North Tyler native Bishop David Houston remembers “The Cut” and its heyday in the 1950s and 60s, when Black-owned businesses were concentrated along Vance Street and Palace Avenue.

The businesses sprung up in the early 1900s as a product of Tyler’s segregation policies, relegating Black residents to live and own businesses separately from white residents. For a more thorough treatment of the history of segregated housing in Tyler, see The Loop’s story by Luke Lee.

Bishop Houston says the business hub became more than a place for shopping and dining. “The Cut” became a neighborhood center, where residents from multiple generations could visit and catch up.

“The Cut” dissolved in the 1970s, as desegregation slowly moved clients into the central and south parts of Tyler that were formerly banned or unwelcoming to Black residents.

What might it take for “The Cut” to see revitalization today? Bishop Houston weighs in, as well as CBS-19’s 2019 video, “The Cut: The town Tyler forgot.”

Here is Bishop Houston’s story in his own words, edited for length and clarity.

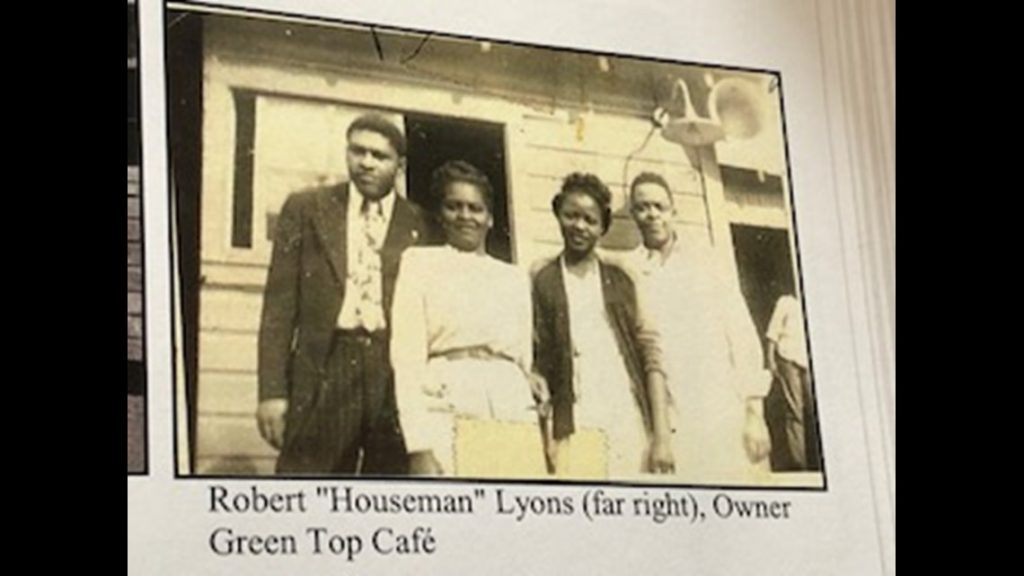

“Well, I was born and grew up about four blocks from the place we call “The Cut.” It was kind of like a shopping center. Most of the Black businesses were at that particular location. As far back as I can remember, those businesses had always been there.

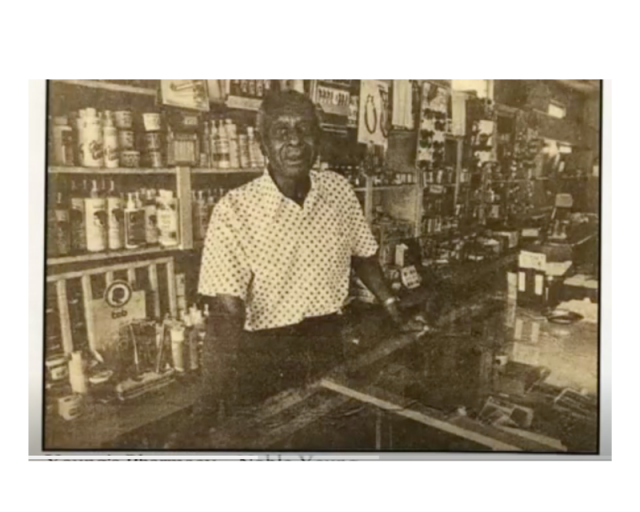

You had a pharmacy, you had restaurants, you had hotels, service stations, gas stations. You had movie theaters, barber shops, beauty shops. You had shoe repair there; cleaners and certainly grocery stores there, as well.

So it was kind of like a meeting place and shopping center, kind of where people gathered — churches there, as well. You know, all that was there. It was the place. All of us gathered; it was a place for socialization, where you’d meet down there and discuss all the problems and solve the problems of the world.

You had senior citizens there as well as the young people; school kids. The bus stops were there. After activities at the school, they’d gather there and discuss whatever happened.

There was T.J. Austin Elementary School, Emmett J. Scott Junior High and Senior High School as well. That was McDowell’s Kindergarten, there was Mrs. Mary Luin’s Kindergarten at that same general area.

The term we use is integration, but there was never integration. It was desegregation. We never had an integration really. With desegregation, all of those options were open, and people went there. And consequently, many of the Black owned businesses just got out and ownership died out, too.

And the young people didn’t take it up, so it just kind of faded. For the most part these businesses didn’t move, they just closed, died down primarily because there was not any place for them to move.

You had businesses in downtown Tyler, a place we call Wall Street, which was East Erwin on Spring Street down a couple of blocks on East Erwin. It was a location for many Black owned businesses downtown. Each section of town had its own business section, like the white city area, the east end area — they had their own businesses.

There wasn’t any place for (“The Cut” business owners) to go. They didn’t have places they could move to. All the other businesses were in different areas, eventually moving south and everywhere else. A few may have survived and gone to other places, different locations. But they were newer businesses, not the old original businesses on “The Cut.”

During the 60s to 70s [The Cut began to dissolve]. And you know, then Emmett Scott closed. Texas College was fortunate to actually survive.

It is still functioning, it’s viable and the North Tyler area as well. But that was the situation per se.

We have a lack of grocery stores, you know, and the mom and pop grocery store was at a difficult time trying to compete with the majors chains. The Safeway moved in. Brookshire’s. Lassiter’s. Piggly Wiggly. People just started migrating there, doing business there.

And the smaller, mom and pop kind of corner grocery stores just faded away, went out of business.

In those days during segregation, we didn’t have any options. You had to go to the Black businesses because white owned businesses were in different locations and you weren’t treated with respect in those places.

We were proud people. You know, we had our own everything in the community. We didn’t have to go out of the community for anything.

And we didn’t realize what we really had until we lost it.

We lost all of our businesses. We lost a lot of important people connected with them and services and so forth.

And most of all, we lost our children, our most important product.

We had a community and everybody kind of looked out for each other, knew each other. Senior citizens would keep the young people in line. They had respect for them. We’ve lost that sense of community since that time, unfortunately. But these are symptoms of the time.

You see, we had in Tyler The Palace Theater, which was downtown on North Spring Street, where Regions Bank is located. That was a Black movie theater.

Later on, we had two theaters out on The Cut and North Tyler. We had the Karamu and the Harlem Theater there on The Cut. We didn’t have any other options. When the other things developed and other options took place, these businesses went out because of lack of support.

A terrible loss, perhaps never to be regained again.

We still own property in North Tyler, my homeplace in North Tyer. My brother is still there and other relatives in North Tyler. And our church my father started in 1930 named for him, Houston Temple Church of God in Christ on the corner of Nutbush and North Palace. It’s still thriving.

We have opened up the Ceaugry and W.B. Houston Senior Center there on Cochran and North Palace. It’s a multipurpose center that our family, the Houston family, built and operates in North Tyler. We did this because North Tyler is where we we were born, where we grew up with the church, went to school — and we’re just trying to put something back in the community for community use.

People may not even know that much about it. It’s been existing for over five years. Our family built it, better than a million and a half dollars. We feed people out of there, we having clothing. We have community meetings for community action, we have health fairs and everything. We’re proud of that.

[The Cut area] used to be predominantly Black, but the demographics have changed. It can be [developed], but it’s got to be a joint effort now. Not only just Black people, but all the others who are involved there. They’ve got to work together.

And the city has to do its part enforcing certain city ordinances already on the book [instead of] not concerned about codes. And so they’ve got to work together to bring it back.

At our center, we have signs up for over five years: “We are revitalizing North Tyler. Join us.” Out of that center, we have community development, community empowerment, a meeting place, jurisdictional headquarters right there.

We are acquiring other properties that we can to try to keep the community viable and keep some sense of beauty and decency there. In North Tyler, you got a whole lot of absentee landlords and things like that. We had a time when we had homeowners where people took pride in their homes.

Now these places have been lost and abandoned.

[To revitalize North Tyler], it would take individual land owners and business minded entrepreneurs to come back and establish necessary businesses in the community without fear.

See, what happened in desegregation, it went one way. Black people started going to white establishments, but white people didn’t come to Black establishments. People seem to be afraid to come to North Tyler because of what they think. It would appear to be the situation there.

The city has just got to stop letting anything happen there: people building anything they want to. Isn’t there a city code that says you can’t park in your yard? You gotta be on the pavement, driveway or something like that?

I seem to recall that as being a city ordinance, but that’s not enforced in North Tyler. Dilapidated, abandoned properties.

People have got to cooperate. The city, the homeowners.

I would love to to think that North Tyler development would go back into the community for community development. But, you know, it’s going to take a whole lot of collaborative effort to do that.

I’ve been in Tyler all my life. I’m proud of the city, the growth of the city, all that has taken place. But if it’s going to be a unified city, all parts of the city need to be included.

Tyler seems to be doing a little cosmetic stuff, putting in sidewalks and curbs and things like that.

That’s something, but something more needs to be done.

There’s room for expansion, you know. Tyler has gone just about as far as they can go south. We got plenty of good room on the north part of town, if the city keeps its promises and plans that may still be on the book.

I want to see that this part of town receives the same kind of treatment, recognition and the care of other parts of the city.

They don’t get slack on the taxes. We still pay taxes in North Tyler, so why not treat it like a regular part of the city?

I would like to see it. I may not ever see it in my lifetime, but I’d like to see it developed.

We are proud of the Houston Center. I just wish other things would follow suite. We hoped that by doing so that others would do something, too — take interest and be inspired to do something.

We don’t have a major grocery store in the North Tyler area. We don’t have really a pharmacy, a drug store. And we don’t have really a North Tyler restaurant. We had one, it closed.

The people have to go out of the community all the time for most anything.

I would like to say that North Tyler is a part of Tyler. And treat North Tyler like you would treat any other part of the city. Don’t abandon North Tyler and say, “Nothing good could happen there.”

If anybody needs financing for something, then you need to take the chance and do it. Don’t just say that because it’s in North Tyler, “Thumbs down, no hope.” We ask for nothing special.

Treat us like everybody else. Treat North Tyler with respect, with the same consideration you would treat any other part of the city.”

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.