Five months after legislature created it, Smith County administrators prepare to shuffle the courthouse furniture to make room for the new 475th District Court.

The addition gives Smith County its fifth venue for hearing civil and felony criminal cases — a historic note 44 years in the making.

But County Judge Nathaniel Moran can’t decide whether to celebrate finding the physical space to accommodate another courtroom or to bemoan the fact the county’s growing backlog necessitates it.

“We are extremely happy we are able to accommodate another court,” Moran said. “It doesn’t happen by accident. It takes a lot of planning. The great thing about this is we had a great bunch of district judges who helped us through the process.”

The backlog, he said, is the byproduct of trying to meet the needs of a growing population with decades-old resources. The pandemic only added to the problem.

“If you want to administrate justice correctly, then we have to move these cases through court,” Moran said.

Being forced to wait for trial isn’t fair for crime victims or defendants and delays just cost the taxpayers more, he said.

HB 3774, which was signed into law in June, officially opens the 475th District Court beginning Jan. 1, 2023. Construction on a new courtroom is scheduled to begin Dec. 6, and Gov. Greg Abbott is expected to appoint a new judge within the next year.

Statistical support

The last time Smith County expanded its judicial system was in 1977. For decades, the 7th, 114th, 241st and 321st district courts seemed sufficient to handle the load, but a 140% growth in population (from 100,000 to 233,000) since then began to take its toll. Court officials struggled to keep up, and when courtrooms shut down during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the backlog forced officials to look for relief.

A six-page analysis report presented to county commissioners earlier this year shows a steady increase in civil cases filed in Smith County between 2015-2020. In 2019 alone, the courts received 1,556 new civil cases and cleared 1,147 — but left 1,777 cases pending (including carryover from previous years) for a 74% clearance rate. The state average for clearing civil cases was 89%, according to the analysis.

Smith County tallied a 91% clearance rate of civil and criminal cases combined in 2019 but still came in 5% less than the statewide average, according to the analysis report.

Concerning the criminal caseload, the report concluded “despite increasing work output … the workload mounts faster than four courts can handle.”

The county also has experienced a “steep rise” in jail inmates waiting court hearings on felony charges — a situation that accounts for over half of the total jail population. A new jail opened in 2012 already has reached capacity, forcing Smith County to pay to house inmates in other counties.

In 2019, Smith County averaged 428 inmates who were awaiting felony trials. At a cost of $58 per day for each inmate, housing those awaiting trial adds up to $9.2 million a year, according to the analysis.

Finding room

Under a plan Moran proposed, the 321st, which has jurisdiction in family-law cases, will be moved from the main courthouse to a new courtroom under construction on the fifth floor of the courthouse annex across the street.

Workers with Casey Sloan Construction of Hallsville are schedule to begin remodeling the space to accommodate a judge, two court coordinators, a court reporter, a jury and spectators. The $508,198 project includes two new bathrooms.

The space vacated by the 321st in the main courthouse will be designated as the new 475th courtroom.

Moran told commissioners earlier this year the shuffle makes sense because offices for agencies that use the 321st — such as Child Protective Services — also are located in the annex. Locating the 475th in the main courthouse keeps it close to related departments, such as the district clerk’s office and the tunnel used to transport inmates from the jail, he said.

Although the state funds the judge’s salary, the county will be responsible for providing the space and funding for staff support.

The new arrangements likely will remain in effect until county officials address the possibility of building a new courthouse, he said.

Courtroom history

The last time the Texas legislature answered the call for a new court in Smith County was in 1977, when the 241st District Court was created. Officials relocated the second-floor law library to accommodate a courtroom — one of the physically smallest of the district courts.

During its inaugural year, the 241st was the site for a capital murder trial that has become one of Smith County’s most controversial cases.

The trial of Kerry Max Cook took only a few days but his conviction and death sentence for killing Linda Jo Edwards remains unresolved on appeal for more than four decades. Today, Cook is a free man awaiting a final court decision on actual innocence.

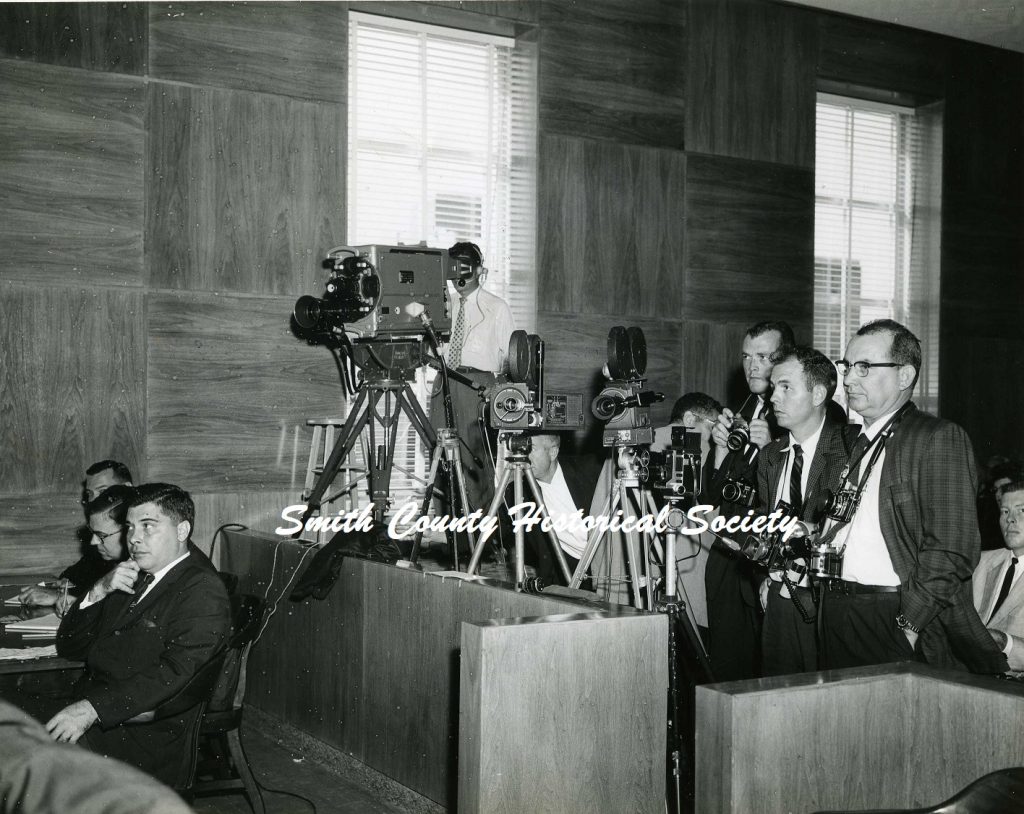

Smith County’s first district court — the 7th — was created in 1876 and left its mark in U.S. history in 1963 with the fraud conviction of west Texas financier Billy Sol Estes. His trial was moved to Tyler due to extensive publicity. Ironically, his conviction was overturned on appeal after judges ruled television cameras allowed in the courtroom prevented him from receiving a fair trial.

The 114th District Court, created in 1933, also has had its share of headline-grabbing criminal trials. Its entry into the annals of Smith County history includes the first district court to allow the return of cameras in the courtroom. Judge Cynthia Kent opened the 114th District Court to media cameras in the 1990s.

The 321st District Court, created in 1957, is the county’s only family law court — hearing cases involving divorce, child custody or child protective services. In 1985, Judge Ruth J. Blake became the first female district judge in Smith County. She served on the 321st bench until her retirement in 1997.

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.