In 2017, the Loop ran a provocative article on the immense racial wealth gap in Tyler. Housing forms the basis of wealth in the U.S., and as the article shows, the same holds true for our Rose City. The article also documents a few of the housing policies and mechanisms that have intentionally created, widened and perpetuated the wealth gap both across the nation and locally.

In large part, the wealth gap in housing creates the wealth gap between Blacks and whites. In this article, I attempt to tell the story of housing in Tyler through the lens of race, exposing the racism that creates our city’s racial wealth gap and which belies much of Tylerites’ current living conditions.

To help me better understand Tyler’s attitudes and practices in housing, I created a survey. Please take a moment either now or after you read this article to read people’s diverse and transparent responses.

Here I write solely on racism in housing, but in the U.S., racism pervades almost every aspect of our society. Because of this, I hope that passionate Tylerites will carry last summer’s momentum forward and document racism that hurts Tylerites in other aspects of life, such as in criminal justice, education, jobs and healthcare. My hope is that injustice may be fully addressed locally.

A special thanks to Vicki Betts, Darryl Bowdre, Amori Mitchell, Cornelius Shackleford, Terry Bonner, Julie Gobble, Lee Hancock, DG Montalvo and Mary Claire Neal for their contributions to this project.

Tyler’s early years

Shortly after Texas was annexed by the United States on February 19th, 1846, the Texas State legislature authorized the city of Tyler on April 11th, 1846. On February 6th, 1847, commissioners appointed by the Texas State Legislature bought land for the city from a white man named Edgar Pollett, and Tyler’s physical infrastructure was laid out in 28 blocks around a city square.

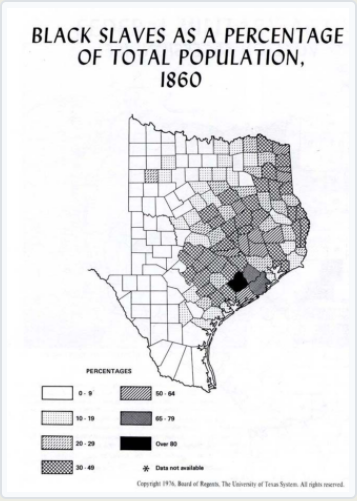

In the wake of the U.S. annexation of Texas, white settlers from the Old South flooded in. Many of these settlers brought with them the institution of slavery and enslaved Black people.

As in much of East Texas, Tyler’s economy depended heavily on slavery. White slaveowners coerced enslaved Black people to grow cotton, then the most valuable commodity in the Atlantic world. In its early days, Tyler depended heavily on the slave-fueled growth, harvest and sale of cotton. In 1824, Stephen F. Austin stated, “The principal product that will elevate us from poverty is cotton, and we cannot do this without the help of slaves.” In 1860, enslaved Black people constituted more than 35 percent of Tyler’s population of 1,021. The enslaved usually stayed in quarters or compounds on their slaveowners’ land.

After Juneteenth declared the end of chattel slavery in Texas in 1865, Black Tylerites began building homes in the fledgling town. The October 24 edition of the Galveston Daily News in 1882 reported that segregated “public schools in Tyler opened with 256 in the white school [Tyler High School] and 146 in the colored school.” There is only a very small number of surviving documents before 1900 because around 1908, the Tyler newspaper office caught fire and burned.

Starting in the early years of the 20th century, evidence of the intentional segregation of Blacks and whites can be found in local newspapers:

- In 1906, the Tyler Daily Courier-Times ran an announcement on its first page.“No lots will be sold to colored people at South Park Heights.”

- In 1910, the Courier-Times ran an ad for a Cotton Belt addition, streets running south to East Erwin, others connect to North Tyler and Cotton Belt grounds, South Frontage is on East Line, “to be sold to white people only.”

- Also in 1910, H. E. Byrne bought an 11-acre block of land adjacent to Texas College in order to “create lots for homes for patrons of Negro school.”

- In 1911, a year later, Herndon estate plots Academy Heights, an area which extended “ten or twelve broad streets” around Colored Baptist Academy and close to Texas College (then called Phillips University), “for colored gardeners and truck growers.”

- Later in 1911 two more ads went up: one for lots in Bellwood Heights, designated “colored only” and one for lots in Summit Heights in Northeast Tyler on Winona Road, ownership and use of which were “strictly limited to white people.”

- In 1912, First Baptist Church downtown posted a job ad looking for “white men only,” so it is doubtful that Black people were allowed to live near the church.

- In early March of 1913, a “threatening letter [was] posted on [the] house of Harmon Neal (colored) on Paul Street, warned him not to live on the north side of Paul Street.”

- The Tyler Daily Courier-Times in 1913 quoted a Big Sandy’s J. P. Hart, “Tyler is famous the world over for many men and virtuous wommen [sic], and as the place where the man who dares to talk of social equality of the races is regarded as a Judas Iscariot. White Supremacy’s home is in Tyler.”

- In 1928, white Tylerites set fire to a Tyler Black man’s house as a warning not to build in a white neighborhood.

- In 1929, the Tyler Daily Courier-Times runs a story on the front page: “Darkey comes home and finds three ‘redmen’ digging hole in yard. Was it a grave? Looks like it.”

Tyler’s city government gets involved

Although intentional racial segregation had been implemented and enforced for decades by private land companies and developers and backed by the Supreme Court, through the 1920s there is no evidence that the Tyler city government was actively involved in segregation in Tyler. This changed in 1931 with Tyler’s new city plan. For help with a new, more detailed and more precise city plan, the City of Tyler government contracted outside help.

Three years prior in 1928, Austin was also developing a city plan. Since the Civil War, Austin consisted of pockets of Black neighborhoods dispersed within a predominantly white city, an arrangement due in large part to racist private restrictions. According to the Austin-American Statesman, Austin city officials had “lost their most effective discriminatory tool in 1917, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that cities could not use zoning laws to segregate by race.”

So the city of Austin turned to a consulting engineering firm from Dallas called Koch and Fowler to draft a new city plan in 1928. Koch and Fowler argued that although zoning laws were no longer an available option, the city could withhold municipal services to Black people everywhere in the city except for certain zones. Indeed, the Austin 1928 city plan did just that, designating an area east of I-35 as the “Negro District” and withholding services to any Black person living outside of the area, which coerced most of the Black population of Austin to move there.

Three years later, amidst the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation’s racist redlining policies segregating cities across the country, the City of Tyler hired the very same Koch and Fowler to author its 1931 plan.

They wanted to segregate Tyler, but still Buchanan v. Warley barred explicit racially exclusive zoning. Again, Koch and Fowler pulled their trick. According to the 1931 city plan, Tyler’s Black population up until that point was “scattered all over the city.”

In response, the firm “recommend[ed] uprooting black neighborhoods near downtown for white development and strategically placing all ‘colored schools’ and parks to keep black families in isolated areas of northwest, southwest and central Tyler. That will achieve white leaders’ goal of citywide segregation without risking claims about unconstitutional restrictions, a Dallas consulting firm [wrote], because ‘It simply will not be convenient for a negro family to live in any other section of the city.’ ” If a Black area spreads into a white area, “it will very soon depreciate the white residential property.”

In 1945, Tyler again went back to Koch and Fowler for a new city plan. Lee Hancock’s “Robert E. Lee High School, race, and segregation in Tyler: a 130-year timeline,” notes, “The updated … plan recommend[ed] removing Emmett Scott High School from Border Street and building a new school and park several blocks west to protect Tyler’s ‘present dividing line between whites and negroes.'”

Both of these plans were carried out. The plan also recommended a second Black high school be built adjacent to Peete Elementary, to be centrally located to serve the Black area of southwest Tyler, as well as a park, now W.E. Winters Park, directly to the south of that to serve as a buffer between the Black neighborhood to the north and west and the white area south of Lindsey Ln. and east of Englewood Ave.

The plan further recommended a Black park south of Lincoln Street and west of Englewood Street, as well as Black parks just west of the old Emmett J. Scott location, just north of Texas College, and in a small Black neighborhood north of Erwin and east of Poplar-Beckham.

The next year in 1946, the Tyler ISD “school board discusse[d] a $225,000 stadium for Tyler’s white high schools and junior college. The district can avoid the expense of a cheap field for black schools if they’re allowed to use the new stadium, too, an official says. That will work, he tells the board, if the new stadium is ‘erected away from the center of the population’ of white Tyler.”

This recommendation was carried out. The project, now known as CHRISTUS Trinity Mother Frances Rose Stadium, was built directly adjacent to Butler College, a Black college located at the corner of South Lyons Avenue and Bellwood Road.

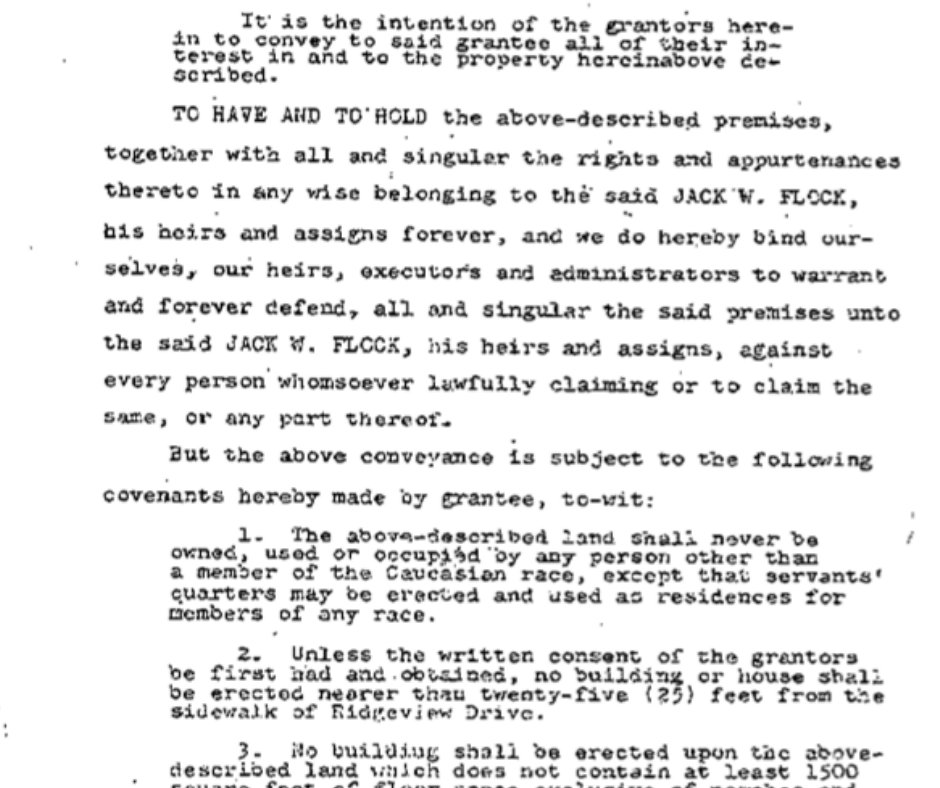

In addition to segregation by coercive city plans, private restrictive covenants from developers continued to be created and enforced. Such racist restrictive covenants were commonplace in Tyler, not only from at least the beginning of the 20th century, but throughout the 1940s and 50s.

For example, a 1949 deed from the sale of a plot of land on Edgewood Dr., just south of TJC, states that the land “shall never be owned, used, or occupied by any person other than a member of the Caucasian race, except that servants’ quarters may be erected and used as residences for members of any race.”

Another example is shown through a high profile local story this summer: the discovery by an Azalea Historic District resident that the 1959 deed to her house contains such a racist covenant. “No lot shall be sold to or occupied by any person of African blood or descent,” the deed reads, “provided, however, that this shall not prohibit the occupancy of any servant house by servants of African descent or blood.”

Also in 1959, despite the Brown v. Board ruling five years earlier declaring the racial segregation of public schools unconstitutional, “TISD open[ed] a new addition at all-black Emmett Scott High School and the new campus for all-white Robert E. Lee High School,” renewing Tyler’s commitment to housing and neighborhood segregation.

In 1968, Congress passed the Fair Housing Act, which prohibits discrimination in housing because of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status and disability. However, this legislation came far too late for Black Tylerites.

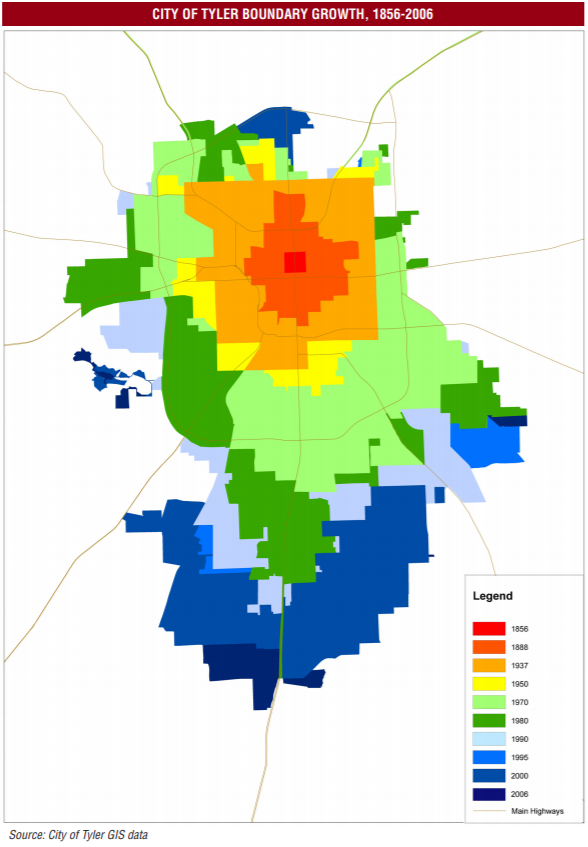

Thus, by 1970, Tyler was largely racially segregated. According to the Tyler 21 city plan, Black people “lived northwest and east of downtown and in the neighborhoods of St. Louis and Butler College in West Tyler,” and most white people lived in the southern half and the northeast corner. Though by 1950 the city had grown outward fairly equally in all directions from the courthouse square, during the mid 60s through the 70s, large numbers of white Tylerites moved south and southeast away from Tyler’s historic core.

This white flight was largely propelled by racist fears coming from the civil rights movement of the 1960s and the forced integration of Tyler schools in 1970. White Tylerites had most of the money, so the money and services followed them south. The result is that, “Despite the persistence of some stable neighborhoods, over nearly 30 years the North End and West Tyler were challenged by population decline and disinvestment while new residential and commercial development focused on growing south.”

As Tyler expanded its borders south in the late 1960s and 1970s to follow white money, it formally annexed a historically Black farming community named St. Louis which had been founded around 1880. By the time Tyler annexed St. Louis in 1973 to form its southwestern portion, the old freedmen’s colony included “the St. Louis School, two cemeteries, a church, and a sizable residential district stretching southeastward from Walton Road past Noonday Road.”

According to Darryl Bowdre, a Tyler minister, journalist and community leader who served three terms as a member of the Tyler city council, around this time there existed another Black settlement in the way of white Tyler’s southern expansion. This community was named Rosedale, and its residents lived on the land between what is now Old Jacksonville Highway and South Broadway.

The City of Tyler wanted this area for new residential and business development, including that of Broadway Square Mall, so they forced the Rosedale community to move east to an area called Clayton. Clayton was the name of the land which today is between Loop 323, Paluxy Drive, and Troup Highway, and extending northeast to the area now occupied by UT Tyler.

The displaced Rosedale community grew around New Zion Baptist Church. Bowdre said that just a few years after the Rosedale community’s initial forced removal, part of the community found itself again forced to move by the city of Tyler. This time, the reason was that the city wanted to use the land to build Tyler State College, now called UT Tyler, which was founded in 1971.

During the final decades of the 20th century and especially after 2000, many immigrants from Latin America, mainly Mexico, settled in Tyler, largely in the north and northeast sections.

Well into the 21st century, the racism of our city’s past perpetuates staggering inequality largely along racial lines. Tyler’s white flight which started in the late 1960s and early 1970s continued rapidly through 2000, and today there is no sign of it stopping. The majority of new housing and commercial developments are in the areas settled by whites during the second half of the 20th century and are encroaching still further south into the areas surrounding Loop 49 and Flint.

In their latest city plan, dubbed Tyler 21, announced in 2006 and currently underway, the city delineates north Tyler as a specific planning area. Interestingly, the borders of the North End Planning Area are precisely what have been drawn for Black Tylerites, and are the areas from which white Tylerites have fled in the last half century.

Consistent with how the city was planned, “Two-thirds of the city’s African-American population and over half of the city’s Hispanic population live in the planning area.”

The legacy of racist city planning and housing discrimination has of course, not only resulted in a segregated Tyler today, but also harrowing wealth inequality, much of which is based in housing.

In fact, according Tyler 21 city plan describing north Tyler, “Nearly 70% of the housing units [in north Tyler] were built before 1970 and one-quarter were built before 1950, in contrast to the city as whole, where only 48% were built before 1970.” And not coincidentally, “Two-thirds of persons living in poverty in Tyler live in the North End planning area, as well as 82% of all children under 18 living in poverty.”

Poverty is often racially defined and can create grueling conditions to find affordable housing in Smith County. Options are so few and the demand for affordable housing so great that a Tylerite experiencing homelessness was told by the Tyler Neighborhood Services Department in September 2019 that they hadn’t accepted an application since 2014, five years prior. At the time that I write this, the list is still closed.

The Tyler 21 plan also states that the north side of Tyler, as a result of white flight toward the south, “has experienced little housing or business investment compared to other parts of the city.” Because of this, there are “relatively few retail and service businesses in North Tyler and very few national chain businesses.”

In fact, this, too, is in large part because our city’s history of white flight and institutional racism. The Tyler 21 plan states, “North Tyler’s approximately 6,700 households today fall short of the 10,000 households that investors generally expect to support a community shopping center.” Additionally, “The median household income is only 70-75% of the 100% of the median income that, for example, chain restaurants look for to locate a new restaurant.”

On top of that, Tylerites of color continue to be the victims of predatory high cost mortgage lending. A recent study from the National Bureau of Economic Research which “examines racial and ethnic differences in high cost mortgage lending in seven diverse metropolitan areas from 2004-2007” finds that “race alone accounted for nearly all of the disparity in high-cost mortgage lending between whites and minorities.”

The study additionally finds that, “while the discrepancies between whites and minorities varied in size around the country, they were present everywhere.”

In response to these very real crises facing marginalized Tylerites, the city doesn’t aim to provide reparations to the actual communities on the north side, even though racism manifests itself in their homes, neighborhoods, and access to resources. The city, instead, calls for the gentrification of north Tyler.

The current city plan states exactly how the city intends to respond to the injustice. “A longer-term plan should focus on getting at least 10,000 households in the North Tyler area and raising the median income to at least 80% of the median income of the city as a whole. Building new housing units and attracting new residents can bring large changes in median income. Then North Tyler could attract apparel and accessories stores, general merchandise stores, and some restaurants.”

The plan continues, “Although rehabilitation of existing housing is important, it is crucial to create new housing and new types of higher-density, market-rate housing such as townhouses and multi-family units. The intent is that these units would attract households whose incomes would help bring up the overall median income of the area. This new housing development is not intended to be subsidized housing.”

If the city follows through on this plan, the nationwide, systemic violence of gentrification will be enacted locally. Tyler’s plan is not to give support to the historic residents of the north side who have been forced there by segregation, but rather to entice new residents to bring new money into the neighborhood, potentially pricing out the current residents and resulting in a loss of community culture.

The water from the tap is brown and has been for years

Amori Mitchell’s house has brown water. Mitchell, a Tyler resident, lives off of Front Street in between Harvey Hall and Mattie Jones Elementary School. “When you put a white cup under there, the water is brown,” she says. It’s not new: Mitchell says she has “been having brown water on and off for at least the last five to seven years.” And it’s not just her house; it’s the whole neighborhood.

“The neighbors buy the water filters and filter it out, or they do like I do and buy gallons of water to cook with, and bottles of water to brush our teeth and stuff with. I’ll run the water at least 10-15 minutes before I can eat,” Mitchell tells me. She contacted the water company after this summer’s round of brown water and let them know the problem.

Not long afterward, she saw some people out in the street of her neighborhood fixing something. They told her they were fixing the issue, and to just let the water run for a few days until it gets resolved. That is all she heard, and that was in June.

Mitchell tells me that her water still has not been fixed: it is now a light brown, instead of muddy like it was when they were fixing it.

Mitchell tells me that Harvey Hall was experiencing the same issue just a couple of blocks away. Unlike her neighborhood, Harvey Hall’s brown water made the news in June.

When the news broke, according to Mitchell, Harvey Hall’s problem was immediately fixed. When Mitchell attended the City of Tyler’s annual “School is Cool” backpack giveaway at Harvey Hall on August 6th, the building’s water flowed clean.

Of the help Mitchell and her neighbors can expect for better water, she says, “When I started asking my neighbors who have been there for years, they were like, ‘Yeah, they may or may not come out.’”

When I asked Mitchell if this speaks to any greater issue in Tyler, she answered that it does. “I’m pretty sure nobody has complained about any brown water on different sides of town,” she stated. “Or being in the radius of chemicals, because the plants are away from the south Tyler area and they’re mostly over there close by minority, heavily populated African-American and Hispanic communities.”

Eviction, subsidized HUD, food and medical deserts

I also heard at length from Terry Bonner, edited here for length and clarity. Terry is a Tyler resident who is passionate about shining light on disparities in Tyler education and unjust housing practices. Here is his story in his own words.

“There is a lack of education beyond high school in the Black community. Only 6.5% of Black kids who graduate from TISD are college ready. [Tyler is] a town with low opportunities for people without degrees.

[Many young Black Tylerites] move to south Tyler and eventually implode. In south Tyler apartments, if you get evicted, you can’t get another apartment. You go on the Tyler Renter Association’s list. That leads you to go back to the hood to look for housing and horrible landlords that Tyler lets run amuck. You got people paying $850 rent on houses without modern amenities, for houses that don’t even have central heating and air. Houses with roaches.

Project housing, [it] helps slumlords out the most. They evict you, put you in a slum house, and then want to evict you or kick you out or give you a notice to vacate when you get to complaining about conditions.

Housing subjects women of color to horrible conditions. They can’t focus on jobs because they’ll lose their housing. The daddy can’t move in because they’ll lose their housing. The excessive amount of rent that is being charged for public housing, they need to put a cap on it. Black people are thrown away, by and large, in rent situations. We represent most of the people going to eviction courts.

People of color who do have degrees [are allowed] to be gatekeepers in certain ways. A lot of them abuse their own people because they happen to have a degree that we don’t.

What I’m sayin’ is, we can’t look to our local leaders to help us because they’re in the pocket of those who wish to oppress us. I dare you right now to go to these [subsidized HUD] apartment complexes and try to register anybody to vote. They’ll kick you off the property, try to criminally trespass you for helping the residents to register to vote!

You see where all the project housing is being moved to, right? The north. Liberty Arms Apartments, Texas College Apartments, [Pinnacle on Broadway] all those places … [they put these housing projects in food deserts .] Ain’t no grocery stores around there. And they’re in medical care deserts. I bet you they ain’t too far from a Family Dollar or Dollar General.

Let’s not get off of predatory lending. Those adjustable rate mortgages that came through some years ago, you know who they affected the most in this town? Black people. Because that’s who this town has allowed to get them. And guess what? Who got evicted at high rates? And lost their houses at high rates? Black people. For lack of education and then being taken advantage of.

Certain parts of town only get developed when white people move in over there. Like the west right now is being gentrified. Look what’s happening over there on Earl Campbell. Pretty soon they’re going to cross over Earl Campbell and come up into what we call White City and Butler College.

See Tyler, does not ever have to call you a n_____ because they keep it written all over the walls. That’s why we want these schools done away with. Robert E. Lee, John Tyler — that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Hogg, Hubbard, you get what I’m saying — all the way to Jeff Davis Blvd., Jeb Stuart Blvd.; go over there to Oakwood Cemetery. They got a statue over there saying, ‘The Confederacy gave us the best kind of soldier, 1861-1865.’

They talk about how they try to give [HUD-subsidized affordable housing], but they don’t even keep the list open. Palestine’s not like that. Even Gladewater ain’t like that. But Tyler is.

This summer, I fell on some hard times… because my kids are at home, and seeing as they’re at home, they eat more, right? And for real I started getting broke buying food. I needed some help on my lights, and I needed some help on my rent. Now I eventually got help on my rent, but it took (a very long time).

Now for my lights, you’ve heard what Tyler touts: They’ve got all this help, all this assistance that they can give people. I’m a working father, and I share children, right? So in order for me to get help, I have to provide a birth certificate for everybody in the house, social security card for everybody in the house, two forms of ID for everybody in the house just to even be considered for help. If your lights are off, you’re going to have to wait.

You wind up trying to break your back trying to improve a property that you are renting, just so you ain’t gotta say nothing to the landlord. They say that it’s your fault. But it’s not your fault that your house is infested with roaches.

A lot of these houses ain’t even up to code. I’ve rented in houses that don’t even have a smoke detector or a fire extinguisher. That’s why you have people staying in hotels. People live in rooms for months and years at a time. They’re evicting people during this COVID stuff. Tyler, Texas don’t care, man, and I’m not just saying that to be salacious. Actions speak louder than words!”

A vision of what Tyler could be

As the heat of the East Texas summer passes into a chilly and colorful fall and election day just a week away, the residents and communities of Tyler will decide whether the robust momentum for racial justice that took our nation this summer will perpetuate — or sputter out in our local political and cultural institutions.

Will we let our racist legacy in Tyler’s housing situation continue? Will our city perpetuate the silence around racism’s central role in determining how Tylerites live? Will our city allow the median Black-owned home’s worth to be half that of whites’ when housing forms the basis of U.S. American wealth?

Will brown water, food deserts, and lack of healthcare facilities be the norm for north Tyler communities? Will Black and brown Tylerites continue to suffer because of our city’s racist layout?

Consider a Tyler where a Black-lead multiracial movement continues sweeping the city, ending with reparations for these old injustices. Black community leaders have been working to organize multiracial direct action, community meetings on race, and broadly sustained social justice movements in East Texas.

Will there be affordable health care centers in accessible spots in the north? Will healthy, affordable food options be provided to those who do not already have access? Will affordable housing be expanded for those who need it, and renters’ rights be protected?

Will historically redlined communities be offered protection from gentrification and displacement? Will Black Tylerites be given access to the wealth that was stolen from them through (among many other things) enslavement and racist housing loans?

As a community of justice-loving individuals, we have the opportunity now to mobilize and fight together for these and other long-overdue reparations that are deserved in Rose City.

Addendum

Community care is important always, and especially right now. That’s why I want to share some general resources with you that might be helpful.

Housing Resources:

Get Involved in the Movement:

Local Resource Organizations:

Luke Lee is a life-long East Texan who recently graduated from the University of Texas at Austin with a degree in History. As a freelance fellow for The Tyler Loop, Luke’s interest and research focused on how racism has shaped Tyler’s houses and neighborhoods. Now a resident of Illinois, Luke volunteers with a local chapter of SURJ (Showing Up for Racial Justice) as an election defender. SURJ is “a multi-racial movement to undermine white support for white supremacy and to help build a racially just society.”

Thanks for reading this story. Just one more thing. If you believe in the power of local journalism here in Tyler, I'm hoping that you'll help us take The Loop to the next level.

Our readers have told us what they want to better understand about this place we all call home, from Tyler's north-south divide to our city's changing demographics. Power, leadership, and who gets a seat at the table. How Tyler is growing and changing, and how we can all help it improve. Local arts, culture, entertainment, and food.

We can't do this alone. If you believe in a more informed, more connected, more engaged Tyler, help us tell the stories that need to be told in our community. Get free access to select Loop events, behind-the-scenes updates about the impact and goals of our work, and, above all, a chance to play a part in bringing more fresh, in-depth, unexpected journalism to Tyler.