Laura Owens is a Tyler parent of five children — three daughters and two sons. Like Laura, her biological children are white. Two of her children, Felix, 14, and Gertrude “Trude,” 16, arrived in the United States from Ghana, West Africa, in 2014.

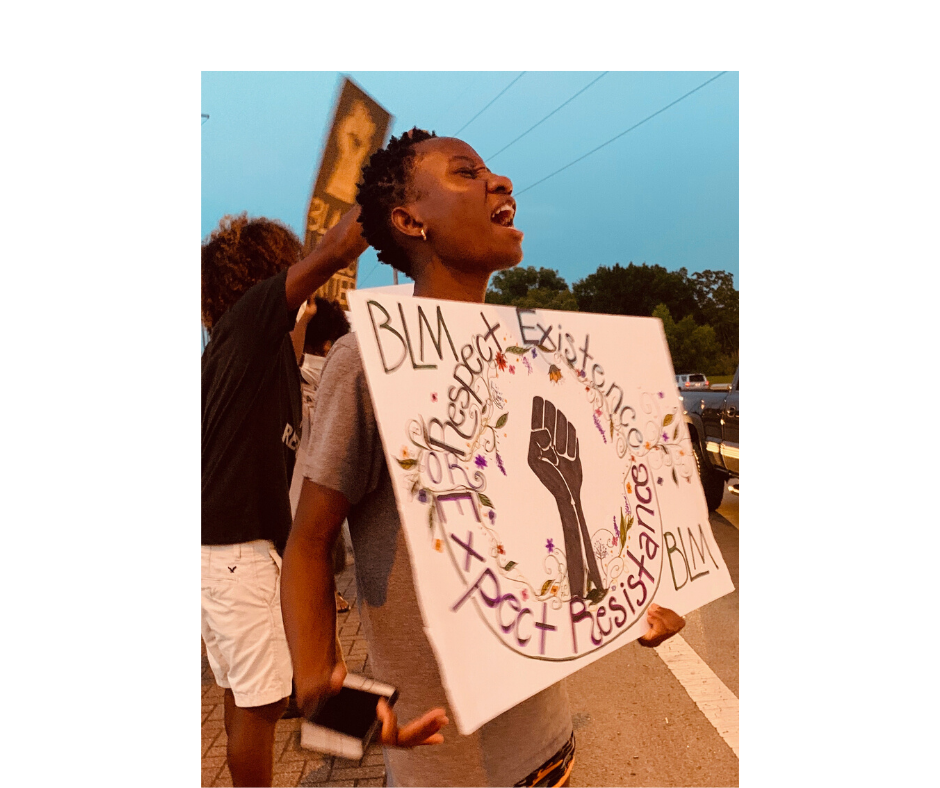

As a parent of Black children, Laura has had an eye-opening, front row seat to racism in Tyler — something she became more aware of as it began affecting her children at school, in stores and on the playground.

Her learning curve has added new books and podcasts to her library, which she shared with The Loop. Here is her story, recounting alarming incidents of explicit and implicit racism, as well as her growing number of tools in response. This story has been edited for length and clarity. All photos courtesy of Lauren Owens.

“I have three biological kids and two adopted from Ghana, West Africa, in 2014. Felix is about 14 years old and Gertrude ‘Trude’ is around 16.

[Before their adoption], I read that children in transracial, adoptive families have incredibly high rates of suicide and depression, especially when being raised by white families. I did my homework. I tried to maintain as much as we could of their culture. I tried to keep their foods, music. But I was very naïve. That was such a small part of what they really needed.

I am white; I grew up in a middle class, privileged family in Mississippi and went to private school. I had heard about it my whole life, but I never personally experienced racism myself. It wasn’t until I adopted Trude and Felix that I truly understood we are still separate and unequal.

As they’ve gotten older, and when I’m not there with them, behaviors are very different towards my Black children. When someone says, ‘Your whiteness can protect you,’ what does that mean? When people see a white mom come into the picture, attitudes and behaviors change, especially in schools. That was happening even at the elementary school level.

One day, I went to pick up my white daughter, Blair. She and Felix were in the same grade, same classroom. I went to pick up, just as I did every day. I asked, ‘Hey, how did Felix do today?’ The substitute said, ‘Well, he was mocking another teacher when we were walking down the hall and getting out of line and dancing.’ Blair spoke up and said, ‘He did not, that teacher’s not telling the truth.’ The substitute teacher looked confused. She thought I was the daycare worker picking up kids. I said, ‘I’m his mom.’ And her attitude just flipped very quickly.

One of the most grotesque [racist incidents] was at the Scholastic Book Fair. An older white gentleman came up to Felix, handed him a book. And then the man chuckles and leaves the library; he leaves the school. And we said, ‘Felix, what is that? What did he say?’ [Felix said], ‘He told me I’ll need this one day when I get older.’ We read the title, and it was something like “The 20 Scariest Prisons in the United States.”

We immediately alerted the principal. The school solution — instead of addressing the overt racism — was, ‘Well, this isn’t an appropriate book for an elementary school book fair. We’re going to have the book removed.’

In another instance, we were at the ROC playground in South Tyler. I was sitting within earshot, and some kids said, ‘We don’t play with kids who are Black.” My other kids jumped right in and said, ‘We don’t play with racists.’ The other parents could hear this, too. These kids were in middle school and high school. That is what’s scary to me.

During the 2016 presidential election, my children were both told to ‘go back to where they came from.’ Luckily, every time, they’ve had a white sibling with them. Anytime we go anywhere, their older, white siblings follow them because of the things they’ve experienced.

I started doing a lot more research and asking uncomfortable questions. As a mom, I need to protect my children.

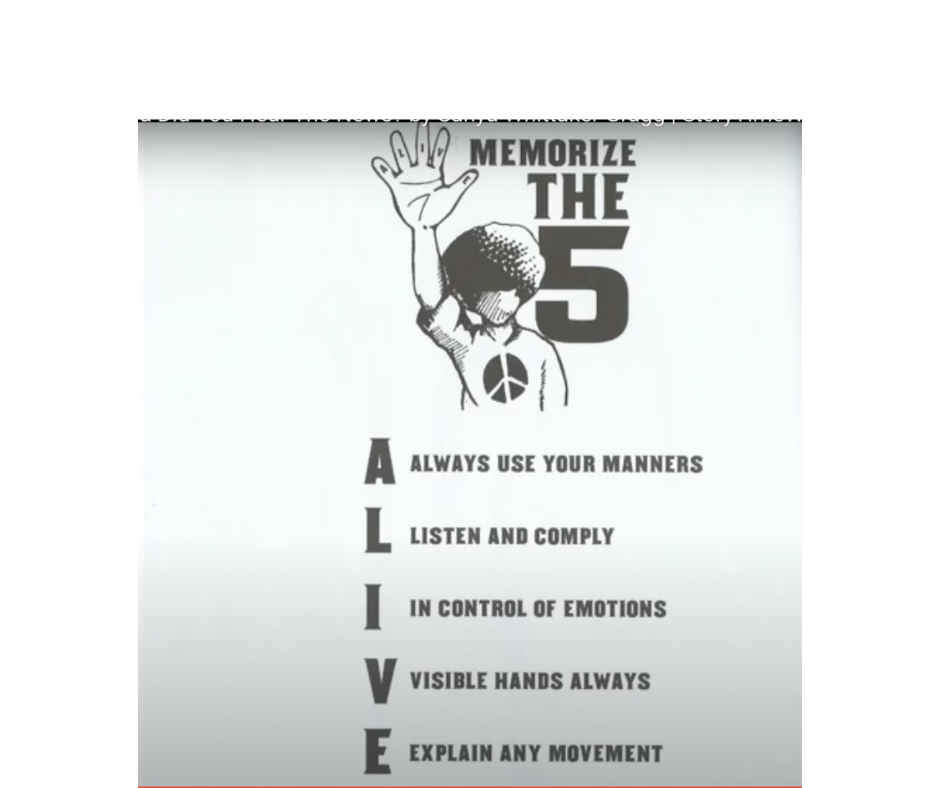

We have rules: ‘You can’t wear a hoodie in the store.’ ‘Have your hands out of your pockets.’ ‘When you get stopped by a police officer or store security, you say, ‘My name is Felix Lamb. My mom is Laura. Her number is this.’ Especially with Black boys, the research tells us over and over they look much older and are considered a threat.

One of the earliest things [I learned] was you’ve got to have the talk. Most of us white people think of the sex talk. No, that’s not it. There’s a juvenile book called “Mama, Did You Hear The News?” It has a great page in the back with some steps about what to do when you get stopped.

We have a couple of points taped to the car dashboard to remind them: have your hands always visible, talk in a very non-threatening tone, say, ‘I do not have any weapons. My driver’s license is in my pocket.’ I’ve never had to do that with my white children.

One time, walking home after school, Felix forgot his key, so he climbed over the fence. I said, ‘You can never, ever, ever do that.’ [He protested,] ‘Mom, I forgot my key.’ ‘You can never, ever do that. Someone might think you’re trying to break into our house. You have to just call me and sit outside and wait.’ And that afternoon was like 100 degrees.

Kids have been killed going into their own houses. It happens in whiter neighborhoods. Black kids have been caught crawling in windows in their own homes, and someone calls the cops on them. His white siblings, they jump the fence all the time. There is definitely a different set of rules for them, which is hard, very hard, parenting wise.

Then, there were the comments. ‘You won’t have to worry about them because they’re being raised by white people. They’re not going to be like Black people. Your kids are different.’ I would hear that explicitly from people that I’ve sat next to for years in church. I’m not friends with them now.

I don’t like it, but that shows me someone’s overt racism. I know who to protect my children from. You say something like that, you are cut — no part of my life, my children’s lives either.

Felix started sixth grade at Hubbard. At his parent-teacher conference, the principal, Jeff Sherman, says to him, ‘You’re doing great,’ just really charging him up.

Then the assistant principal says [to Felix], “You need to look at people in the face when you are talking to them. That is very disrespectful.’ Wow. I said, ‘I’m going to stop you right there, ma’am. Where this child came from, if he looked you in the face when he talked to you, he would have been beaten. He doesn’t look you in the face because he has very little schema for having conversations with adults. He is doing what he’s supposed to do socially and academically.’

[She replied,] ‘Oh, I’m going to London at Christmas, and I’m worried that I might do something wrong there.’ [And I’m thinking,] ‘Not today, Karen. Not today.’

It’s very alarming, our school districts are doing no training for implicit bias. Implicit biases, we need to discover what those are. We all have them. Counselors are less likely to offer college advice to nonwhite students. Nonwhite students have less people in their families who have navigated the college system. How many of our counselors are reading these studies and going in and asking these communities?

[Trude’s experience] has been very different from Felix. She is very introverted; I think that plays in her favor some. Thankfully, at her school, Robert E. Lee, she has had some amazing Black and Latinx women role models who have been a lifeline for her. She also has her running community that has been very affirming.

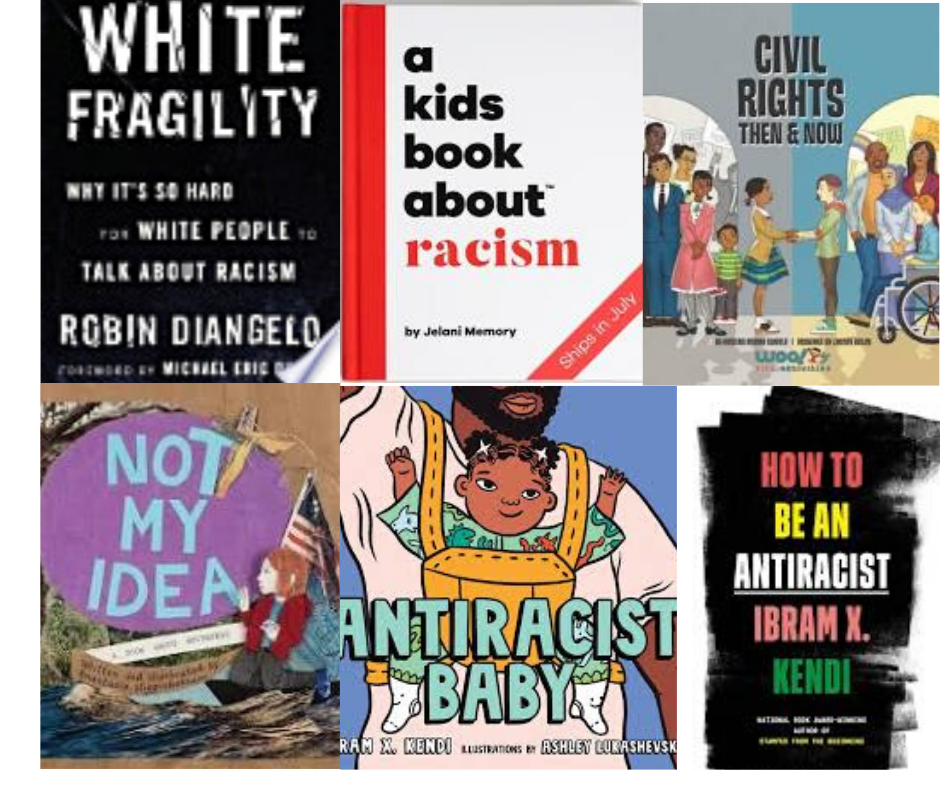

My advice [for my white friends] is to tell your young, white children what racism is, what it looks like. There’s a difference between being inclusive and affirming. An inclusive family might watch TV shows or have books that have different colored people in them. Affirming shows and books highlight the racism and the inequities in our community. That’s very important for parents to do.

When people hear the word white privilege, they turn off. ‘I can’t help it that I’m white.’ Okay. Don’t let labels turn you off, and listen. Listen to people’s stories. If you’ve never had positive experiences with Black people, find a way to do that. Even if it’s just something as simple as listening to a podcast, reading a book, joining a Facebook group. You might join and just be a listener in it. Don’t speak in it; don’t write things. Just listen. Don’t feel like you have to always be on the defense. I like the book “White Fragility.” It’s a hard read. Read it. Let’s talk about it.

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.