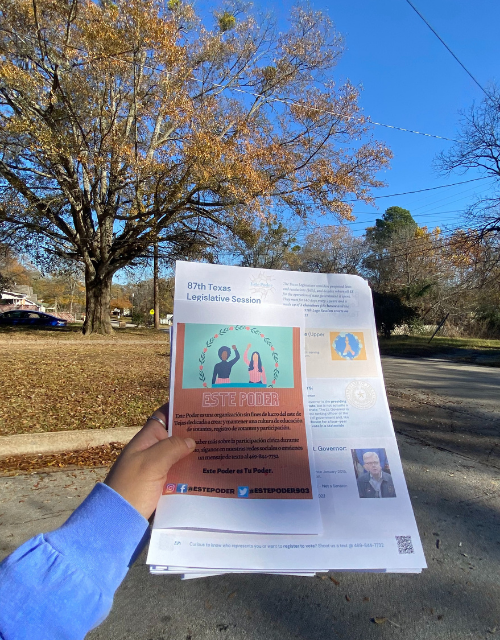

In January 2020, three young East Texas women — Lina Ortega, Belén Iñiguez and Emily Pinal-Oviedo — created a local, nonprofit organization called Este Poder, “this power.” The Loop sat down with them last week to learn more.

“Este Poder’s mission is to cultivate civic engagement in rural communities, specifically communities of color,” Ortega said.

“We want to focus on our communities that have been overlooked time and time again. We want to talk to them about real issues that affect them like wealth and income inequality, lack of healthcare. We are non-partisan; we want to progress our communities.”

All three of Este Poder’s founders share a background of registering voters, canvassing neighborhoods and organizing events to boost civic engagement.

After graduating from UT Tyler, they saw a need to continue.

Ortega explained what propelled them to create a new organization.

“Around the 2018 election cycle, we were a little discouraged. We saw the momentum die down and people not being registered to vote as much. There was some increase in voter turnout, but we all know that voter turnout could be higher,” she said.

“So we kind of were like, ‘Okay, let’s create an organization where we keep the energy going year round. We want to keep talking about elections. We want to keep talking about registering to vote. We want to keep talking about our communities.’”

Choosing a name to reflect their mission took time.

“Deciding our name was hours of deliberation,” said Iñiguez. “We thought about it very, very hard, but it was actually one of our board members and my wife who thought of it. In Spanish, ‘este poder’ means ‘this power,’ but it has double meaning, because the word este also means ‘east.’ So, the power of the east.”

Iñiguez continued, “[Este Poder] is personal to us and it’s personal to specifically Hispanic communities living in East Texas, to know that we have power and can be part of this power.”

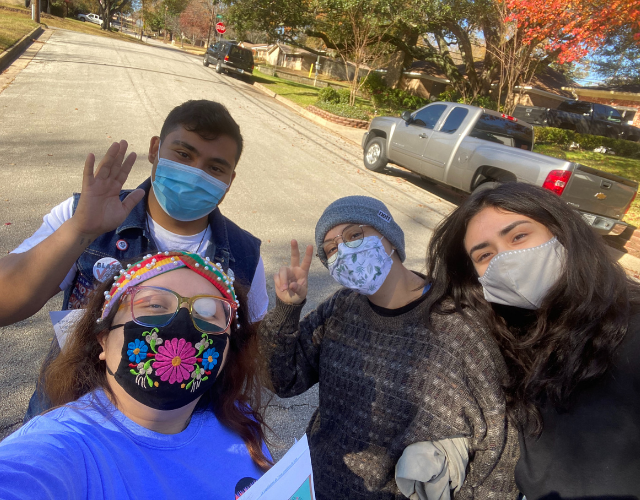

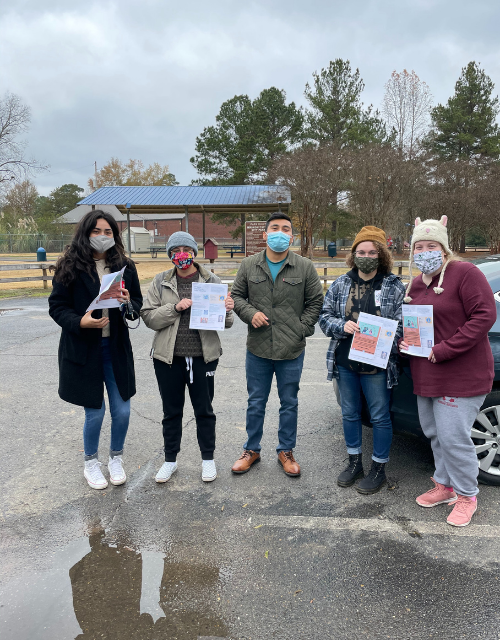

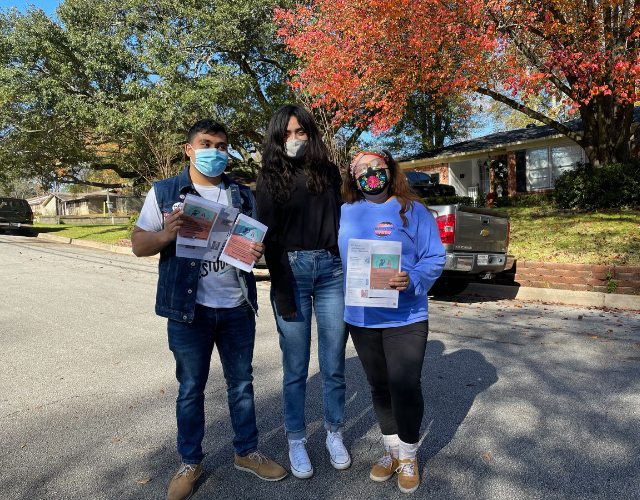

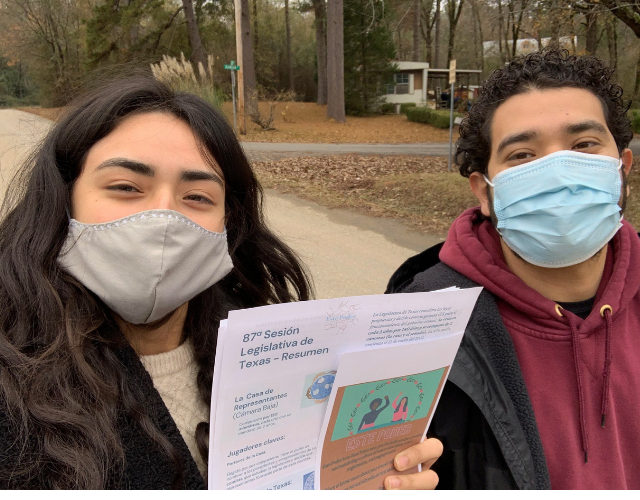

In the last year, getting the word out about voting and civic engagement has been trying due to COVID risks. Even so, the three founding members, along with eager volunteers, have donned their masks and gone door to door throughout East Texas, dropping literature and answering questions for residents in rural Black and Latino neighborhoods.

Their most recent literature drops took place in Mineola and Waskom.

Iñiguez talked about the level of information sharing and civic engagement in those areas.

“We chose Waskom, because I am from Waskom, and I know firsthand what it looks like in terms of demographics and who is talking to us. No one’s talking to us. What kind of money is being spent there to engage them politically or civically? None,” she said.

There’s a message Iñiguez hopes to communicate to small, underserved East Texas communities.

“We just want to be like, ‘Okay, there’s a different outlet. There’s different ways we can achieve progress for everybody.’ And hopefully that’s what we’re doing in our small communities and rural areas where voter turnout is very low. We’re asking ourselves, ‘Why is that?’ It’s probably lack of information.”

Iñiguez said, “Sometimes people don’t want to change, but in reality, no one’s reaching out to them or talking to them. We’re showing that getting civically engaged is not a chore, it’s so much easier and it affects all of us.”

The response during the recent literature drop-offs left an impression.

Pinal-Oviedo said, “There was one lady in particular in Mineola who told us, ‘No one has ever come knocking on my door.’ She was telling us how she has daughters in high school, and asking how do they even get registered and where do they go.”

Pinal-Oviedo added, “Especially in these smaller, unreached communities like Waskom and Mineola, as you encounter households, you ask, ‘What are the needs?’”

There are some needs Pinal-Oviedo sees time and again in small East Texas neighborhoods of color.

“There is a lack of transportation, for sure. There’s a lack of voting centers in those areas. A lack of education is a huge issue.”

Some towns in East Texas are showing promise, however, by their positive response to community engagement. New chapters of Jolt, a statewide nonprofit that “increases the civic participation of Latinos to build a stronger democracy” are starting in East Texas.

Pinal-Oviedo said, “In Sulfur Springs, I have a friend, a mom who is 20 years old. She’s a rock star. She reached out to me before the Beto campaign in Sulfur Springs and said, ‘Hey, I heard you started Jolt at your college. I want to do the same thing at Texas A&M Commerce.’ I told her how to do it, who to reach out to. She did it.

“And then as time goes on, she ran for city council, the youngest Latina ever in that little town to run for city council.”

Knocking on doors in Jacksonville encouraged Pinal-Oviedo, too.

“In Jacksonville, I created a canvassing event. Five people showed up and we went to a primarily African American neighborhood. We were scared because there were a lot of loose dogs, but we were like, ‘We’re just gonna do it.’”

Ultimately, Pinal-Oviedo was encouraged by the Jacksonville canvassing.

“When we were working, we were really, truly working for the people. We were in areas we’ve never been to before.”

Pinal-Oviedo says the groundwork of knocking on doors and speaking to households is vital to Este Poder’s mission.

“Our work is mostly piecemeal, door by door, or they’ll go to the nearest college to be involved. When we know there’s not a college, it has to be door by door.”

Ortega said, “It does have to be door to door, initially, at least, to make it more personable. I guess I want to be more of a connection. And then we can of course escalate to bigger audiences. That’s the bigger goal.”

Ortega explained why going door to door matters to her and how COVID has diminished interaction.

“I want to have a conversation with somebody, more heart to heart. It shows that we really do care about you and your household, like we want to make it better for everybody. I personally love door to door, it’s the best. But as of right now, we’re just doing lit drops. Because of COVID, we’re trying to minimize contact.”

While all three of Este Poder’s founders have a background in voter registration, each had a different story that began their passion for civic engagement.

As a teen, Pinal-Oviedo’s encounter with protesters in Tyler ignited her involvement.

“There was a protest on the Loop on Broadway. A group of individuals were against immigration and they were saying things like, ‘Wetbacks are not welcome here.’

“My dad dropped me off and he’s like, ‘Do you really want to speak with them? I’ll stand beside you.’ I was talking to them. I was like, ‘Why do you feel so strongly about us? What’s up?’”

The protesters began disbanding soon after Pinal-Oviedo’s arrival.

“I’m sure I wasn’t the reason why they left, but I guess they were tired of it. I don’t know, but I had a good conversation with them. I posted that on Instagram and that day.”

Pinal-Oviedo’s Instagram post created a stir.

“[Social media comments said things] like, ‘Flick them off, honk at them when you pass by,’” said Pinal-Oviedo.

One particular comment impacted Pinal-Oviedo the most. Tyler organizer and activist Delila Reynoso saw the online reactions and challenged them.

Pinal-Oviedo remembers her post saying, “Is this really the way we should counter react? You know, are there other ways we can participate and have a voice other than just passing by and flicking off.”

Later, Reynoso reached out to Pinal-Oviedo and encouraged her to help people vote.

“She told me, ‘You know, you could become a VDR (Volunteer Deputy Registrar).’ I started contacting my friends, asking ‘Are you registered to vote?’ It grew from there,” Pinal-Oviedo said.

“And I got involved with Jolt, and after that, [I worked with] the Beto campaign.”

Thanks to Pinal-Oviedo, Ortega also became a VDR.

“I was a VDR in Smith County and Wood County. I was registering everybody that I talked to,” Ortega said.

“I started having conversations all the time about what is happening, the importance of voting and talking about where to go vote, making it easier.”

Ortega’s help did not stop at providing information.

“At one point, we were driving people to the polls, trying to make it as accessible as possible for anybody.”

Iñiguez’s start was also through involvement with Reynoso.

“What really kick-started me was being involved in immigration rights and JFON, Justice for Our Neighbors, with Delila,” said Iñiguez.

“In Austin at a DACA summit, we had the opportunity to hear [about] Jolt, a brand new nonprofit. I asked, ‘How do we get a chapter of Jolt into UT Tyler?’ And so I kind of kick-started that.”

When asked what work is most important now, Pinal-Oviedo has set a high bar.

“I have to make sure that our communities are taken care of in every aspect that I can help with. That’s my goal.”

Iñiguez added, “I want to be in Texas politics, specifically state politics. It’s necessary to lay down the groundwork before we jump into it.

“At this point in time, we’re so divided right now. And there is no groundwork for uplifting the votes of Black and Hispanic communities right now in rural counties here in East Texas. I’ve definitely thought about running against Chris Paddie or Brian Hughes.”

When asked about the nonpartisan nature of Este Poder, Ortega explained, “A lot of these policies, at the heart of it, they’re non-partisan. They affect everyone regardless of your political background.”

Ortega said, “What we try to provide is information on what those policies are, because a lot of times politicians pass them, but we don’t even know what they mean or what they say or how even they’re going to affect our community.

“We provide that background for people who are then able to make their own judgments from that.”

In the future, Este Poder’s three founders have big dreams.

Ortega began, “A dream we have is to make enough movement and apply enough pressure to Texas politics that we have automatic registration at the age of 18. That is one of my personal goals, to inform our community that this is a possibility.”

For Pinal-Oviedo, moving forward happens in East Texas high schools.

“I think [my dream] is making sure that the civic engagement culture is already in place, especially in high schools. That would be a goal of mine: that we don’t have to worry about them leaving high school and not knowing what they can do as a citizen, what they can do as their duty.”

Pinal-Oviedo added that some Texas high schools need a push to do voter registration.

“By law they’re required to have voter registration events in high school twice a year. It doesn’t happen in our high schools, especially in rural communities. We have to go and put pressure and remind them that it’s required.”

Iñiguez’s hopes center on voter access.

“That’s just so crazy to me that we live in the US, [where] accessibility should be no problem, but it is a problem. I envision an America where voting is not that big of a deal or where voting is common and people can do it easily,” said Iñiguez.

As for how community members can help, Pinal-Oviedo said, “We’re just starting off. And if there’s any support that anyone is willing to offer us in terms of volunteering or monetary support or anything, we welcome it. We’re brand new and we’ve never done this before.”

Pinal-Oviedo keeps the long term effect of civic engagement in East Texas in mind.

“If we continue to do this work, there is going to be a big difference in four years.”

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.