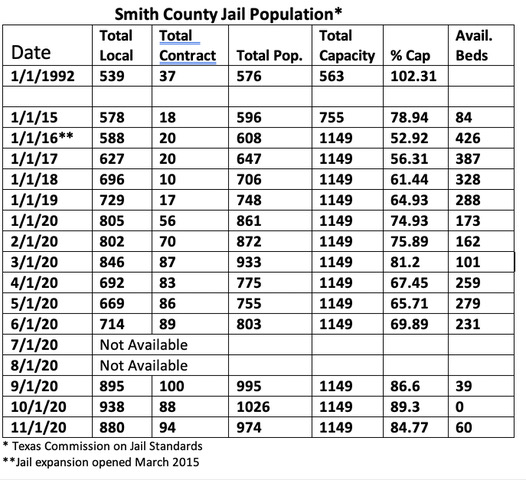

The increasing Smith County Jail population has been a concern of mine for years, along with county officials and residents, both before and after voters passed an approximate $33 million-dollar jail expansion project in 2011. I began researching for this story with jail population in mind.

Prior to the expansion, jail capacity was 755 inmates. After expansion completed in 2015, jail capacity increased to 1,149. Instead of allowing room to spare, the jail population has continued a steady increase, as evidenced in jail population reports from the Texas Commission on Jail Standards.

Smith County Jail is once again at capacity, necessitating some inmates being housed — at an added cost to the county — in other county jails.

Given this continued increase, I took a closer look into just how our jail is populated. And I wanted to know more: What are the impacts of COVID? What are arrest and bail-setting procedures and types of charges? What are the ways to get out of jail, barring full disposition of a case? And just who, offense-wise, populates our jail?

Smith Co. Jail responds to COVID

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on the jail population, pushing the numbers higher. County officials have taken some steps to decrease that number. According to Smith Co. District Attorney Jacob Putman, there were attempts to relieve jail population during the early days of the COVID.

Smith County, along with Tyler and Lindale police, began using an option in the criminal code that allows cite and release for certain Class A and B misdemeanors.

According to Putman, “For a class C you pay the fine and never have to go to court. For a class B or A, you have to go to court at some point, and typically that is through an arrest. Using the cite and release option, instead of being arrested, you are given a summons to appear in court on a certain date and time.”

Sheriff Larry Smith said his office was “looking at going full time” with the cite and release option. However, after a couple of months, it was discontinued. Both Putman and Smith say they are no longer doing cite and release. Putman said this is because the “court appearance rate was about 50% or less.”

According to Smith, “We had to get non-violent inmates out to get some relief, because our population was exploding. We needed the beds for felonies and more violent crimes because TDC (Texas Department of Corrections) stopped taking inmates. We had to take inmates out to Gregg County and San Jacinto County.”

Smith, working with the county court at law and district judges, secured release on personal recognizance (PR ) bond — no money bail required — for 95 to 100 inmates being held pre-trial on non-violent misdemeanor or low level felony offenses.

Putman concurs with Smith. “If anybody could be released, these would be the least risk to the community.” There is no data as to whether those releases are appearing for assigned court dates.

“I don’t believe the courts are having external docket calls — hearings for those out on bond as opposed to those detained in jail — right now because of COVID. I assume that those released are checking in with probation as that was part of the bond agreement,” said Smith.

The decrease in the jail population through April, May and June 2020 can be attributed directly to these measures taken in response to the threat of COVID among the rising jail population.

Drivers behind increased jail population

Pandemic and relief measures aside, the jail population has continued to see a month after month, year over year increase. In a recent interview, Sheriff Smith shared what he perceives as the primary drivers of the increase.

“I think it is several different things. One is that you have a lot of people who are unable to make bail or secure a bail bond. From that same perspective, there are those previous offenders out on bond who get arrested again and get a higher bond, so they are unable to make it and get out.

Part of it is just more concentrated law enforcement. We have a lot of crime, and we have a lot of people arrested.

I think the main driving force is the felony offenders who stay in jail for a longer time awaiting appearance in state district court. I believe we are in dire need of an additional district court here in Smith County.

The figures show that we are eligible to get one, and I have talked to our state senator and several representatives about this upcoming legislative session and getting another state district court.

When COVID came about, we immediately kicked off the Zoom court for those already incarcerated, and we had a lot of them. I think our pre-trial felonies were running around 400. We are up to 500-plus now.

But we got down to less than 200 [because] we were not having jury trials, which allowed the courts to concentrate on the cases incarcerated, and a number of them were guaranteed probation just because of the offense committed.

When jury trials are ongoing, the court doesn’t have time to get these cases through the docket. When the courts were able to focus on just the inmates because of no external trials, that allowed them to get a lot of cases taken care of and inmates moved out of jail. Again, this shows the need for another district court.”

Higher incarceration rates

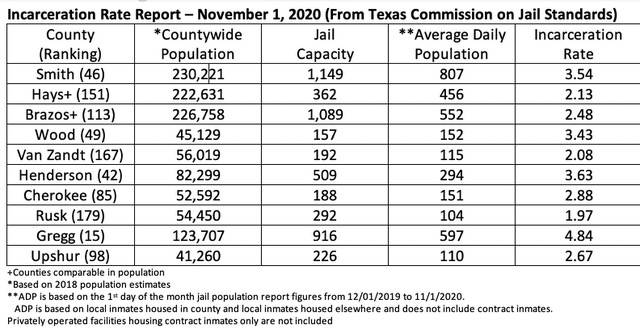

The incarceration rate — the number of inmates in custody relative to the population — for Smith Co. is 3.54. It ranks 46th of Texas’ 254 counties.

Smith attributes Smith Co.’s higher incarceration rate to the “very conservative law enforcement in Smith Co. and all its incorporated entities: Arp, Lindale, Whitehouse, etc. Plus, Smith Co. has very good prosecution. Also, people like to come into Smith Co. and commit crimes such as the vehicle burglaries that we have going on right now.”

The Smith Co. incarceration rate is higher than Hays County at 2.13 and Brazos County at 2.48, both of which are comparable to Smith County in population, and all are counties with colleges and universities.

Smith believes Hays and Brazos counties rates are lower because the counties “are too close to Travis County and have a higher tolerance for certain offenses because of the universities, I would guess.”

With that, we might surmise that incarceration rates are impacted by the geopolitical nature of the two areas — East Texas versus Central Texas.

Smith County and all of its adjacent counties, with the exception of Van Zandt and Rusk, are ranked in the top 100 counties per incarceration rates. Gregg and Henderson counties’ rates are even higher than Smith Co., creating a pocket of high incarceration in East Texas.

Go to jail: Arrest

Contrary to Monopoly fun and games, the “Go to jail!” sentence is no laughing matter.

According to Putman, “Most arrests are either an onsite arrest or arrest by a warrant. Most people are familiar with an onsite arrest. A common example would be a DWI (Driving While Intoxicated) charge. An individual gets pulled over, and the officer determines the person is intoxicated. The individual is arrested on the scene and taken to jail.

The law in Texas requires that a magistrate judge — in Smith Co. that would be a Justice of the Peace — meet with the accused within 24 hours of the arrest and inform them of their rights. They have been charged with a crime and they have a right to a lawyer, etc. The JP will set and inform them of their bail.

The other type of arrest is by warrant. This occurs when an officer, usually a detective, investigates a case — a robbery or murder for example, that didn’t happen in front of him.

The detective investigates to figure out a likely suspect. When determined, the detective will have a judge — county court at law or district — to sign the arrest warrant.

Typically, when the judges sign the arrest warrant, they will include the amount of bail on the warrant. The DA’s office is not a part of the arrest and bail process.“

Magistration, arraignment and Miranda

Smith Co. Precinct 3 Justice of the Peace James Meredith recently explained the JP’s role as a magistrate.

“There are five of us JP’s on rotating call to serve at the county jail. When I am on call, I go to the jail every morning to magistrate anyone who has been arrested in the last 24 hours.

There may be three people; there may be 23. First thing I do is get all the accused together, introduce myself, advise them as to what we are doing, read them their Miranda rights and make sure they understand them.

I then look at the affidavits and other paperwork for each accused to determine what the arrest was for and whether there is probable cause for the arrest.

If there is probable cause, I will sign off on the arrest. I then speak with each accused individually and advise them of what they have been charged with and set their bail. If the arrest was by a warrant, typically the bail has been set already by the court of jurisdiction judge. I am a magistrate when performing these duties.

Giving the accused his Miranda Warning (You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you), explaining the charges, and setting bail is part of magistration.

Lots of people get it mixed up with arraignment. Arraignment is when the accused goes before the court of jurisdiction judge (usually a district or county court at law judge) and makes a plea.

I am a judge when I am on the bench hearing a case.”

In Texas, the JP hears criminal cases involving minor misdemeanor offenses (class C) such as traffic tickets. The JP may also preside over civil cases where the amount in controversy does not exceed $20,000. The JP also sits as judge of the small claim’s courts, in actions for the recovery of money, which does not exceed $20,000.

Meredith said that “often, the accused will complain that the arresting officer did not read them the Miranda.”

Contrary to crime TV portraying the Miranda Warning as required at the time of arrest, this is not the case in Texas. An arresting office with no intent to interrogate the individual is not required to mirandize onsite. If the arresting officer or detective intends to ask the individual interrogating questions — designed to possibly incriminate — he must give the Miranda warning before doing so.

Setting bail

Getting out of jail is not free. Obtaining a release from jail prior to being exonerated or convicted most often requires some type of money payment — cash bail or a bond payment.

For many accused, the bail amount is the determining factor in whether they are detained in jail or free to return to work and family while awaiting the disposition of their case.

Putman talks about the criteria for setting the bail amount. “The statute that sets out the different things that judges consider in setting bail is Code of Criminal Procedure — CCP17.15. I5. I can read it to you.

‘The amount of bail to be required in any case is to be regulated by the court, judge, magistrate or officer taking the bail. They are to be governed in the exercise of this discretion by the Constitution and by the following rules:

- The bail shall be sufficiently high to give reasonable assurance that the undertaking will be complied with. (So that they come back to court.)

- The power to require bail is not to be so used as to make it an instrument of oppression. (So, they are not just giving them a high bail just to punish them.)

- The nature of the offense and the circumstances under which it was committed are to be considered. (How violent, how dangerous was the offense?)

- The ability to make bail is to be regarded, and proof may be taken upon this point. (Right. So, it’s if you can’t afford very much, it wouldn’t take very much to assure your appearance. If you’re a billionaire, a $1000 bail is not going to motivate you to come back.)

- The future safety of a victim of the alleged offense and the community shall be considered.'”

Justice of the Peace Meredith says that when setting bail, he considers, “the seriousness of the offense — if it a class B or A misdemeanor or a felony influences how I set the bail.

If they have been arrested before, we try to look and see what their criminal history might be. I consider their ability to pay, and I do look at their ties to the community — family, job.

At that point in time, it is just up to me to decide what bail I’m going to set. Bail is set on a case by case basis. There is no set bail schedule.

For a non-violent first offense class B misdemeanor, I usually set those at $500. If it is a class A, I will set it around $1,500. If it is someone who has been in the system a few times, I may set it at $2,500. Of course, when I get into the felonies, I usually get up to $7,500 with $50,000 probably being the highest I’ve done.”

Both Putman and Smith pointed out that their offices are not involved in setting bail which is statutorily the responsibility of the magistrates or the county and district judges issuing the arrest warrants. Putman stated, “We are never in a position of making that decision.”

Numerous attempts were made to talk with several judges for the purpose of this article but were met with no response or a message that they were not interested in responding.

Get out of jail free — almost

Once arrested, there is one way that the accused might get out of jail without an initial monetary payment — a personal recognizance bond, or PR bond. With this bond, the accused is not asked to pay any bail money and are released on their assurance that they will return to court at the set time and place.

According to Meredith, “If it is a class B, maybe a class A, misdemeanor, the accused doesn’t have a criminal history, lives somewhere local with family ties, and I am pretty positive that they are going to show back up for court, I would consider a PR bond. If they live in Wyoming, probably not.”

Some judges, after reviewing all the relevant information, will issue a PR bond on the spot. However, more often the defendant, or his representative, must file a motion with the court — Motion for Personal Recognizance Bond or Motion for Bond Reduction.

Sheriff Smith speaks about conditions that might prompt his office to consider submitting a recommendation to the judge for a PR bond.

“If we need relief in the jail would be a primary consideration. If the offense is non-violent, like theft or forgery, the accused has no criminal history and has ties to the community would be other considerations. If they have a medical condition is another.

We try to get as many with medical conditions as we can out. The reason for that is they cost the taxpayers of Smith Co. a tremendous amount of money, so, certainly, we would submit their names to the judge to try to get them out.

A drug charge, other than a misdemeanor marijuana charge, has always been considered a violent offense such as possession with intent to distribute because of everything that happens around intent to distribute.

None with this type charge are eligible for a PR bond. Those charged with felonies that we might consider submitting for a PR bond would be those with medical conditions and non-violent offenses.”

Per Sheriff Smith’s comments regarding marijuana charges, it is helpful to know:

- Possession of two ounces or less of marijuana is a Class B misdemeanor, punishable by up to 180 days imprisonment and a fine not to exceed $2,000.

- Possession of between two and four ounces of marijuana is a Class A misdemeanor, punishable by imprisonment of up to one year and a fine not to exceed $4,000.

- Possession of between four ounces and five pounds of marijuana is a state jail felony, punishable by a mandatory minimum sentence of 180 days imprisonment, a maximum of two years imprisonment, and a fine not to exceed $10,000.

The PR bond is obviously advantageous in that it requires no monetary payment, but it takes longer to acquire. Also, there is the possibility of conditions placed on the bond, such as a drug test or supervision.

Often, the defendant is responsible for paying the fees incurred with these conditions. Those released on a PR bond, just as with any other type bail or bond, who fail to meet the conditions or appear in court as assigned, are subject to warrants, re-arrest and payment of the original bail amount.

Get out of jail — not free

The bail has been set. How can the accused get out of jail? Gary Pinkerton, Director of the Smith County Pre-trial Release and Personal Bond Office, explains the process.

“Let’s say a man goes to jail for a DWI. His bail is set at $500.

He has three options: He can pay the full $500 cash bail and get out. He can call a bail bondsman and pay the bondsman, normally 10% of the bail amount — $50 in this case — and get out. Or the third option: He can call our pre-trial release office and apply for a personal bond — a PBO bond.

The difference is with the cash payment by the accused. He is taking on full responsibility for showing up at court. With the use of the bail bondsman, the bondsman is taking on the obligation that the accused will appear in court at the set date and time.

With the PBO, our bonds must be approved by the judge with jurisdiction over the case. If the PBO application is approved, then the accused pays a minimum of $20 or 3% of the bail amount. In this case $20 instead of the $500 cash or the $50 to the bondsman.”

It is important to note some differences in these means of getting out of jail.

If the accused pays the full cash bail, Putman says that if he shows up in court every time he is ordered to appear, he will get the entire amount back.

If the accused uses a bail bondsman to post his bond, he does not get any of the bond fee, usually 10% of the bail amount, back. Financially, the PBO bond appears to be the better option; however, it comes with eligibility requirements as well as a variety of possible conditions.

Pinkerton explains the process for securing a PBO bond through his office.

“Pre-trial office was established in Smith County in 1979, and I have been the director since 2014. The inmates will normally call us; however, we have a lady in our office who comes in every morning and verifies who has been jailed recently and have not called a bonding company to try to bond out.

If they have not called a bonding company, we will talk with them about a PBO bond. Basically we go interview an inmate to see if they have ties to the community, and if they meet eligibility criteria: they must be a resident of Smith Co. or reside within a 50-mile radius, in jail on local offenses, and must not be on probation or parole.

If these criteria are met, we assure that they are willing to meet the other criteria: they must report to our office every week until their case is disposed of; appear in court for all scheduled court appearances; refrain from unlawful conduct; notify our office immediately of any changes of address, telephone number or employment; and complete a client travel form in the event they plan on going out of town.

We have to do a background investigation which entails looking at their criminal history and verifying ties to the community — employment, family, community involvement. We proceed with those inmates we think will qualify and prepare a report for the judge of jurisdiction.

If the judge approves the PBO bond, the accused must sign an agreement, which is notarized, stating he will abide by our rules and regulations as well as any conditions added by the judge.

We will interview any accused, but there are some based on their prior histories that will automatically be disqualified. If we have someone who is a repeat offender and charged with a felony, we have to look at community safety in our decision making also.

Approval of the PBO bond is solely up to the judge. For example, a person is arrested for marijuana possession and seeks a PBO bond. If the judge sees that there is no extensive history, he will probably approve it.

But if someone has been in jail eight times for possession of marijuana, the judge will probably not approve it because the person is not learning anything and is continuing the same old cycle.”

According to Pinkerton, in some cases the judge, dependent upon the type and severity of the alleged offense, will place additional conditions on the bond.

If an offense involves drugs, the judge may add a required weekly drug test as a condition. If an assault is involved, the judge may put a protective order in place setting limits on the proximity of victim and accused. A judge may require the accused to attend community supervision conducted through the probation department.

Due to the fees involved, a PBO bond with conditions is problematic for the accused who was unable to afford the cash bail or pay a bail bondsman in the first place.

According to Terrie Lindsey, Smith County Adult Probation Supervisor, the fee for a drug test is $10 or $40 a month, regardless of the number of tests.

The fee for community supervision is $60 per month. Given this, the accused could be responsible for $100 a month in fees for an unknown number of months until his case goes to court.

This begs the question: Is a PBO bond helpful, or even feasible, for someone who could not afford bail or bond?

The Smith County Pre-Trial Release and Personal Bond Office is tasked with assisting in the reduction of overcrowding in the county jail by allowing qualified defendants an opportunity to be released on personal bond while pending disposition of their case.

According to Pinkerton, from Jan. 1- Sept. 30, 2020, his office reviewed and disseminated 5,101 bonds, including all types of bail and bonds originating from the Smith Co. Jail, to the corresponding courts.

In that same time period, his office staff interviewed 375 inmates about their eligibility to secure a PBO bond. Of those 375, 31% or 116 inmate files were prepared and submitted to the County Court at Law and District Courts for PBO bond consideration.

Judges approved PBO bonds for only 18, or 16%, of the 116 cases considered, resulting in only 5% of those initially interviewed being granted PBO bonds. Of the 18 PBO bonds granted, two defendants have failed to appear in court as required.

Who remains in jail?

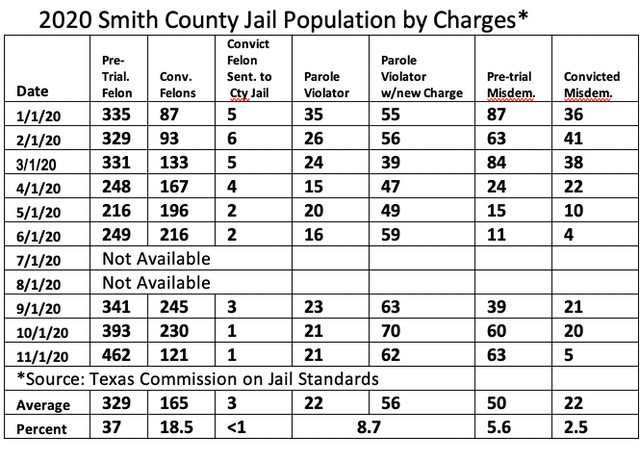

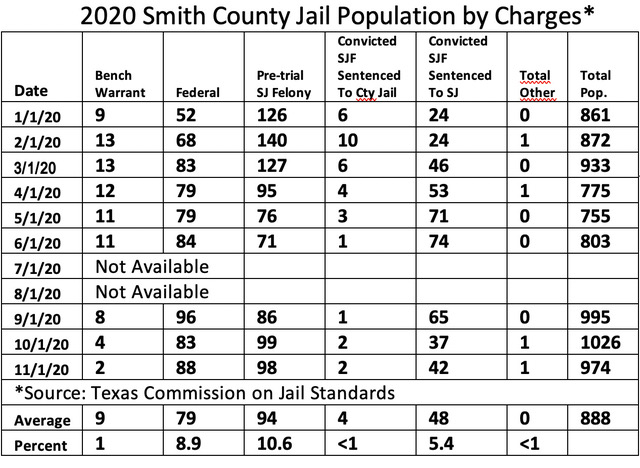

An analysis of the Smith Co. Jail population by type of charge for the nine months of available data in 2020 offers a snapshot of who is populating our jail.

The average monthly jail population has been 888 inmates. Again, using a monthly average, 329, or 37%, of those 888 are pre-trial felons being held awaiting court appearances.

Another 50 inmates, 5.6%, are pre-trial misdemeanor offenses while 94, 10.6%, are pre-trial state jail felons. This results in a monthly average 473, or 53% of the jail’s population, are being held awaiting trial.

Why are so many inmates being held pre-trial?

Recall Sheriff Smith’s factors driving the jail population:

- Individuals who are unable to make bail or secure a bail bond;

- Previous offenders out on bond getting re-arrested resulting in an even higher bail. According to Smith, 90+% of the jail population are repeat offenders.

- More concentrated law enforcement;

- The higher number of felony offenders, which leads to higher bail and longer jail stays.

Using Smith’s 90% repeat offender statistic and our averages, 799 of the 888 inmates are repeat offenders with typically higher bails, which means even fewer inmates are less likely to afford their bail, either cash of bond.

This, along with longer jail stays, results in this group of inmates remaining a constant higher proportion of the jail population.

In our scenario of averages, parole violators without or with a new charge constitutes 8.7% of the jail population. This group of inmates are more likely to not be eligible for bail and thus remain a population constant.

Putman says the federal government has a system of risk assessment, in which one is detained and not getting out pre-trial or released without a bond at all, but with a personal assurance to return to court. That would mean that our 79 federal detainees will remain in the county jail.

Where is the “wiggle room” in lessening our current jail population and keeping it lower?

In the near future, as COVID-19 restrictions are removed, the convicted felons and the state jail felons convicted and sentenced to the state jail will likely be transported to other facilities — TDC or state jail.

Those inmates being held pre-trial for misdemeanor and state jail felony offenses are most likely ones who would be eligible for bail and bond release.

Why are these folks still in jail and contributing to the overcrowding? Sheriff Smith response points to the inability to make bail or secure a bail bond.

Questions to consider moving forward

The jail system and bail and bond process is complicated and deserves thorough treatment. Researching and compiling this explainer has prompted more questions I hope to pursue in the future. As an engaged resident, this information needs to be transparent and understood.

- Why are bail amounts unaffordable?

- Why would some inmates choose to stay in jail?

- What are the high costs of bail — to the detainee, the county and the community?

- What are our community and criminal justice leaders saying about bail reform?

Brenda McWilliams is retired after nearly 40 years in education and counseling. She has been featured in Out of the Loop, the Tyler Loop’s storytelling series, and has reported for The Tyler Loop on a local high school’s glorification of the old South and white supremacy. When not traveling she fills her days with community, charitable, and civic work; photography; writing and blogging at Pilgrim Seeker Heretic; reading, babysitting grandchildren, and visiting with friends. She enjoys walking at Rose Rudman or hiking at Tyler State Park. Brenda and her spouse, Lou Anne Smoot, the author of Out: A Courageous Woman’s Journey, have six children and seven grandchildren between them.

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.