. If you can bring all of those people into that center, then you’re mixing it up.

Millennial-type people are probably going to be the first ones to jump in and want to live there. They have a different mindset. They don’t necessarily want the half-acre lot with the yard work. They want to live upstairs in the building downtown and walk down to the coffee shop.

I think they’re not also as worried about living in the “right” section of town. You’ll see them naturally mixing it up a lot easier, because they are already comfortable that way.

What is it about your vision that you think is going to result in that mix? What’s going to draw in different kinds of people?

Ziegler: Location is the big one. It’s not 30 minutes away from where people live.

Fitzpatrick: Right, not having to rely on the car. You can be down there and just walk.

Ziegler: We’re really trying to promote transit, and giving people the opportunity to not have to be in their car. It’s a big undertaking, and we will obviously make mistakes, too, because it’s bigger than all of us. But we know doing nothing is the wrong thing.

As you’ve been going around town presenting this vision over the past couple years, what’s one thing that seems to always excite people, and what’s one thing that always freaks people out?

Fitzpatrick: Everybody is always excited when they see what Broadway could look like with new development. Everybody, without fail, is excited about that.

Ziegler: We’ve gotten applause because of the new courthouse, multiple times with different groups. That was unexpected. We thought we were going to get stones thrown at us.

Fitzpatrick: I guess the only negative is it always seems that people say, “You’re going to make the traffic worse.” We say, “Well, you’re not going to take Broadway to get to the square. You’ll come up on Palace or Beckham and come in on some one-way streets.”

Leaving aside the Broadway streetscape, because that’s fairly small-scale, if you could just do one other thing from your plan, what would it be?

Ziegler: The square. We want something monumental there. We want the square to be closed back up. In our plan, we’ve shown a park. It doesn’t have to be exactly what we’re showing, but we want something that brings the community together in some way.

Fitzpatrick: Can I have two things?

Sure.

Fitzpatrick: I would love to see one of those buildings on Broadway, like the Lindsey or Carlton, be developed and be a huge success. We’ve got visions of what both of those could be.

The second thing is, I would want to find a big piece of property—maybe like old Jack King Chevrolet—that was big enough to do an event center, with entertainment two or three nights a week. It doesn’t have to be a city venue. It could be privately owned. It would be another catalyst that would bring people downtown from all directions. You’d need more restaurants, more bars. You need a hotel for people to stay there. It would generate all kinds of activity.

What happens if Tyler doesn’t significantly improve or redefine its downtown over the next 20 years? Let’s say it’s the year 2040, and I’m walking downtown. My fundamental experience, in terms of what I can do, what I can’t do, what I have access to, is the same as it is today. If that happens, what has Tyler missed out on?

Ziegler: When we talk about what other cities our size are already doing—Midland, Lubbock, Loredo, Waco, Georgetown—they are already doing what we’re not doing, with the intention of attracting and retaining talent, and attracting business. It’s already a huge economic hit to Tyler, because we are in competition with the rest of the state.

It’s about the health of the community. When we are not attractive to new and exciting people checking us out to come and put down roots here, our community starts dying.

Fitzpatrick: The net effect would be that you’re going to see more growth and sprawl south, more traffic, and bigger roads. And like the study we’re having to do to figure out what to do with Broadway, you’re going to see more money spent on infrastructure to move cars.

Potentially unattractive and unappealing infrastructure?

Ziegler: Oh, absolutely.

Fitzpatrick: More like Plano. That’s what we’re going to look like.

Ziegler: It sounds like you’re trying to scare people, but it’s the start of the decline.

You’ve also talked about how one reason that you got thinking about the future of downtown was that when you’ve tried recruiting new hires from other cities, they always want to know about living downtown, and you don’t have good answers for them.

Ziegler: Oh, yeah. We are constantly recruiting and we’ve got to retain this talent. People truly are choosing where they want to live by quality of life. There are case studies showing that for many people, a city’s quality of life is defined by, first, their perception of the downtown core, then by educational opportunities, and then recreational opportunities. Those three things, in order, are how people are choosing where they want to go.

Fitzpatrick: It’s competition. We’re going to lack the competitive edge if we don’t do it.

You guys are in kind of a funny position, right? You’re sitting here with all these ideas and all this vision, but you’re not developers. You’re not the ones with the capital.

Ziegler: We have found we’re in a weird spot. We don’t have any money. [Laughs.] Our capital has been earning trust and having good ideas. It’s a movement in architecture across the nation, really, to become more of an advocate for the community. No, you aren’t the developer, but you’re the one that has the design ideas, and you can be the one looking at the bigger picture, and you can earn people’s trust.

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.