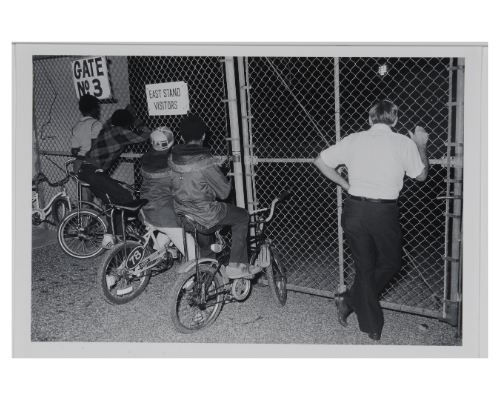

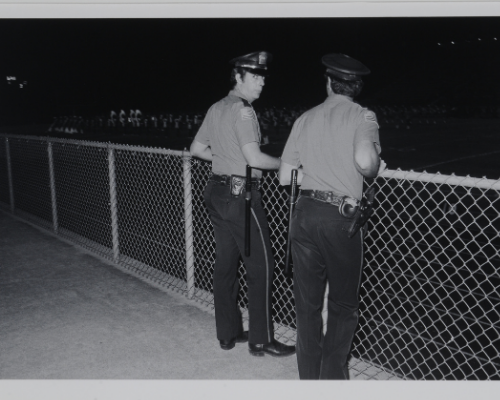

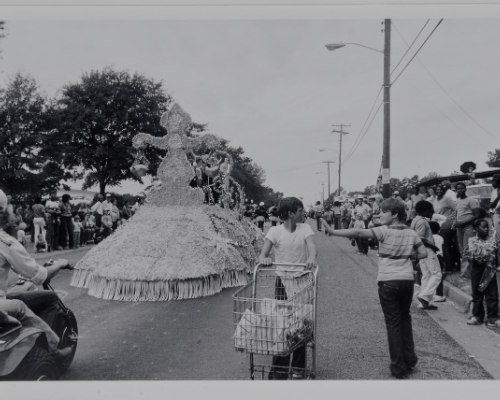

Editor’s note: Phil Latham’s story, below, is paired with untitled photos by Judy Bankhead’s My Town, which documents Tyler in silver gelatin prints from 1979-1981. Bankhead’s lens captures a bygone-yet-recognizable Tyler, and The Tyler Loop is thankful for her contribution. Special thanks to Leah Scott and the Tyler Museum of Art collection for helping make Bankhead’s photos available. Here, they serve as a visual complement to the 1970s Tyler portrayed in Latham’s story.

The 1970s had just begun in Tyler. It was a time when a “service” station meant that someone else pumped the gas and washed your windows while you waited in the car. Gas was less than 50 cents a gallon.

Casey Scurlock was not long out of high school, working at his grandfather’s service station to pick up some extra money while attending Tyler Junior College. His co-worker, Al McCoy, was older. For Al, the job was one of several he held to trying to keep his family afloat.

Scurlock is white; McCoy, who died in 2019, was Black.

Between checking oil levels and adding air to tires, McCoy and Scurlock talked in a way few people did at the time: They talked to each other. Perhaps, more importantly, they listened to one another.

“Al and I had time together to talk and for some reason, he allowed me into a corner of his world,” Scurlock said. I had met or known many Black men who had worked with me or at my grandfather’s gas station. All of them were good people working to support their families. I met Al at one of those jobs. He was working three to four different jobs to make ends meet.”

While McCoy concentrated on earning a living, much of Scurlock’s energies were focused on getting through TJC. He desperately needed a good topic on which to write an essay. Thanks to his conversations with McCoy, Scurlock chose to write about his newly formed discoveries about racism.

“That started me down a path that opened my eyes to how we treated African-Americans in East Texas,” he said.

But it went further than words on paper. McCoy and Scurlock decided to become much more active, wanting to do something positive. They decided to form a new organization dedicated to improving communication between white and Black Tylerites, as well as the treatment of Black residents.

They were about to learn the difficulty of such a task.

Dragging Tyler into integration

The idea of forming a group was particularly timely because of school desegregation. The Tyler ISD school board was in the throes of trying to figure out school integration — or, rather, look for some way to avoid or delay it.

The Justice Department had ordered the Tyler school district to integrate in 1965 and the district responded by choosing to move toward that goal one school grade per year. Six years later, in 1971, the district was just 20 percent integrated. The biggest leap would come when the junior high and high schools were integrated.

The Tyler Morning Telegraph reported considerable dissatisfaction among the white population in letters to the editor and elected officials quoted in news articles.

A group that called itself Freedom, Inc., regularly published ads in the paper, including one on August 16, 1970, which said their rights, “and our children’s rights,” were violated by the desegregation orders

On August 30, 1970, The Tyler Courier-Times reported concern that there would be a demonstration by residents to prevent desegregation. A “public speaker” had urged parents to take their children to the nearest school and stay with them all day. The paper warned, however, that doing so would be against the law, disrupting classes.

Federal Judge William Wayne Justice ruled in a series of lawsuits that Tyler’s movement was too slow. The district would have to immediately integrate in the coming year. The ruling roiled the community and led to appeals of Justice’s decision all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Tyler ISD lost each attempt. To add salt to the wound, Justice ordered a bi-racial committee to be formed to help the integration process. The committee would report to Justice on the school district’s progress.

People Who Love People

In this atmosphere, both Scurlock and McCoy saw an opportunity to help make matters easier for the community.

Plus, there were other matters that needed attention, including alleged harassment of Blacks by law enforcement officers. Another was the fact that the Tyler newspaper refused to print the wedding announcements for Black couples getting married.

McCoy and Scurlock formed “People Who Love People,” an organization meant to help ease integration in schools and work against the segregation that was so prevalent in Tyler.

Neither man was a player in community politics, but both had many friends. The idea was for McCoy to reach out to the Black community and Scurlock to contact white residents who might be interested.

Scurlock found genuine interest from Tyler’s Unitarian Universalist Fellowhip and the fledging chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Among those engaged community members was Jacqueline Daves, who remembers moving to Tyler in 1963 and seeing the remarkable extent to which segregation was enforced.

“Everything was ‘white’ and ‘colored.’ It was wild,” she said, noting that stores even sold wedding rings for white and Black couples. She and then-husband Don Zeiger heard Scurlock’s idea at the Unitarian Church and did not hesitate to join.

“There were a lot of problems in Tyler then,” she said. “I know there was a problem with real estate. Back then, an agent wouldn’t even show Blacks a house in South Tyler. That wasn’t where Blacks were supposed to live. Then there was the educational system. The sense was that North Tyler was getting the leftovers from South Tyler.”

After Scurlock mined the Unitarian congregation, he decided to look for more traditional sources. He was sure that those who were the bedrock of the community would want to improve race relations.

That’s when he would get a dose of the reality.

“The old money families were almost violently opposed,” Scurlock said. “They stated clearly that they expected a violent rebellion by the Black citizens.”

Daves said her Black Tyler neighbors were much more open to the idea of working with whites to end segregation.

“I know Al was able to get quite a group of Blacks interested in the idea, but there wasn’t much acceptance in the white community.”

As a result, Scurlock said, the first meetings were sparsely attended with cautious, noncommittal participation.

“This was always by older women with only a few men. Then people began to open up a bit. Before I had to leave, I was cautiously accepted as someone who cared.”

Scurlock’s time was cut short when he was “goofing around” with McCoy and made a “kicking move” at something McCoy said.

“I offended his wife and others,” Scurlock said. “It took her months to tell me that I had symbolically humiliated him. It took me a long time to begin to understand. It was never the same and I only saw Al a few more times.”

Later years

McCoy stayed on, however, as did Daves and others until at least 1973, though it is not clear when the organization disbanded.

The group was scheduled to meet twice a month at St. John’s Episcopal Church and held candidate forums for some elections.

In what may have been the group’s largest public success, People Who Love People held “Happy Day” in 1972, which brought people from all races together in a celebration. The event, held in April at the Rose Garden building on the East Texas fairgrounds, aimed to celebrate gains made in racial relations in Tyler. The newspaper reporter covering the event for the Tyler Morning Telegraph noted that, “little was said from the bandstand or among persons in the audience about” racial prejudice.

Daves recalls some of what the group was able to accomplish, including nudging the Tyler newspaper to publish photographs of Black brides.

“I used to say that Tyler had a “Rose Garden mentality,” that there were no problems, no crimes, no racial problems. I hope it has improved.”

In some ways she has seen some positive changes, such as the common sight of mixed-race couples in public, an act that was almost unheard of when People Who Love People was formed.

Daves’ daughter, who went to Robert E. Lee High School, told her she is horrified at the racist comments made by her former high school classmates in a Facebook group, in response to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Her daughter’s friends are also incensed, she said, over school name changes and the possibility of statues being removed.

Daves, who in 1971 was selected by U.S. District Judge Justice to serve on the bi-racial committee to help with integration in Tyler ISD schools, does not know much about what happened with People Who Love People after 1973.

That year, her 16-year-old daughter was killed in an accident and her attention was naturally focused elsewhere.

What has stayed with Daves was the way the Black women came to her aid after that tragedy.

“All those women came over as a group one day and cleaned my house and cooked,” she said. “It was the most wonderful thing.”

Phil Latham has been an East Texas journalist for more than 45 years as a reporter, editor, publisher and editorial page editor. He writes a weekly column available at https://platham56.wixsite.com/website. He has also written two novels. Readers can contact Phil at [email protected]. He lives in Smith County with his wife and three pups.

Judy Bankhead lived in Tyler until she graduated from high school in 1969. She completed a Bachelor of Fine Art degree in Photography in 1973 and a Master of Fine Arts from Rhode Island School of Design in 1976. Her collection, My Town, commissioned for The Tyler Museum of Art, asks us to “reconsider what we often take for granted or ignore, tell(ing) us things that we may, or may not, want to know.”

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.