Author and anti-racism activist D.G Montalvo has focused his research and efforts for change in Tyler, Texas, his hometown. He recently spoke to The Tyler Loop about his book, “Tyler’s History of White Supremacy,” published in 2021. Montalvo said racism in Tyler contributed to the foundations of the city Tyler is today.

Montalvo believes Tyler is due for a “reckoning with truth,” and for racial reconciliation, residents and city leaders must be honest about Tyler’s history.

Montalvo’s books include a timeline of the events, people and evidence of white supremacy beginning in the early 1800s and ending in the 1970s. Montalvo connects these to the present day to show readers how the past influences individuals and culture for years afterward.

Montalvo believes conversations about racism can change the future of Tyler.

“I’d like to believe that Tyler is full of well meaning, good-natured people. Conversations about race and racial justice can help bring those good-natured, people-loving citizens out to actually help shape Tyler in a purposeful way, instead of accidentally moving the ball forward with the status quo,” Montalvo said.

He said he was motivated to write the book because Tyler has lacked conversations about its history of white supremacy.

“One reason I wanted to write the book is that we haven’t had conversations about what happened. You can’t deny that it’s always in the background. It’s something that needs to be resolved.”

As an organizer for the We Remember Tyler, an organization advocating a lynching memorial, Montalvo and others have requested a memorial honoring the four men lynched on Tyler’s downtown square, as well as the dozens of other victims murdered due to racial prejudice in Tyler. The new monument would be placed on or adjacent to the new courthouse that is set to begin construction in 2024.

“The lynching Memorial would probably be a granite or marble plaque that shares a short history of the three victims of racial lynchings that happened right here on the square,” Montalvo said. “This is such an important step–and not our last step, the first step–in acknowledging that we haven’t had a city-wide conversation about some of our ministries that preach reconciliation.

Current monuments at the downtown square include the policeman’s prayer and a Confederate soldier memorial erected in 1969, which counts “loyal slaves” as part of the Confederate population.

“This step, this memorial, is acknowledging lynching victims, acknowledging the people who experienced the worst of hate mob violence,” Montalvo said. “Some of our communities that experienced racial terror need to know that we’re all committed to change, and acknowledgement would help make that possible.”

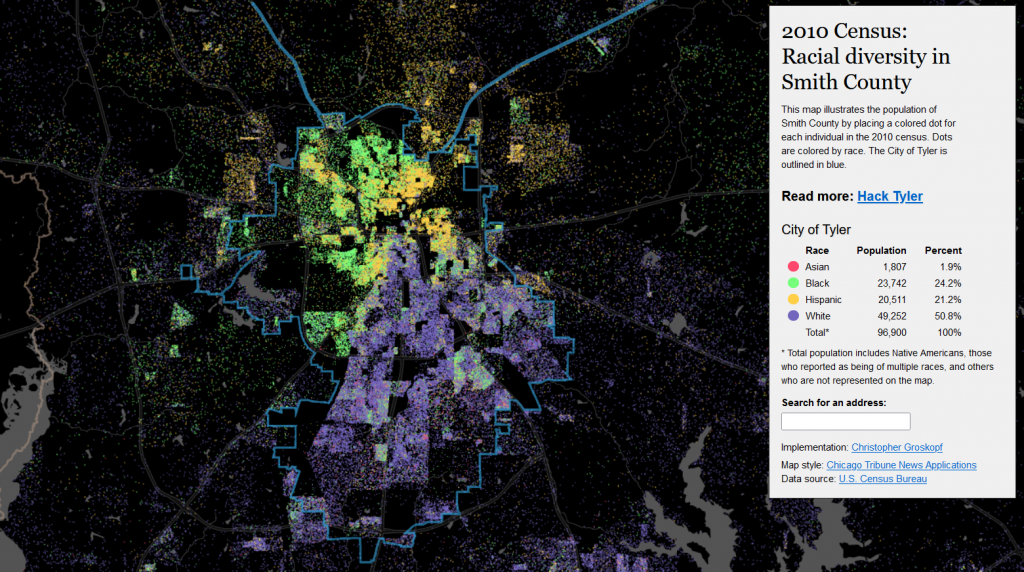

Montalvo identifies Koch & Fowler, a Dallas-based engineering firm, as the city planners responsible for creating the plan to segregate the city of Tyler in 1929. Church services were isolated to certain areas of the city for Black citizens while other Black neighborhoods were uprooted for white development, resulting in a racial divide between the north and south sides of Tyler that persist today.

“There’s entire places where you don’t see Black investment and Black homes,” Montalvo said. There is undeniable proof today that shows we’re segregated because of what has happened in the past.They lured people away through legal, creative and clever means in order to keep them divided.

“Tyler’s History of White Supremacy” resulted in significant backlash aimed at Montalvo.. Montalvo recounts his harassment urged by a local Facebook page while he was researching for his book.

“When people found out that I was doing that sort of research very specific to Tyler Smith County, people who have been multi-generation, longtime residents of Tyler were very vocal about how they felt about my research and what they thought my motives were,” Montalvo said. “They thought I was being purposely divisive and racist. I really believe in Martin Luther King Jr’s idea of a beloved community, and they thought I was trying to divide the community.”

Among the threats were repeated harassment from an unnamed automotive store owner, who threatened to bring physical harm to Montalvo and repeatedly demanded to meet in a public auditorium to debate the subject of the book.

“A nonprofit actually donated cameras to us because they saw what was happening. They installed an alarm system for our house because the threat of violence was that high,” Montalvo said. “We’re not advocating racial violence as the solution for injustice in the world. We’re advocating non violence, truth sharing, reconciliation, healing – and yet, as the story keeps getting out, the more it seems that violence seems to be a part of the extreme right wing answer to the injustice of history.”

Dissent against “Tyler’s History of White Supremacy” was not relegated to those who disagreed with Montalvo’s message. Members of the Black community feared publishing such a book would cause outlash targeted at minorities.

“I met this young Black activist at a coffee shop in downtown Tyler, and she was like, ‘Please don’t do this. They’re gonna go crazy on this,” Montalvo said. I had to think long and hard to talk to a lot of other people about that comment, because I didn’t want that to possibly be the case.”

It was only after significant social change during the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 that Montalvo felt comfortable enough to publish the book. He credits the change to the name of the school formerly known as Robert E. Lee High School as the moment he knew Tyler was changing for the better.

“It was public sentiment that helped make that possible, that shows that there’s been a shift of some sort,” Montalvo said. “All the youth that were behind the movements shows there is a new story that is being written for Tyler.”

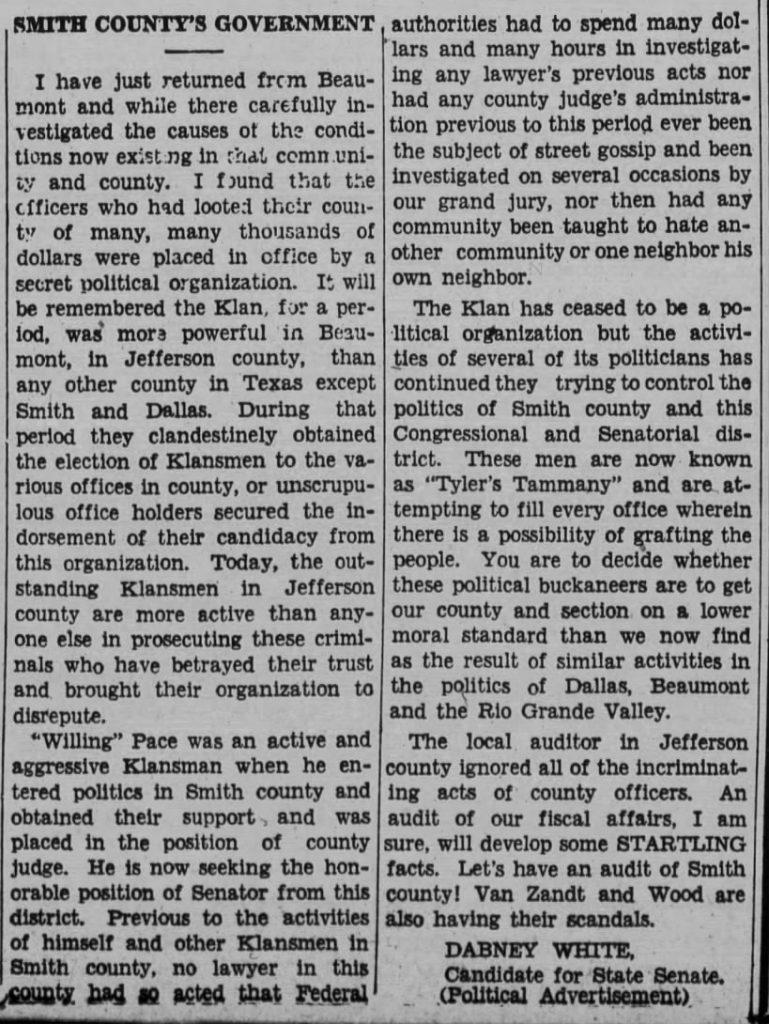

In his book, Montalvo touches on the history of the Ku Klux Klan’s chapter in Tyler. He cites an ad from the Tyler Morning Telegraph in 1932 stating the clan had the most influence and power in Dallas County and Smith County. During that time, Smith County Judge William D. Pace rose to power as a Klan-affiliated county judge for three consecutive terms.

Clipping from The Tyler Morning Telegraph, courtesy D.G. Montalvo.

Montalvo’s book ends with a call to action for readers, urging them to seek truth and reconciliation by prompting a dialogue about race and prejudice. Montalvo hopes his work is the start to a long road of healing and change.

“It takes acknowledgement and self awareness in order to make change,” Montalvo said. “It seems we’ve made a social decision as a society to never address the Civil War, Jim Crow, the racial lynchings that took place and the history that’s happened right before our eyes. It’s kept silent. It’s something that needs to be addressed, so that we can move on and truly become, like Martin Luther King, Jr. said, a beloved community.”

Jude Ratcliff is a third year student at the University of Texas at Tyler, where he studies journalism and criminal justice. His passions include reading, chess and photography. It is his hope to use journalism to strengthen the community and uphold democracy and to one day become an investigative reporter while researching prisons and the justice system.

Love what you're seeing in our posts? Help power our local, nonprofit journalism platform — from in-depth reads, to freelance training, to COVID Stories videos, to intimate portraits of East Texans through storytelling.

Our readers have told us they want to better understand this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. What systemic issues need attention? What are are greatest concerns and hopes? What matters most to Tylerites and East Texans?

Help us create more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler. Help us continue providing no paywall, free access posts. Become a member today. Your $15/month contribution drives our work.